Section 5.3 – Polar Coordinates

Learning Objectives

Welcome to Section 5.3! In this section, you will:

- Plot points using polar coordinates.

- Convert from polar coordinates to rectangular coordinates.

- Convert from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates.

- Transform equations between polar and rectangular forms.

- Identify and graph polar equations by converting to rectangular equations.

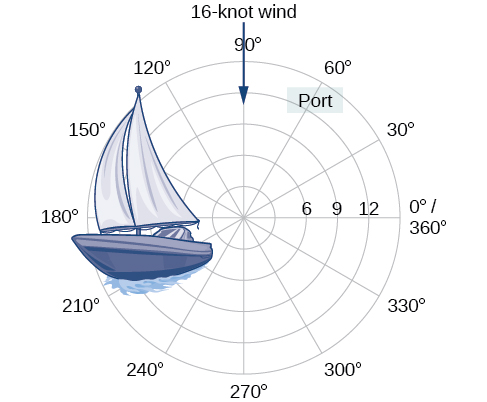

Over 12 kilometers from port, a sailboat encounters rough weather and is blown off course by a 16-knot wind (see Figure 1). How can the sailor indicate his location to the Coast Guard? In this section, we will investigate a method of representing location that is different from a standard coordinate grid.

Plotting Points Using Polar Coordinates

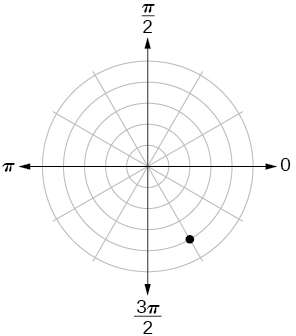

When we think about plotting points in the plane, we usually think of rectangular coordinates [latex](x,y)[/latex] in the Cartesian coordinate plane. However, there are other ways of writing a coordinate pair and other types of grid systems. In this section, we introduce to polar coordinates, which are points labeled [latex](r,θ)[/latex] and plotted on a polar grid. The polar grid is represented as a series of concentric circles radiating out from the pole, or the origin of the coordinate plane.

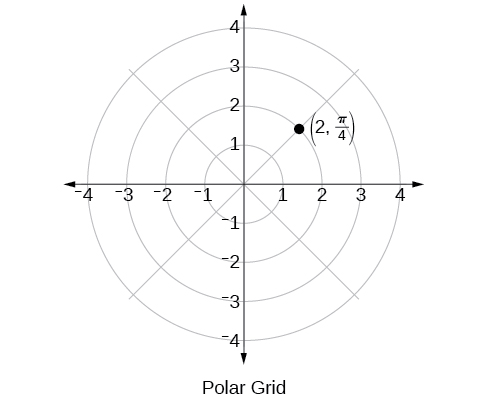

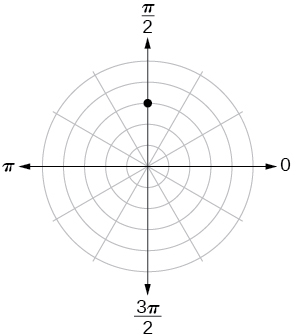

The polar grid is scaled as the unit circle with the positive x-axis now viewed as the polar axis and the origin as the pole. The first coordinate [latex]r[/latex] is the radius or length of the directed line segment from the pole. The angle [latex]θ[/latex], measured in radians, indicates the direction of [latex]r[/latex]. We move counterclockwise from the polar axis by an angle of [latex]θ[/latex], and measure a directed line segment the length of [latex]r[/latex] in the direction of [latex]θ[/latex]. Even though we measure [latex]θ[/latex] first and then [latex]r[/latex], the polar point is written with the r-coordinate first. For example, to plot the point [latex](2,\frac{π}{4})[/latex], we would move [latex]\frac{π}{4}[/latex] units in the counterclockwise direction and then a length of 2 from the pole. This point is plotted on the grid in Figure 2.

Example 1

Plotting a Point on the Polar Grid

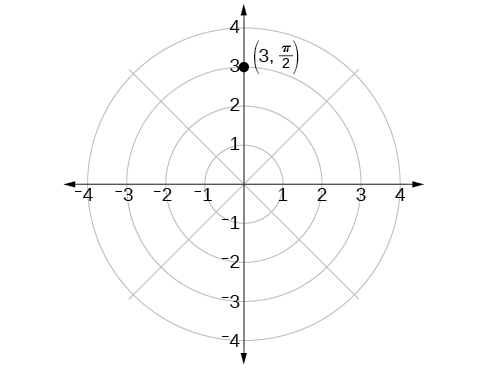

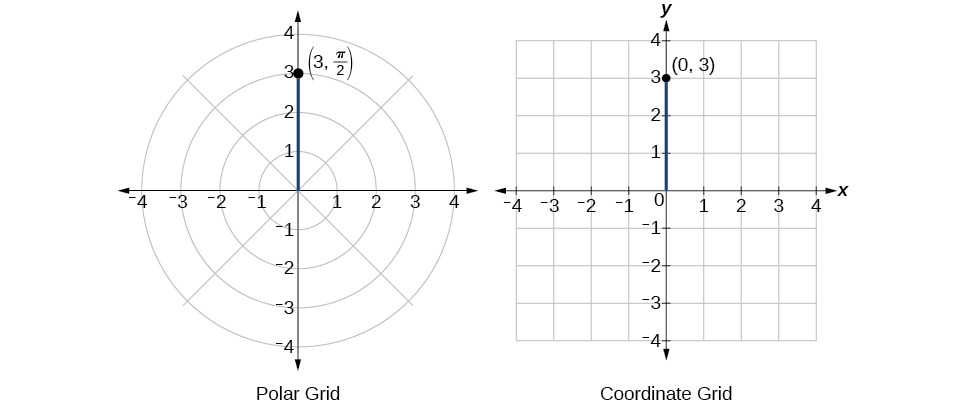

Plot the point [latex](3,\frac{π}{2})[/latex] on the polar grid.

Show/Hide Solution

The angle [latex]\frac{π}{2}[/latex] is found by sweeping in a counterclockwise direction 90° from the polar axis. The point is located at a length of 3 units from the pole in the [latex]\frac{π}{2}[/latex] direction, as shown in Figure 3.

Try It #1

Plot the point [latex](2, \frac{π}{3})[/latex] in the polar grid.

Example 2

Plotting a Point in the Polar Coordinate System with a Negative Component

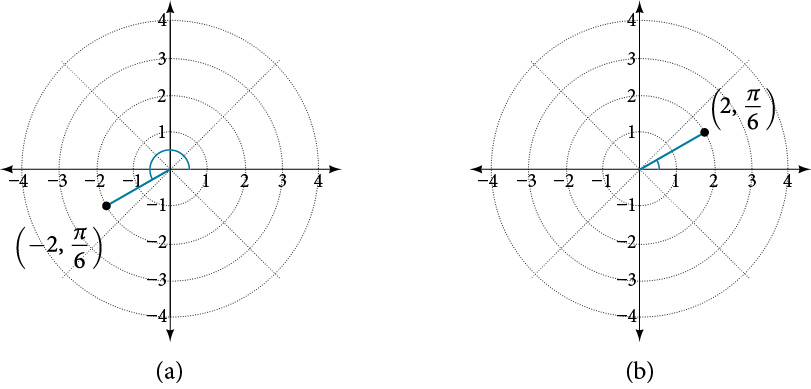

Plot the point [latex](−2, \frac{π}{6})[/latex] on the polar grid.

Show/Hide Solution

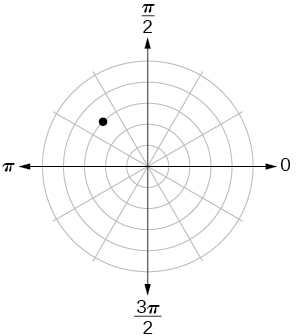

We know that [latex]\frac{π}{6}[/latex] is located in the first quadrant. However, [latex]r=−2[/latex]. We can approach plotting a point with a negative [latex]r[/latex] in two ways:

- Plot the point [latex](2,\frac{π}{6})[/latex] by moving [latex]\frac{π}{6}[/latex] in the counterclockwise direction and extending a directed line segment 2 units into the first quadrant. Then retrace the directed line segment back through the pole, and continue 2 units into the third quadrant;

- Move [latex]\frac{π}{6}[/latex] in the counterclockwise direction, and draw the directed line segment from the pole 2 units in the negative direction, into the third quadrant.

See Figure 4(a). Compare this to the graph of the polar coordinate [latex](2,\frac{π}{6})[/latex] shown in Figure 4(b).

Try It #2

Plot the points [latex](3,−\frac{π}{6})[/latex] and [latex](2,\frac{9π}{4})[/latex] on the same polar grid.

