46 Evaluating for Credibility

Robin Jeffrey; Christina Frasier; and Teaching & Learning, University Libraries

Learning Objectives

- Understand whether a source’s author can address a topic with authority.

- Identify strategies for assessing a source’s credibility.

Next, you’ll be evaluating each of the sources that you deemed relevant.

What are the clues for inferring a source’s credibility? The focus of this section is on evaluating online, since we all do so much of our research online. However, much of the same critical thinking skills you use to evaluate online sources can be used for books, too.

And remember, the more you take these steps, the faster it goes because always examining your sources becomes second nature.

Factors to Consider

Evaluating a website for credibility means considering the five factors below in relation to your purpose for the information. These factors are what you should gather clues about and use to decide whether a site is right for your purpose.

- The source’s context on the web.

- Author and/or publisher’s background.

- The degree of bias.

- Recognition from others.

- Thoroughness of the content.

How many factors you consider at any one time depends on your purpose when seeking information. In other words, you’ll consider all five factors when you’re looking for information for a research project or other high-stakes situation where making mistakes have serious consequences. But you might consider only the first three factors at other times.

The source’s context on the web

The context of your source can help you determine whether or not it is credible. On a website, check pages labeled About Us, About This Site, Mission, Site Index, and Site Map, if available. (If such pages or similarly labeled ones don’t exist, it may be a sign that the site may be less trustworthy.)

Ask yourself these questions to gather clues that will help you decide the source’s context:

- Is the site selling products and/or services (even if there are articles and other useful information, too)? Perhaps it’s a retail, service center, or corporate site.

- Are there membership applications and requests for contributions of money or time anywhere on the site? They’re usually a sign that you’re on a site that promotes particular ideas or behavior – in other words, they’re an advocacy site.

- Do postings, articles, reports, and/or policy papers give a one-sided view or multiple views on issues, people, and events? If they’re one-sided, the site is probably a commercial site or an advocacy group. If the information is even-handed and includes different sides of an issue, the site is more likely to be on the library/museum, school, or mainline U.S. news. Sites there usually provide information designed to educate rather than persuade. Newspapers online or in print usually do have editorial pages, however. But labeling opinions as such helps keep mainline U.S. news sources credible.

Author

If they’re available, first take a look at pages called such things as About This Site, About Us, or Our Team first. But you may need to browse around a site further to determine its author. Look for a link labeled with anything that seems like it would lead you to the author. Other sources, like books, usually have a few sentences about the author on the back cover or on the flap inside the back cover.

You may find the publisher’s name next to the copyright symbol, ©, at the bottom of at least some pages on a site. In books the identity of the publisher is traditionally on the back of the title page.

Sometimes it helps to look for whether a site belongs to a single person or to a reputable organization. Because many colleges and universities offer blog space to their faculty, staff, and students that uses the university’s web domain, this evaluation can require deeper analysis than just looking at the address. Personal blogs may not reflect the official views of an organization or meet the standards of formal publication.

In a similar manner, a tilde symbol (~) preceding a directory name in the site address indicates that the page is in a “personal” directory on the server and is not an official publication of that organization. For example, you could tell that Jones’ web page was not an official publication of XYZ University if his site’s address was: http://www.XYZuniversity.edu/~jones/page.html. The tilde indicates it’s just a personal web page—in the Residences, not Schools, neighborhood of the web.

Unless you find information about the author to the contrary, such blogs and sites should not automatically be considered to have as much authority as content that is officially part of the university’s site. Or you may find that the author has a good academic reputation and is using their blog or website to share resources he or she authored and even published elsewhere. That would nudge him or her toward the Schools neighborhood.

Learning what they have published before can also help you decide whether that organization or individual should be considered credible on the topic. Listed below are sources to use to look for what the organization or individual may have published and what has been published about them.

Bias

Whether or not a source is biased is a chief concern. Biased sources are those that do not give another side’s point of view or denies its existence. Students learning about bias often confuse it with argumentation. To be clear, argumentation involves opinion, but a good argument–the type we encourage your writing for formal college essays–is made more credible by acknowledging counterarguments. Weak arguments do not do so, which shows a bias. Thus, if a source reflects only one point of view, it might be biased, especially if the topic is controversial.

To determine bias, consider the context of the source. If the source is trying to sell something, it is more likely to be biased. Consider, too, whether or not the author’s other work is biased. You may also consider the sponsor of a site. The sponsor of a site is the person or organization who is footing the bill, will often be listed in the same place as the copyright date or author information. If you can’t find an explicit listing for a sponsor, double check the URL: .com indicates a commercial site, .edu an educational one, .org a nonprofit, .gov a government sponsor, .mil a military sponsor, or .net a network of sponsors. Each of these types of sponsors shows different levels of bias. Determine why the site was created and who it was meant to inform. For example, is it a website that was created to sell things, or a page hoping to persuade voters to take a side on a particular issue?

