6 Analyzing the Rhetorical Situation

Melissa Elston; Elizabeth Browning; Kirsten DeVries; Kathy Boylan; Jenifer Kurtz; and Katelyn Burton

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the components of a rhetorical situation, including the writer, the audience, and the purpose

- Recognize how context shapes other elements of the rhetorical situation

In the last chapter, you familiarized yourself with Aristotle’s means of persuasion, and how they map to our modern understandings of communication. Now, it is time to take stock of the broader context in which persuasion occurs, whether in a bank office or a college classroom. We call this broader context “the rhetorical situation.”

Analyzing any situation rhetorically means understanding the circumstances of that situation — as well as the ways in which those circumstances shape audience, purpose, and the communicator’s role in addressing things. Each rhetorical situation comprises a handful of key elements. These elements include the communicator in the situation (the writer or speaker), the issue at hand (the topic or problem being addressed), the purpose for addressing the issue, the genre and medium of delivery (e.g.–speech, written text, a commercial), and the audience being addressed.

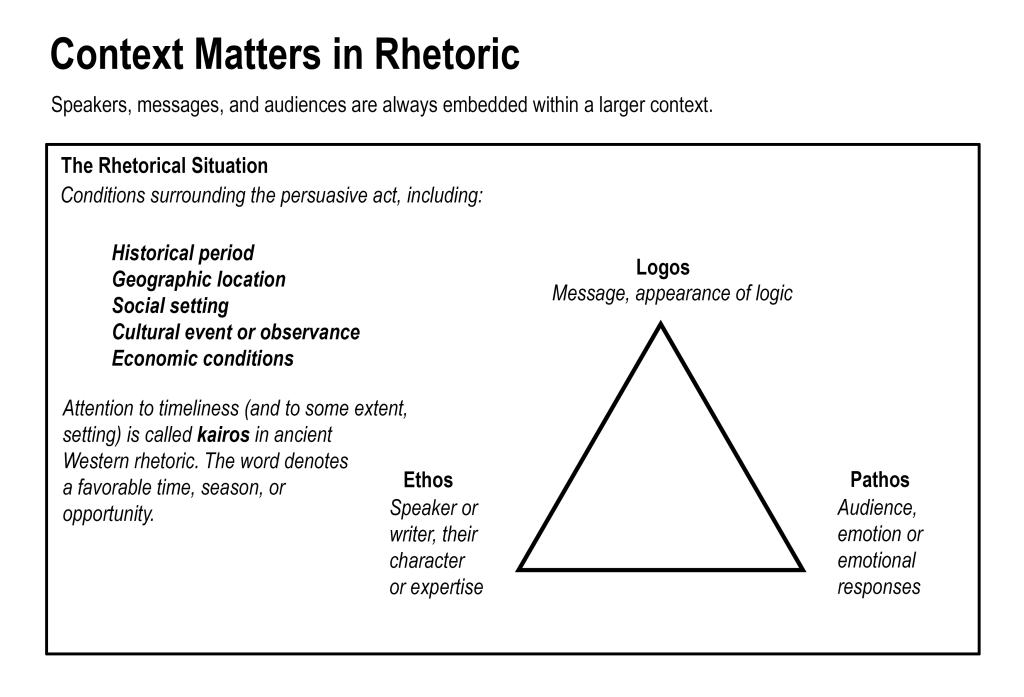

The rhetorical situation is also affected by other contextual elements, such as time, place, and occasion. Paying attention to timing was especially important to ancient Greco-Roman rhetoricians. They called the ability to “seize the moment” kairos. Alongside logos, ethos, and pathos, practicing effective kairos — in other words, recognizing an ideal opportunity or occasion to communicate — can be an additional means of boosting your message’s appeal.

The figure below illustrates the relationship between context and the other elements of a given rhetorical situation:

How to Approach the Rhetorical Situation

Now that you are familiar with both Aristotle’s appeals and the elements of the Communication Triangle, you can put them to work as you plan your papers. The following questions are adapted from the 2018 open textbook Let’s Get Writing! Answering them will help you better understand your own rhetorical situation before you begin a writing project.

-

Who is the communicator/writer?

Note: The short answer is “you.” But it is worth considering how your audience will likely view you (i.e., your ethos).

- What is your relationship to the subject matter? What qualifications or interest do you have in it?

- How do you come across in writing? Are audiences likely to find you authoritative? Trustworthy? Relatable?

-

What issue are you, the writer, addressing in your message?

- What is the main argument that you plan to make?

-

What is your purpose for addressing this issue?

- To provoke, to attack, or to defend?

- To push toward or dissuade from certain action?

- To praise or to blame?

- To teach, to delight, or to persuade?

-

Who is the audience?

- Who is the intended audience for this project?

- What values does the audience hold that you can potentially appeal to?

- Who have been or might be secondary audiences — in other words, audiences who may read the material as “onlookers” later on? (This is an important consideration, in the age of internet paper repositories.)

- If you are writing a work of fiction, what is the nature of the audience within the fiction?

-

What is your context?

- Is there an event or occasion for this piece of writing?

- What conditions (examples: historical, political, geographic, economic, etc.) surround this piece of writing? How do they shape your concerns as a writer? How are they likely to shape your audience’s concerns, beliefs, and possible response(s)?

-

What is the form in which you plan to convey your message, given this context (and audience expectations)?

- What oral or written genre do you intend to use? How is it typically arranged?

- How do you plan to adapt or alter this structure, given your goals as a writer?

- What figures of speech (schemes and tropes), if any, do you plan to use?

- What kind of style and tone do you wish to convey — and for what purpose?

- Does the writing project’s intended form complement the content?

- What effect could the form have, and does this aid or hinder your intentions?

Adapted from Let’s Get Writing! by Elizabeth Browning; Kirsten DeVries; Kathy Boylan; Jenifer Kurtz; and Katelyn Burton, CC BY-SA 4.0