Converting from Polar Coordinates to Rectangular Coordinates

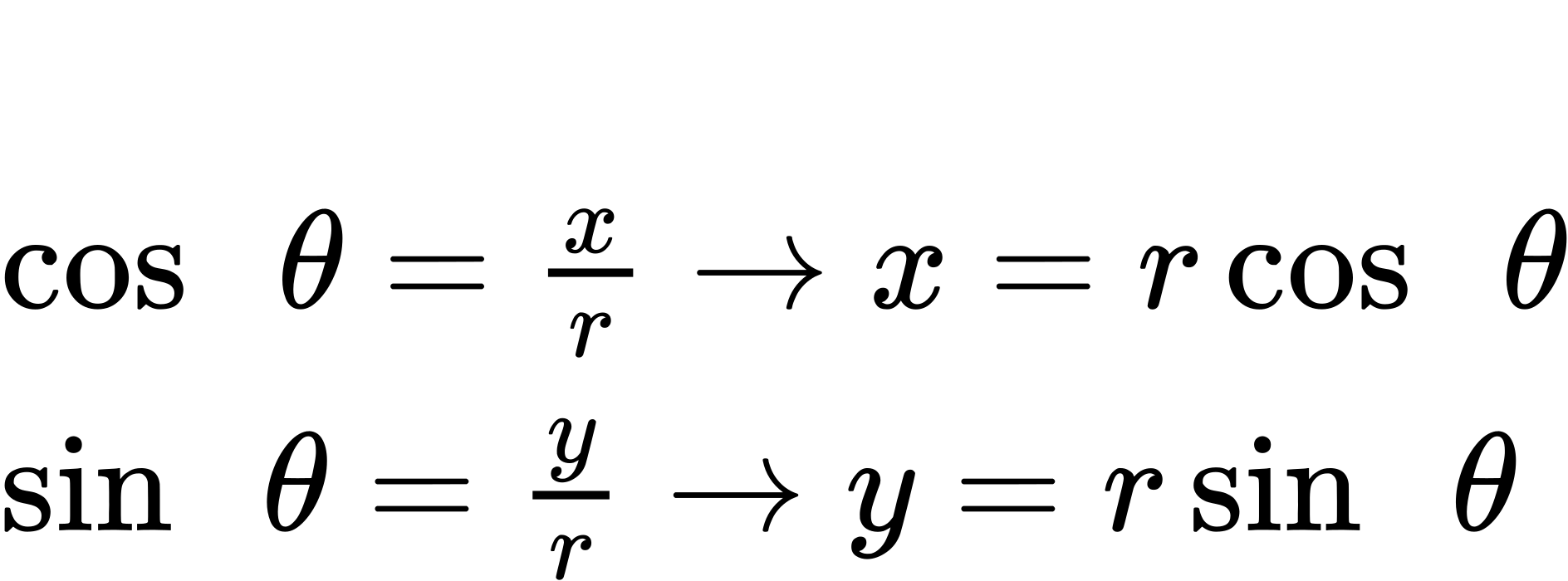

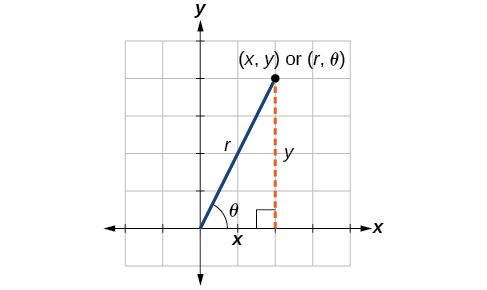

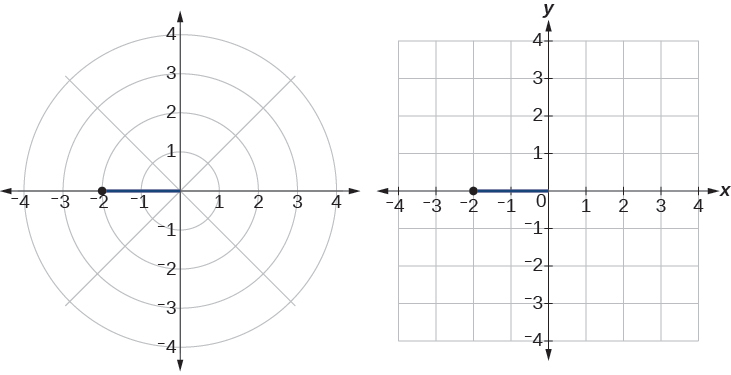

When given a set of polar coordinates, we may need to convert them to rectangular coordinates. To do so, we can recall the relationships that exist among the variables [latex]x, y, r[/latex], and [latex]θ[/latex].

Dropping a perpendicular from the point in the plane to the x-axis forms a right triangle, as illustrated in Figure 5. An easy way to remember the equations above is to think of [latex]cos θ[/latex] as the adjacent side over the hypotenuse and [latex]sin θ[/latex] as the opposite side over the hypotenuse.

Converting from Polar Coordinates to Rectangular Coordinates

To convert polar coordinates [latex](r, θ)[/latex] to rectangular coordinates [latex](x, y)[/latex], let

[latex]cos θ=\frac{x}{r}→x=rcos θ[/latex]

[latex]sin θ=\frac{y}{r}→y=rsin θ[/latex]

How To

Given polar coordinates, convert to rectangular coordinates.

- Given the polar coordinate [latex](r,θ)[/latex], write [latex]x=rcos θ[/latex] and [latex]y=rsin θ[/latex].

- Evaluate [latex]cos θ[/latex] and [latex]sin θ[/latex].

- Multiply [latex]cos θ[/latex] by [latex]r[/latex] to find the x-coordinate of the rectangular form.

- Multiply [latex]sin θ[/latex] by [latex]r[/latex] to find the y-coordinate of the rectangular form.

Example 3

Writing Polar Coordinates as Rectangular Coordinates

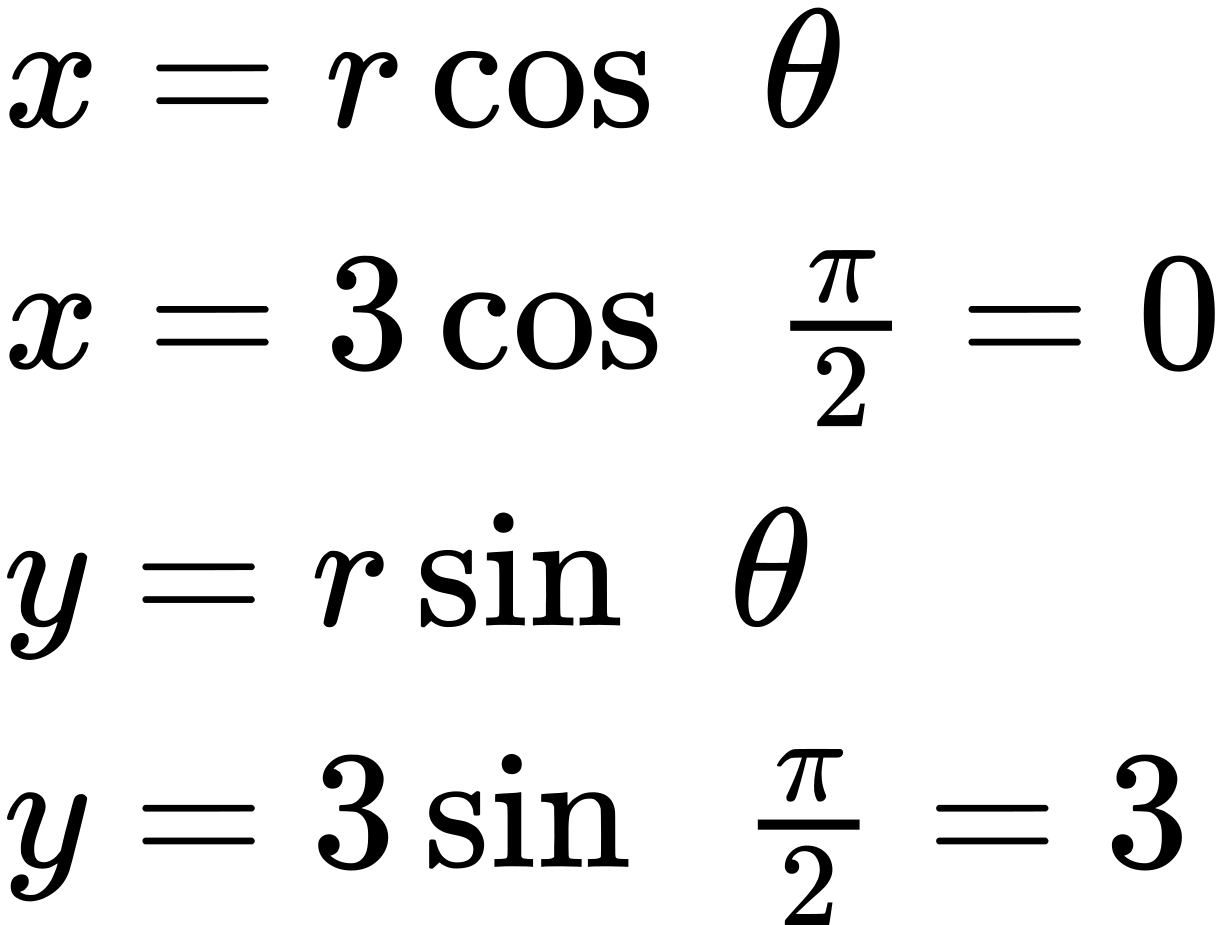

Write the polar coordinates [latex](3,\frac{π}{2})[/latex] as rectangular coordinates.