Consider also the peer-review process. Although bias does appear in some scholarly journal articles, because it is reviewed by a panel of experts, it is less likely to display bias than, say, a tweet.

Above all, consider your own inclinations!

Most of us have biases, and we can easily fool ourselves if we don’t make a conscious effort to keep our minds open to new information. Psychologists have shown over and over again that humans naturally tend to accept any information that supports what they already believe, even if the information isn’t very reliable. And humans also naturally tend to reject information that conflicts with those beliefs, even if the information is solid. These predilections are powerful. Unless we make an active effort to listen to all sides we can become trapped into believing something that isn’t so, and won’t even know it.

— A Process for Avoiding Deception, Annenberg Classroom

Probably all sources exhibit some bias, simply because it’s impossible for their authors to avoid letting their life experience and education have an effect on their decisions about what is relevant to put on the site and what to say about it.

But that kind of unavoidable bias is very different from a wholesale effort to shape the message so the site (or other source) amounts to a persuasive advertisement for something important to the author.

Even if the effort is not as strong as a wholesale effort, authors can find many—sometimes subtle—ways to shape communication until it loses its integrity. Such communication is too persuasive, meaning the author has sacrificed its value as information in order to persuade.

While sifting through all the web messages for the ones that suit your purpose, you’ll have to pay attention to both what’s on the sites and in your own mind.

That’s because one of the things that gets in the way of identifying evidence of bias on websites is our own biases. Sometimes the things that look most correct to us are the ones that play to our own biases.

Clues About Bias

Review the website or other source and look for evidence that the site exhibits more or less bias. The factors below provide some clues.

| Coverage | |

|---|---|

| Unbiased: This source’s information is not drastically different from coverage of the topic elsewhere. Information and opinion about the topic don’t seem to come out of nowhere. It doesn’t seem as though information has been shaped to fit. | Biased: Compared to what you’ve found in other sources covering the same topic, this content seems to omit a lot of information about the topic, emphasize vastly different aspects of it, and/or contain stereotypes or overly simplified information. Everything seems to fit the site’s theme, even though you know there are various ways to look at the issue(s). |

| Citing Sources | |

| Unbiased: The source links to any earlier news or documents it refers to. | Biased: The source refers to earlier news or documents, but does not link to the news report or document itself. |

| Evidence | |

| Unbiased: Statements are supported by evidence and documentation. | Biased: There is little evidence and documentation presented, just assertions that seem intended to persuade by themselves. |

| Vested Interest | |

| Unbiased: There is no overt evidence that the author will benefit from whichever way the topic is decided. | Biased: The author seems to have a “vested interest” in the topic. For instance, if the site asks for contributions, the author probably will benefit if contributions are made. Or, perhaps the author may get to continue his or her job if the topic that the website promotes gets decided in a particular way. |

| Imperative Language | |

| Unbiased: Statements are made without strong emphasis and without provocative twists. There aren’t many exclamation points. | Biased: There are many strongly worded assertions. There are a lot of exclamation points. |

| Multiple Viewpoints | |

| Unbiased: Both pro and con viewpoints are provided about controversial issues. | Biased: Only one version of the truth is presented about controversial issues. |

Recognition from others

Checking to see whether others have linked to a website or tagged or cited it lets you know who else on the web recognizes the value of the site’s content. Reader comments and ratings can also be informative about some sites you may be evaluating, such as blogs.

If your source is a print book, the blurbs on the front or back cover give you information from authors, experts, or other well-known people who were willing to praise the book and/or author. The same kind of “mini-reviews” may be available on the publisher’s website. You can also look for reviews of the book or other source by using Google and Google Scholar.

Those links, tags, bookmarks, citations, and positive reader comments and ratings are evidence that other authors consider the site exemplary. Book reviews, of course, may be either positive or negative.

Exactly which individuals and organizations are doing the linking, tagging, citing, rating, and commenting may also be important to you. There may be some company you’d rather your site not keep! Or, maybe the sites that link to the one you’re evaluating may help solidify your positive feelings about the site.

Don’t let an absence of links, tags, citations, ratings, and comments damn the site in your evaluation. Perhaps it’s just not well-known to other authors. The lack of them should just mean this factor can’t add any positive or negative weight to your eventual decision to use the site—it’s a neutral.

Tip: Peer Review and Citation as Recognition

The peer review most articles undergo before publication in a scholarly journal lets you know they’re considered by other scholars to be worth publishing. You might also be interested to see to what extent other researchers have used an article after it was published. (That use is what necessitates their citation.) But keep in mind that there may not be any citations for very new popular magazines, blogs, or scholarly journal articles.