Show/Hide Solution

Use the equivalent relationships.

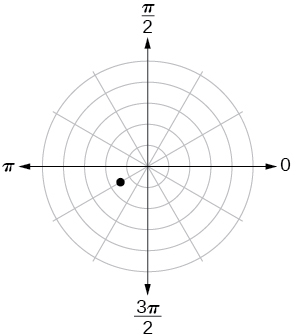

The rectangular coordinates are [latex](0,3)[/latex]. See Figure 6.

Example 4

Writing Polar Coordinates as Rectangular Coordinates

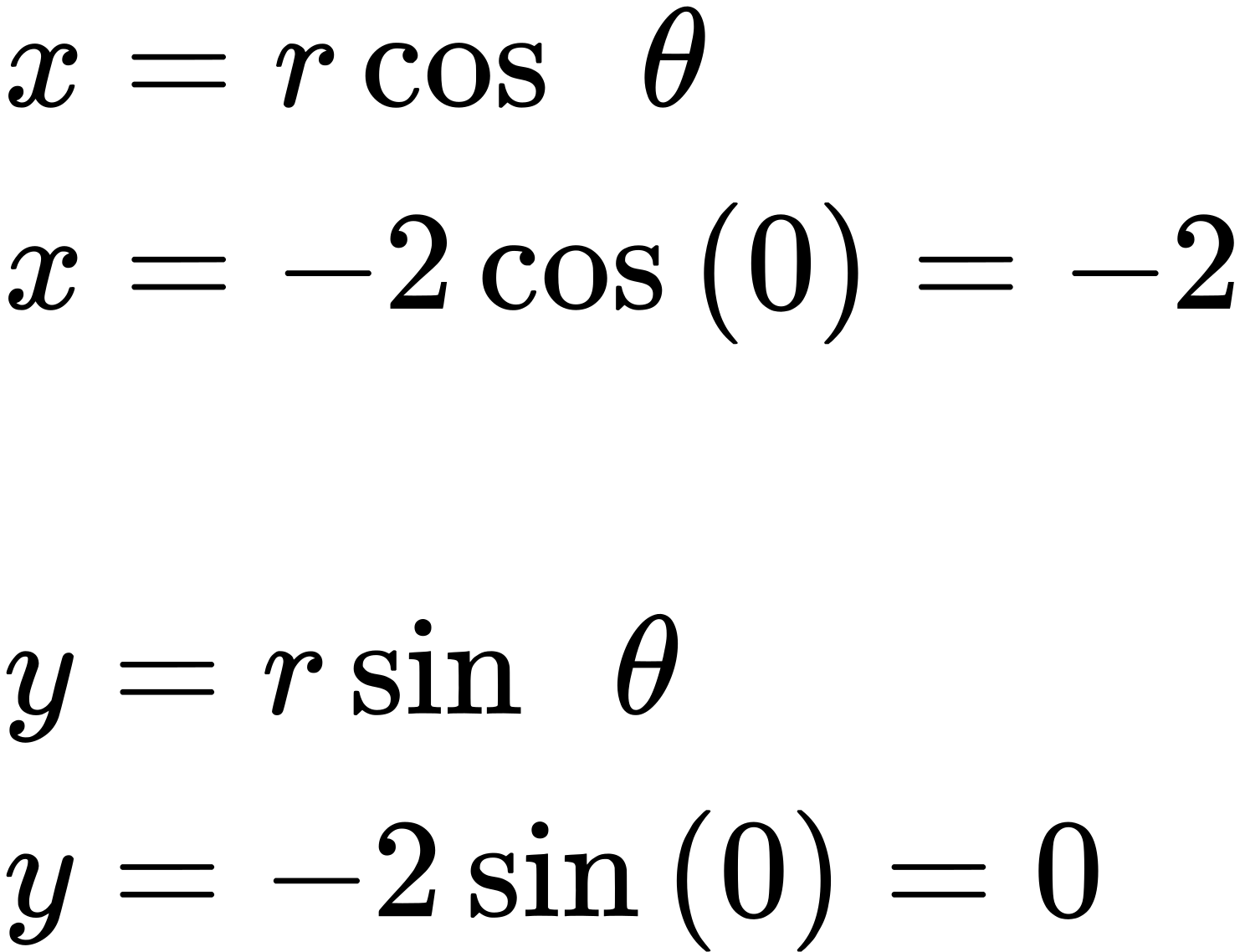

Write the polar coordinates [latex](−2,0)[/latex] as rectangular coordinates.

Show/Hide Solution

See Figure 7. Writing the polar coordinates as rectangular, we have

The rectangular coordinates are also [latex](−2,0)[/latex].

Try It #3

Write the polar coordinates [latex](−1,\frac{2π}{3})[/latex] as rectangular coordinates.

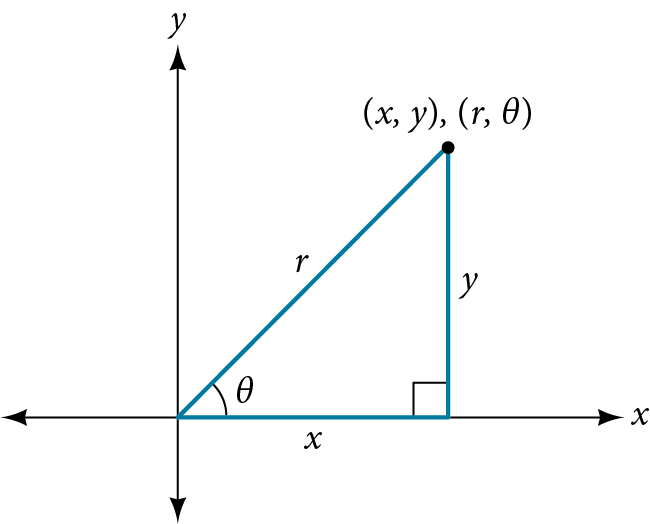

Converting from Rectangular Coordinates to Polar Coordinates

To convert rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates, we will use two other familiar relationships. With this conversion, however, we need to be aware that a set of rectangular coordinates will yield more than one polar point.

Converting from Rectangular Coordinates to Polar Coordinates

Converting from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates requires the use of one or more of the relationships illustrated in Figure 8.

Example 5

Writing Rectangular Coordinates as Polar Coordinates

Convert the rectangular coordinates [latex](3,3)[/latex] to polar coordinates.

Show/Hide Solution

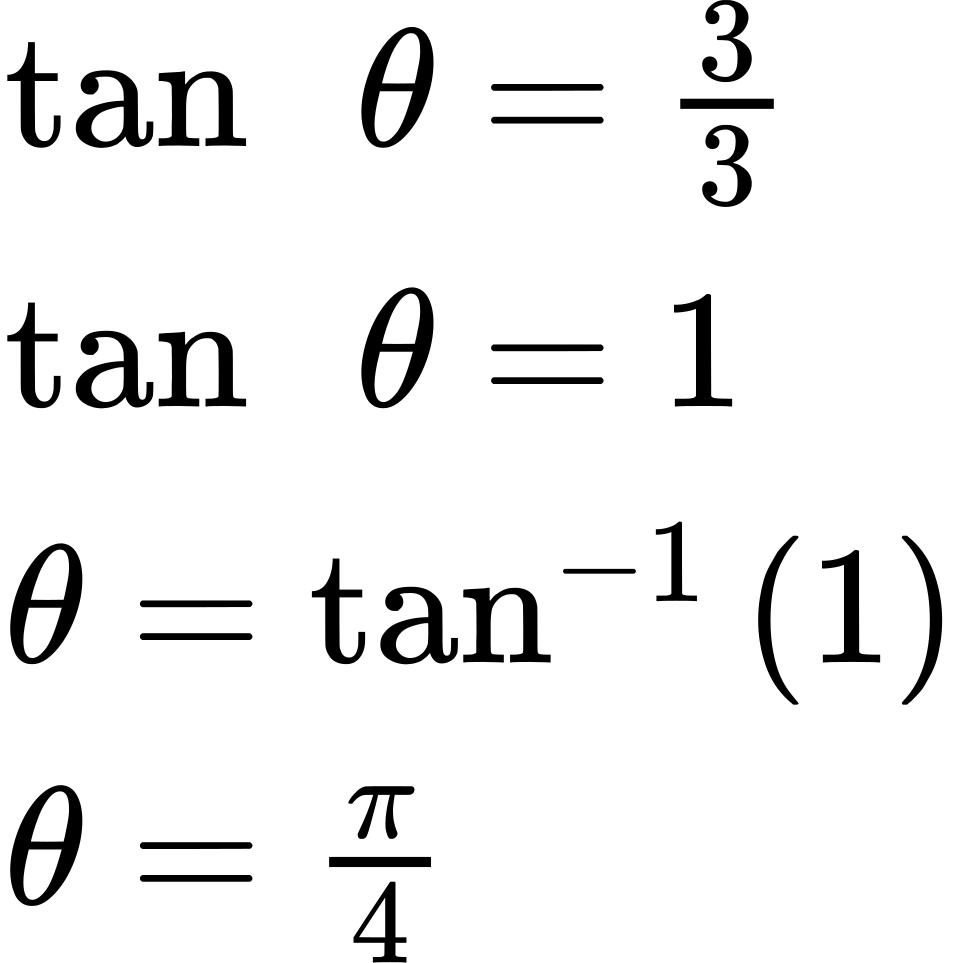

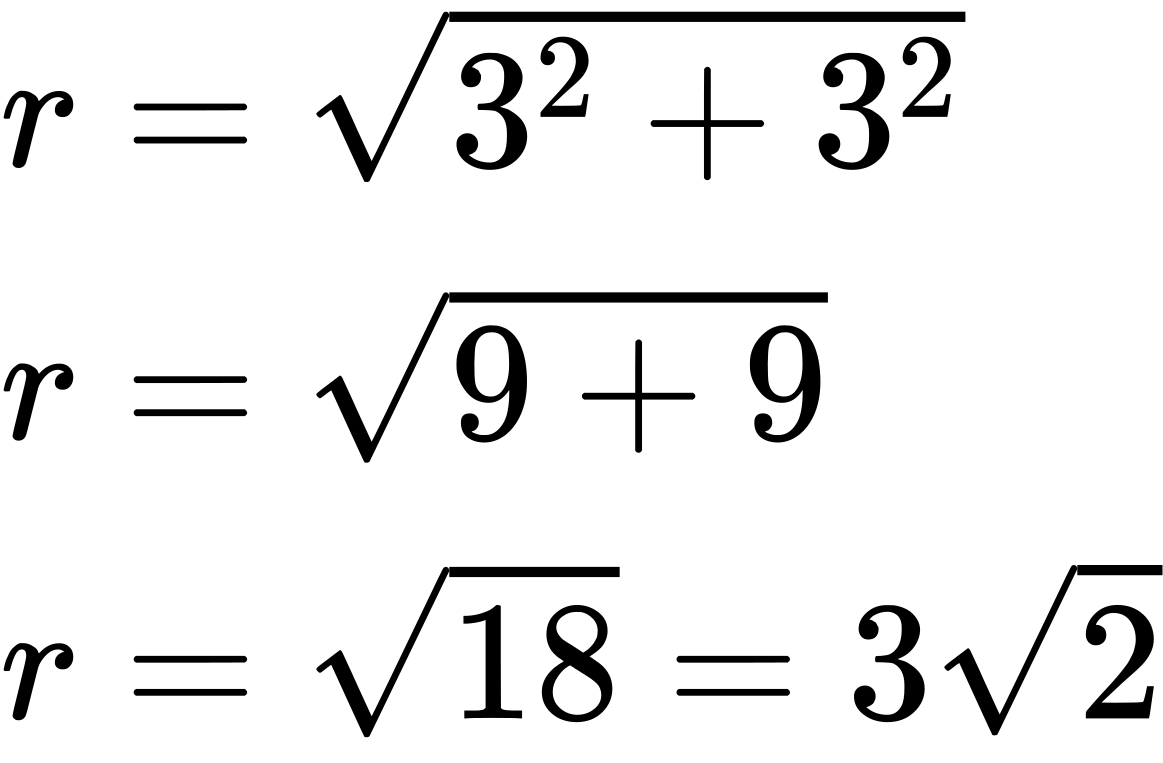

We see that the original point [latex](3,3)[/latex] is in the first quadrant. To find [latex]θ[/latex], use the formula [latex]tan θ=\frac{y}{x}[/latex]. This gives

To find [latex]r[/latex], we substitute the values for [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] into the formula [latex]r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}[/latex]. We know that [latex]r[/latex] must be positive, as [latex]\frac{π}{4}[/latex] is in the first quadrant. Thus

So, [latex]r=3\sqrt{2} [/latex] and [latex]θ=\frac{π}{4}[/latex], giving us the polar point [latex](3\sqrt{2},\frac{π}{4})[/latex]. See Figure 9.

Analysis

There are other sets of polar coordinates that will be the same as our first solution. For example, the points [latex](−3\sqrt{2}, \frac{5π}{4})[/latex] and [latex](3\sqrt{2},−\frac{7π}{4})[/latex] will coincide with the original solution of [latex](3\sqrt{2}, \frac{π}{4})[/latex]. The point [latex](−3\sqrt{2}, \frac{5π}{4})[/latex] indicates a move further counterclockwise by [latex]π[/latex], which is directly opposite [latex]\frac{π}{4}[/latex]. The radius is expressed as [latex]−3\sqrt{2}[/latex]. However, the angle [latex]\frac{5π}{4}[/latex] is located in the third quadrant and, as [latex]r[/latex] is negative, we extend the directed line segment in the opposite direction, into the first quadrant. This is the same point as [latex](3\sqrt{2}, \frac{π}{4})[/latex]. The point [latex](3\sqrt{2}, −\frac{7π}{4})[/latex] is a move further clockwise by [latex]−\frac{7π}{4}[/latex], from [latex]\frac{π}{4}[/latex]. The radius, [latex]3\sqrt{2}[/latex], is the same.

Transforming Equations between Polar and Rectangular Forms

We can now convert coordinates between polar and rectangular form. Converting equations can be more difficult, but it can be beneficial to be able to convert between the two forms. Since there are a number of polar equations that cannot be expressed clearly in Cartesian form, and vice versa, we can use the same procedures we used to convert points between the coordinate systems. We can then use a graphing calculator to graph either the rectangular form or the polar form of the equation.

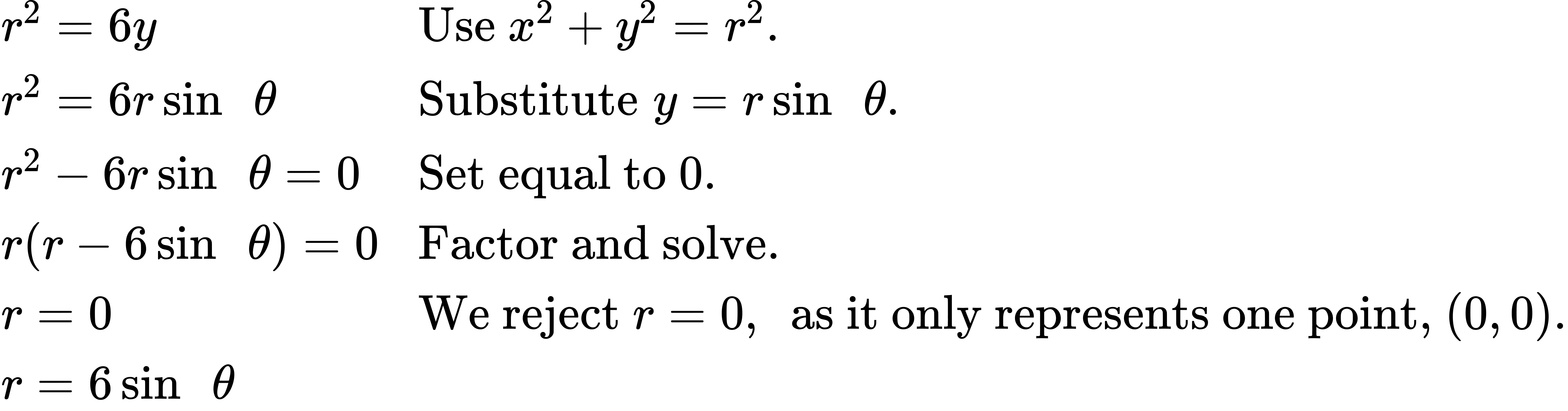

Example 6

Writing a Cartesian Equation in Polar Form

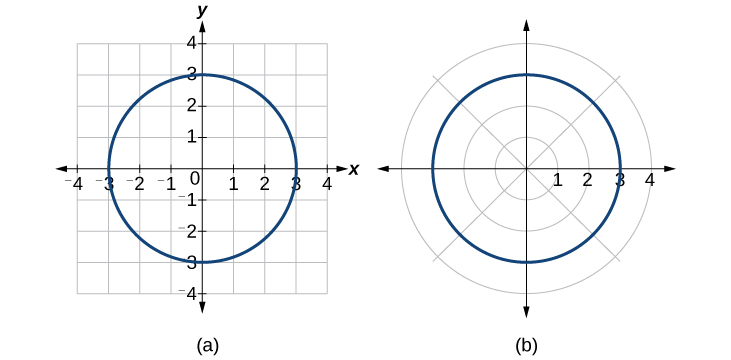

Write the Cartesian equation [latex]x^2+y^2=9[/latex] in polar form.