What is a ‘scholarly’ or ‘peer reviewed’ source? A scholarly source is any material that has been produced by an expert in their field, reviewed by other experts in that field, and published for an audience also highly involved in that field. A source is scholarly if the following are true:

- The source is written with formal language and presented formally

- The author(s) of the source have an academic background (scientist, professor, etc.).

- The source includes a bibliography documenting the works cited in the source

- The source includes original work and analysis, rather than just summary of what’s already out there

- The source includes evidence from primary sources

- The source includes a description of the author(s) methods of research.

Clues about Recognition

Find book reviews. Jacket blurbs for popular books and review articles of scholarly books can help you decide the credibility of a book source.

Find citations of an article. Although there is no simple way to find every source that cites an article in a popular magazine, a blog, or a scholarly journal, there are some ways to look for these connections.

For articles published in popular magazines or blogs, enter the title of the article in quotes in the search box of a search engine like Google. The resulting list should show you the original article you’re evaluating, plus other sites that have mentioned it in some way. Click on those that you want to know more about.

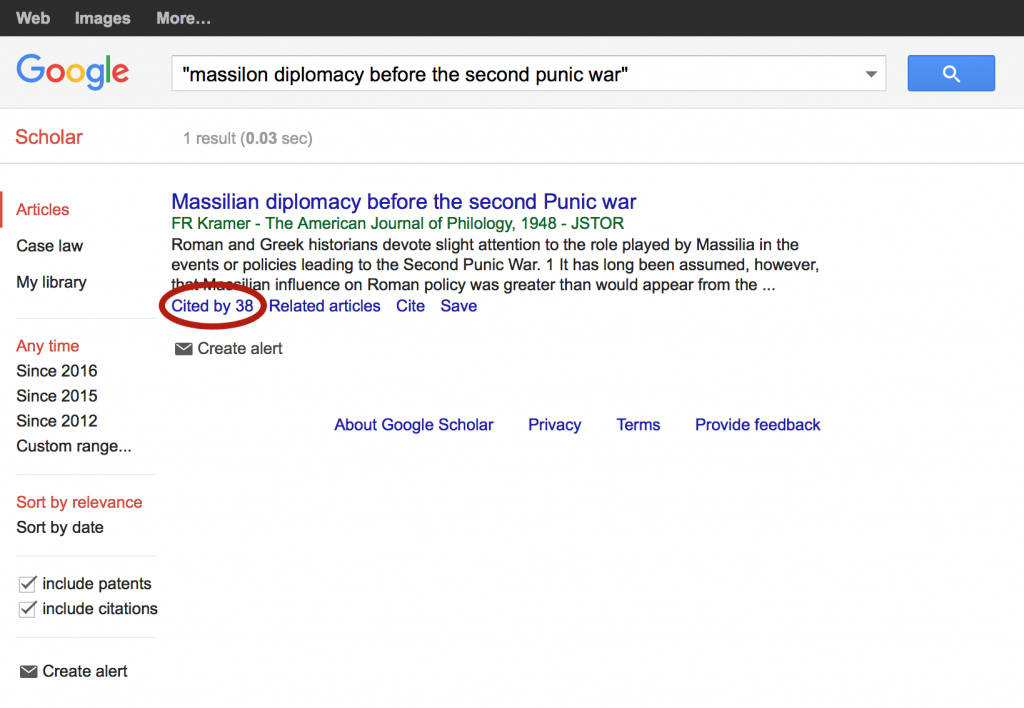

For articles published in scholarly journals, use Google Scholar to enter the title of the article in quotes. In the results list, find the article you’re evaluating. (Many articles have similar titles.) Look for the number of citations in the lower left of the listing for your article. If you want more information on the authors who have done the citing, click on the citation number for a clickable list of articles or papers and get the names of authors to look up at the end of the articles or with a search engine. (This is a good way to discover more articles about your topic, too.)

View the live example.

Th0roughness of the content

The breadth of information and depth into which the author delves to assemble information for the source is an important part of a source’s credibility. There is a substantial difference between a longform investigative news article requiring years of in-depth reporting and a blog post on the same subject; blog posts are by their nature shorter, generally, and are thus less thorough. Tweets are less thorough still.

Figuring out whether a website or other source is suitable for your purpose also means looking at how thoroughly it covers your topic.

You can evaluate thoroughness in relation to other sources on the same topic. Compare your source to how other sources cover the material, checking for missing topics or perspectives.

Clues About Thoroughness

Click around a site to get some idea of how thoroughly it covers the topic. If the source you are evaluating is a print resource, read the introduction and conclusion and also the table of contents to get a glimpse of what it covers. Look at the index to see what subject is covered with the most pages. Is it thorough enough to meet your information need?

Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research, Teaching & Learning University Libraries, CC BY 4.0

About Writing: A Guide by Robin Jeffrey, CC BY 4.0