Show/Hide Solution

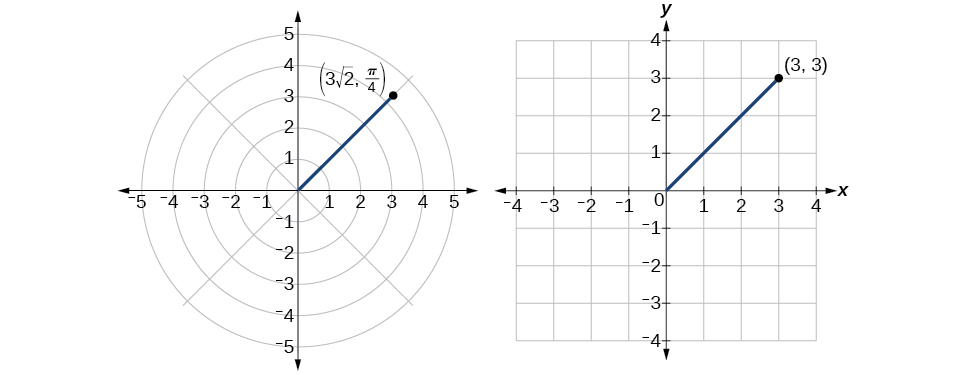

The goal is to eliminate [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex] from the equation and introduce [latex]r[/latex] and [latex]θ[/latex]. Ideally, we would write the equation [latex]r[/latex] as a function of [latex]θ[/latex]. To obtain the polar form, we will use the relationships between [latex](x,y)[/latex] and [latex](r,θ)[/latex]. Since [latex]x=rcos θ[/latex] and [latex]y=rsin θ[/latex], we can substitute and solve for [latex]r[/latex].

Thus, [latex]x^2+y^2=9,r=3[/latex], and [latex]r=−3[/latex] should generate the same graph. See Figure 10.

To graph a circle in rectangular form, we must first solve for [latex]y[/latex].

Note that this is two separate functions, since a circle fails the vertical line test. Therefore, we need to enter the positive and negative square roots into the calculator separately, as two equations in the form [latex]Y_1=\sqrt{9−x^2}[/latex] and [latex]Y_2=−\sqrt{9−x^2}[/latex]. Press GRAPH.

Example 7

Rewriting a Cartesian Equation as a Polar Equation

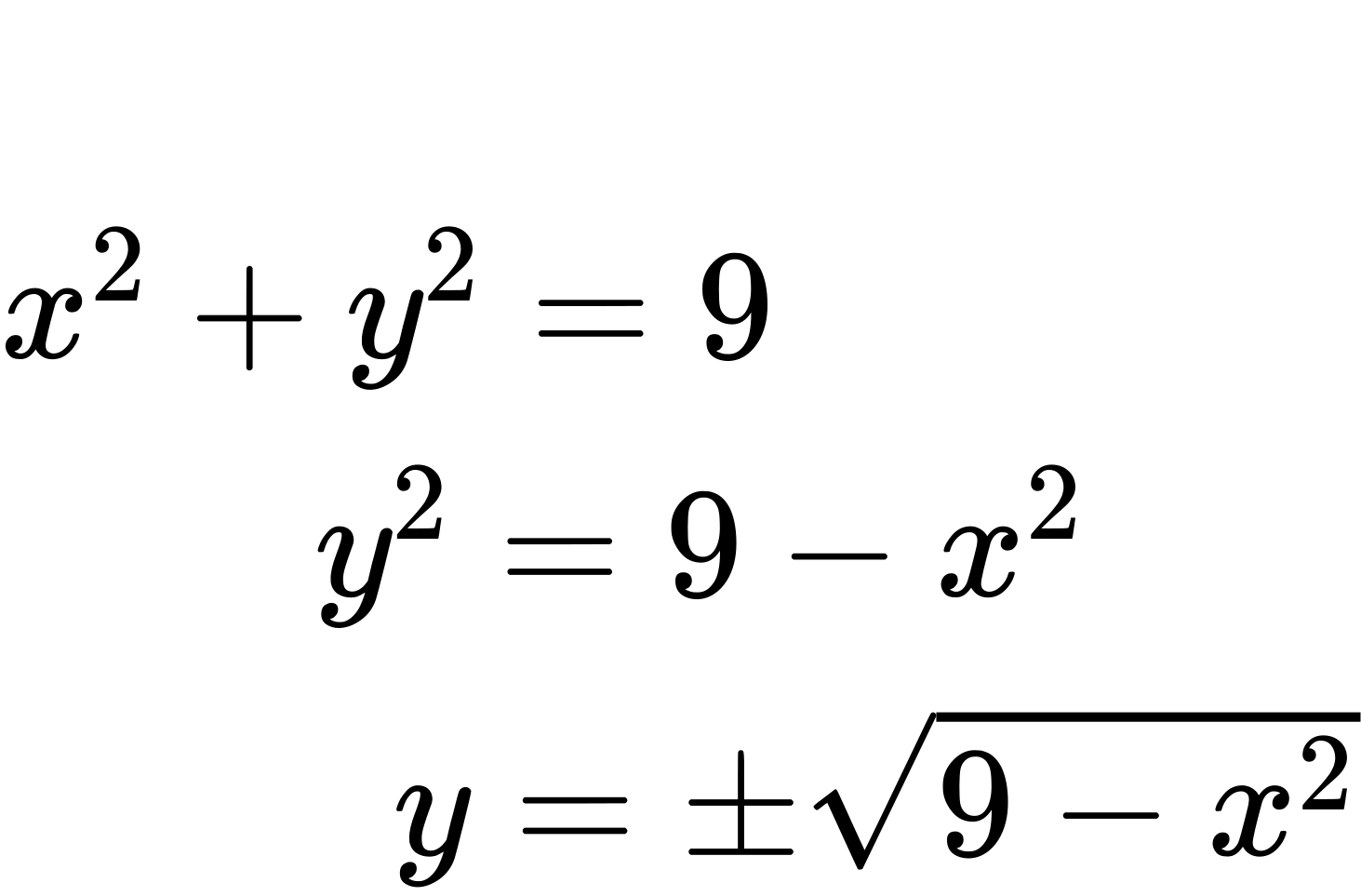

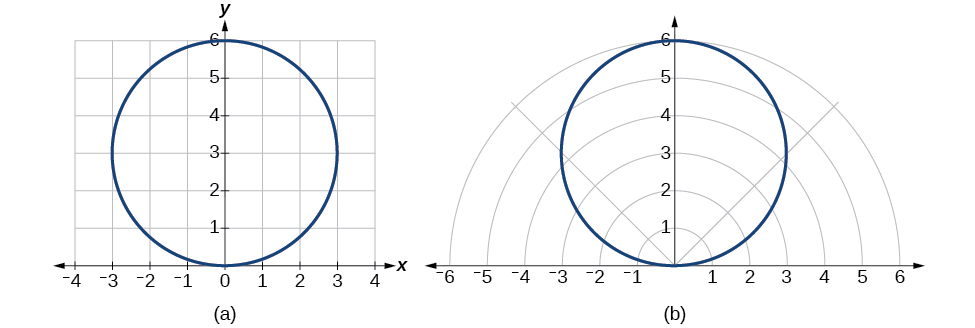

Rewrite the Cartesian equation [latex]x^2+y^2=6y[/latex] as a polar equation.

Show/Hide Solution

This equation appears similar to the previous example, but it requires different steps to convert the equation.

We can still follow the same procedures we have already learned and make the following substitutions:

Therefore, the equations [latex]x^2+y^2=6y[/latex] and [latex]r=6sin θ[/latex] should give us the same graph. See Figure 11.

The Cartesian or rectangular equation is plotted on the rectangular grid, and the polar equation is plotted on the polar grid. Clearly, the graphs are identical.

Example 8

Rewriting a Cartesian Equation in Polar Form

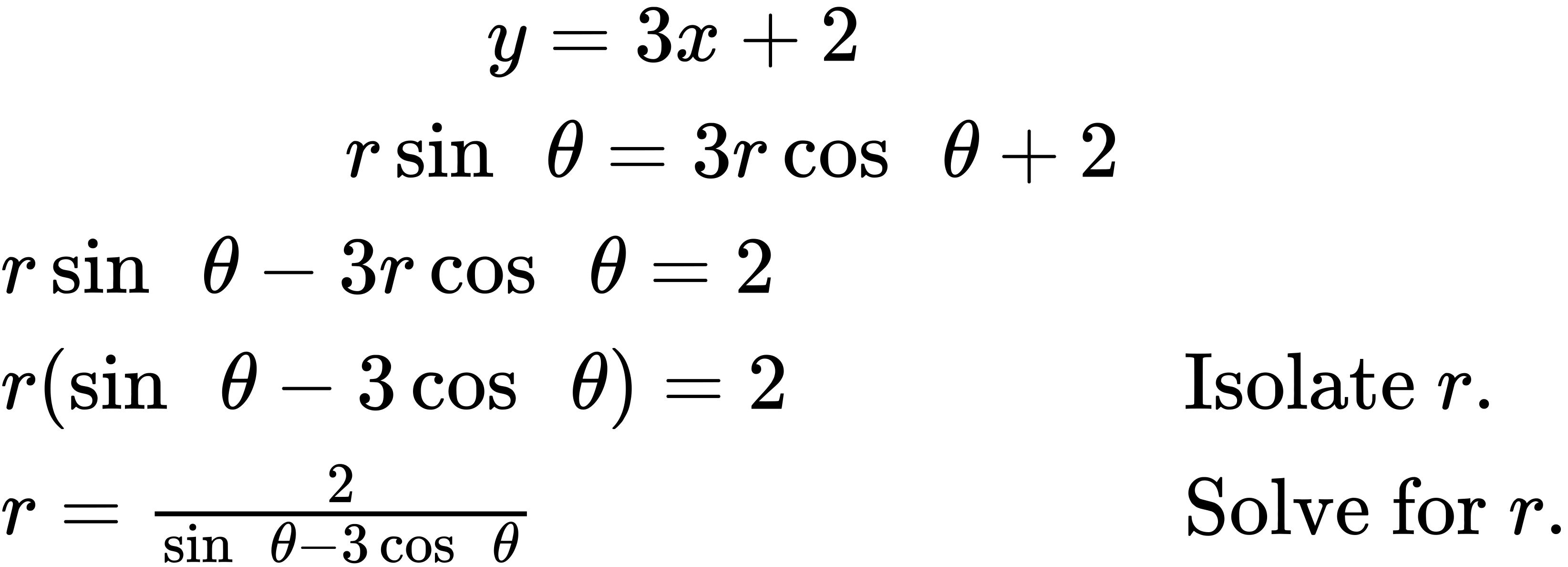

Rewrite the Cartesian equation [latex]y=3x+2[/latex] as a polar equation.

Show/Hide Solution

We will use the relationships [latex]x=rcos θ[/latex] and [latex]y=rsin θ[/latex].

Try It #4

Rewrite the Cartesian equation [latex]y^2=3−x^2[/latex] in polar form.

Identify and Graph Polar Equations by Converting to Rectangular Equations

We have learned how to convert rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates, and we have seen that the points are indeed the same. We have also transformed polar equations to rectangular equations and vice versa. Now we will demonstrate that their graphs, while drawn on different grids, are identical.

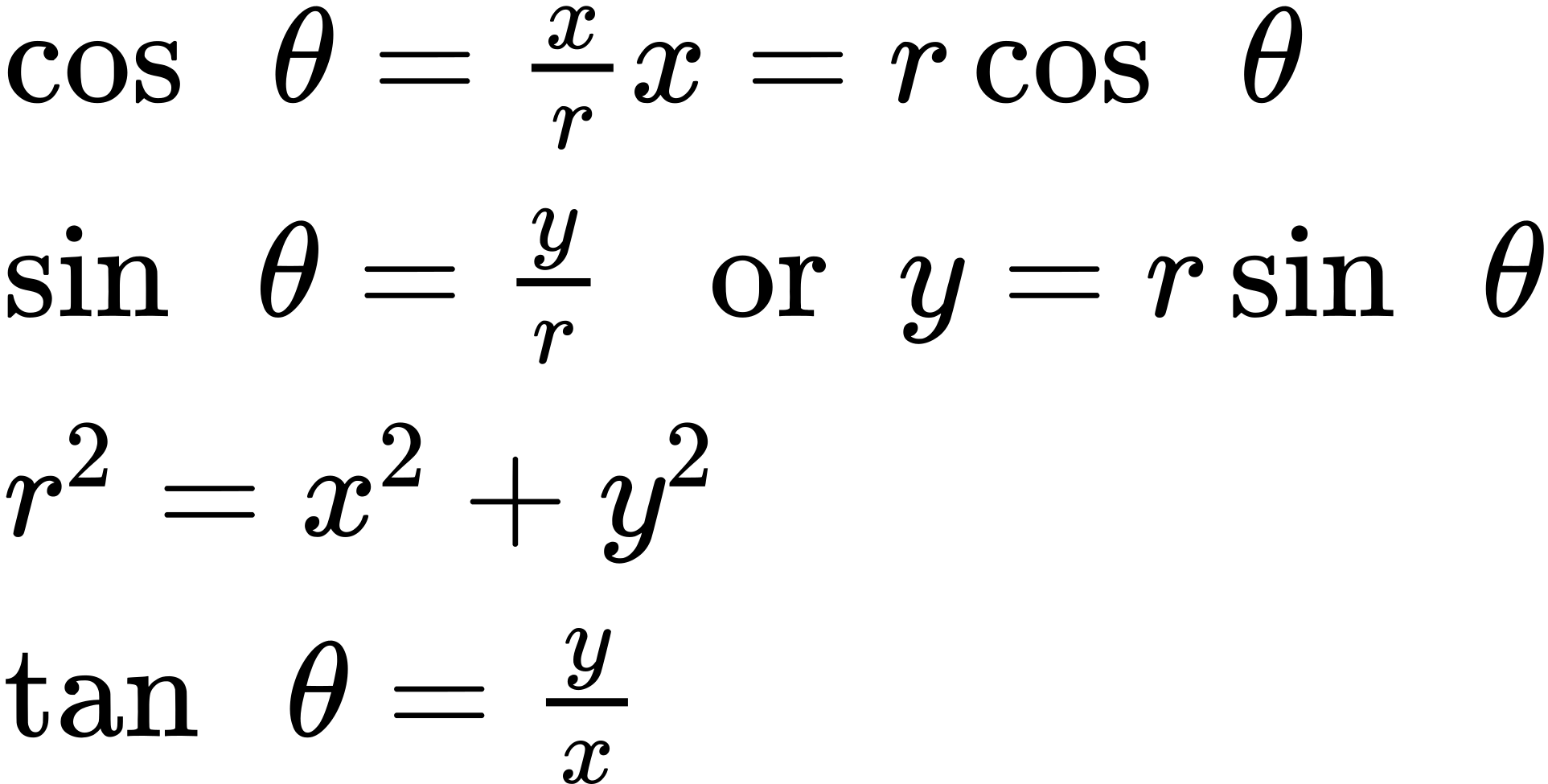

Example 9

Graphing a Polar Equation by Converting to a Rectangular Equation

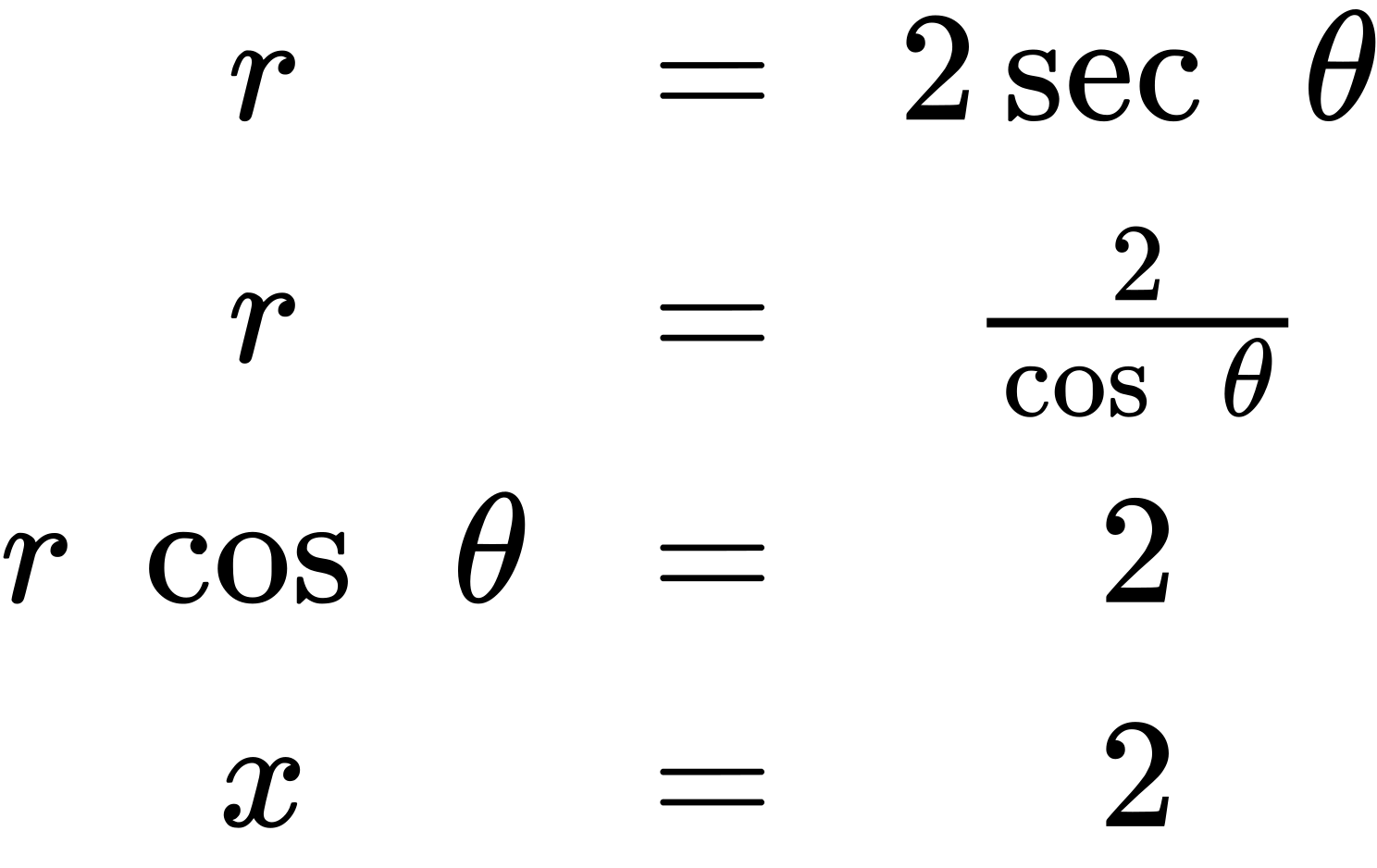

Covert the polar equation [latex]r=2sec θ[/latex] to a rectangular equation, and draw its corresponding graph.

Show/Hide Solution

The conversion is

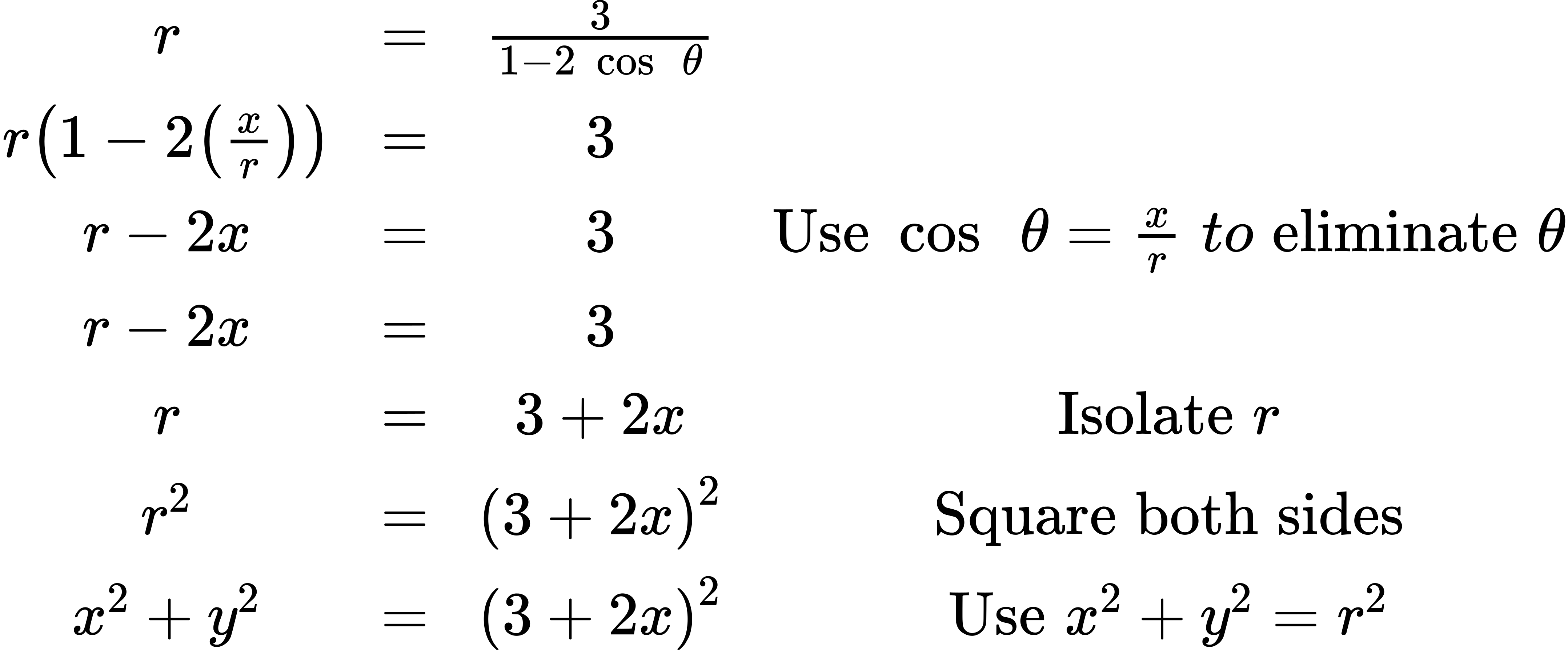

Notice that the equation [latex]r=2sec θ[/latex] drawn on the polar grid is clearly the same as the vertical line [latex]x=2[/latex] drawn on the rectangular grid (see Figure 12). Just as [latex]x=c[/latex] is the standard form for a vertical line in rectangular form, [latex]r=csec θ[/latex] is the standard form for a vertical line in polar form.

A similar discussion would demonstrate that the graph of the function [latex]r=2csc θ[/latex] will be the horizontal line [latex]y=2[/latex]. In fact, [latex]r=c \: csc θ[/latex] is the standard form for a horizontal line in polar form, corresponding to the rectangular form [latex]y=c[/latex].

Example 10

Rewriting a Polar Equation in Cartesian Form

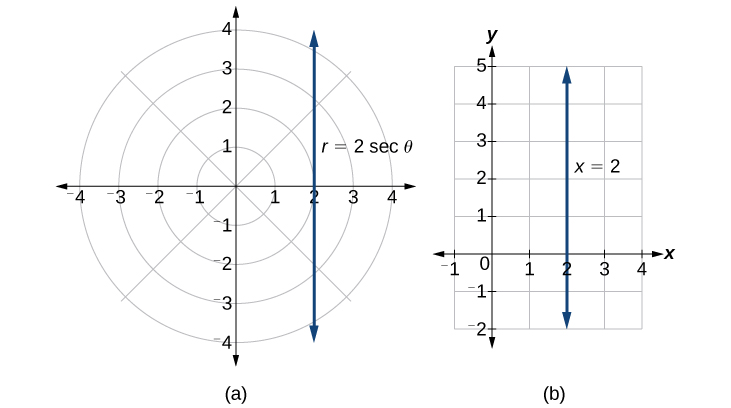

Rewrite the polar equation [latex]r=\frac{3}{1−2cos θ}[/latex] as a Cartesian equation.

Show/Hide Solution

The goal is to eliminate [latex]θ[/latex] and [latex]r[/latex], and introduce [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex]. We clear the fraction, and then use substitution. In order to replace [latex]r[/latex] with [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex], we must use the expression [latex]x^2+y^2=r^2[/latex].

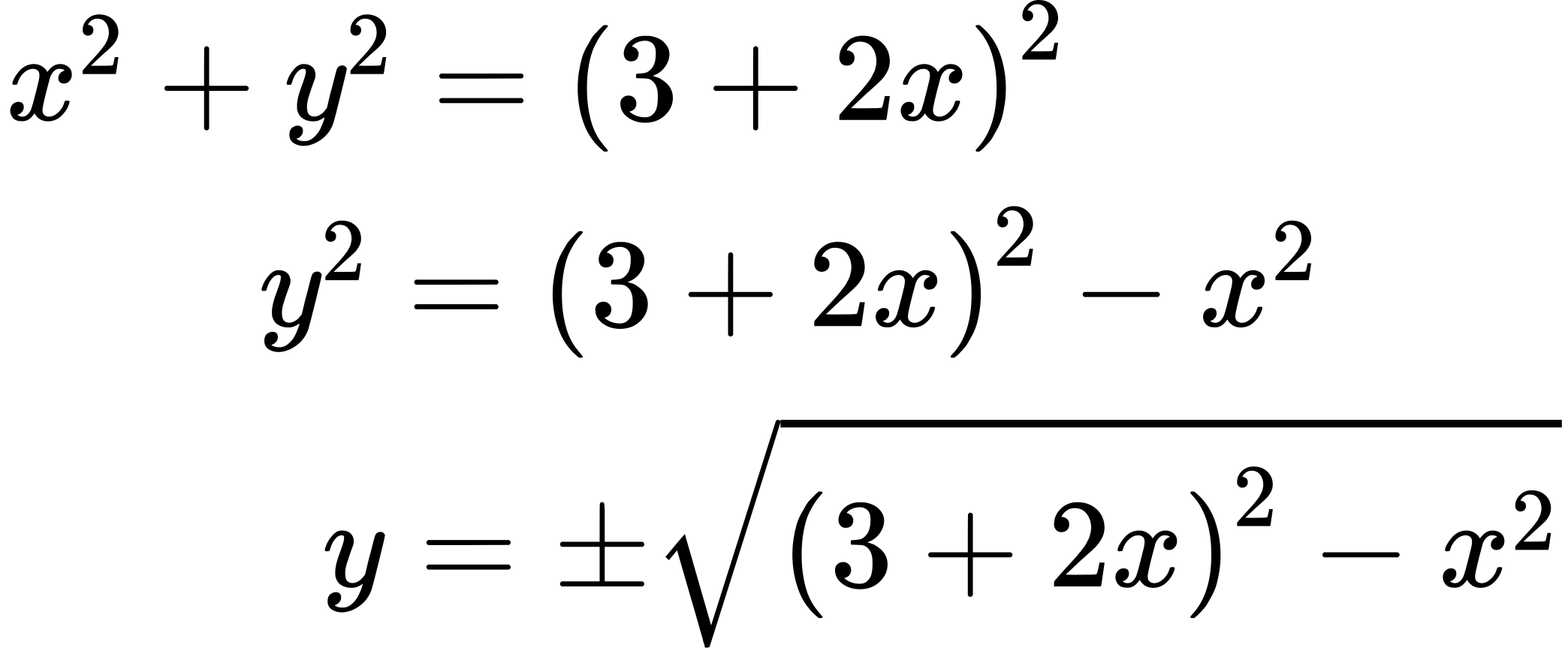

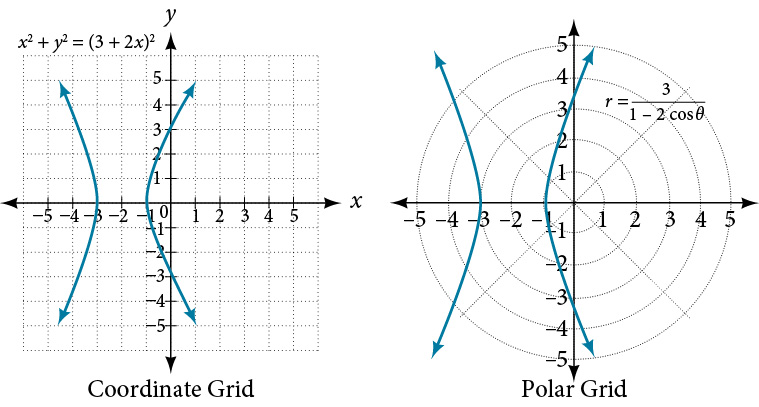

The Cartesian equation is [latex]x^2+y^2=(3+2x)^2[/latex]. However, to graph it, especially using a graphing calculator or computer program, we want to isolate [latex]y[/latex].

When our entire equation has been changed from [latex]r[/latex] and [latex]θ[/latex] to [latex]x[/latex] and [latex]y[/latex], we can stop, unless asked to solve for [latex]y[/latex] or simplify. See Figure 13.

The “hour-glass” shape of the graph is called a hyperbola. Hyperbolas have many interesting geometric features and applications, which we will investigate further in Analytic Geometry.

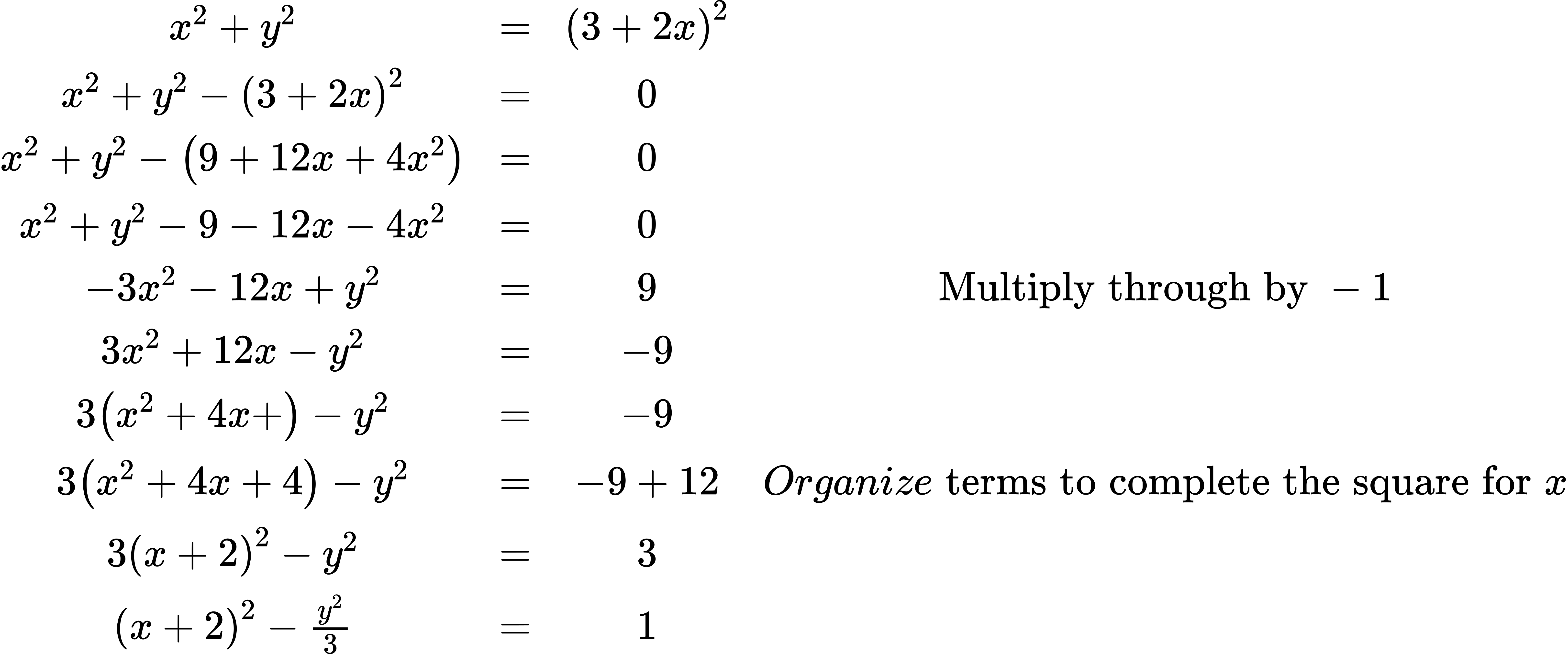

Analysis

In this example, the right side of the equation can be expanded and the equation simplified further, as shown above. However, the equation cannot be written as a single function in Cartesian form. We may wish to write the rectangular equation in the hyperbola’s standard form. To do this, we can start with the initial equation.

Try It #5

Rewrite the polar equation [latex]r=2sin θ[/latex] in Cartesian form.

Example 11

Rewriting a Polar Equation in Cartesian Form

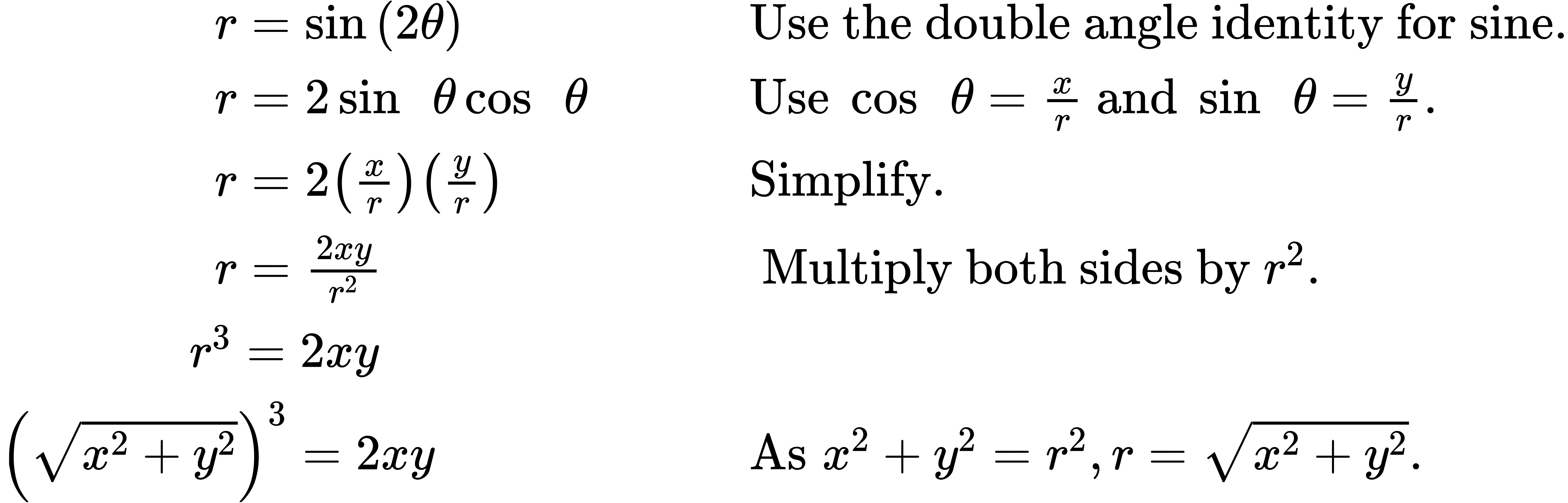

Rewrite the polar equation [latex]r=sin(2θ)[/latex] in Cartesian form.

Show/Hide Solution

This equation can also be written as

[latex](x^2+y^2)^{\frac{3}{2}}=2xy or x^2+y^2=(2xy)^{\frac{2}{3}}[/latex]

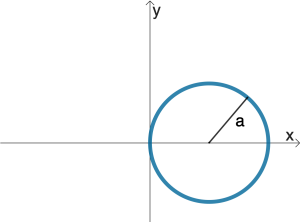

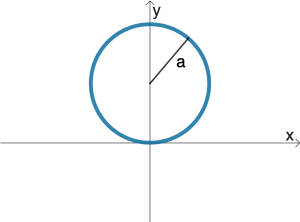

Circles

| Description | Center at the pole, radius [latex]\alpha[/latex] | Passing through the pole, tangent to the line [latex]\theta=\frac{\pi}{2}[/latex], center on the polar axis, radius [latex]\alpha[/latex] | Passing through the pole, tangent to the polar laxis, center on the line [latex]\theta=\frac{\pi}{2}[/latex], radius [latex]\alpha[/latex] |

| Rectangular equation | [latex]x^2+y^2=a^2,\: a>0[/latex] | [latex]x^2+y^2=\pm 2ax,\: a>0[/latex] | [latex]x^2+y^2=\pm 2ay,\: a>0[/latex] |

| Polar equation | [latex]r=a, \: a>0[/latex] | [latex]r=\pm 2a\: cos(\theta), \: a>0[/latex] | [latex]r=\pm 2a\: sin(\theta), \: a>0[/latex] |

| Typical graph |  |

|

|

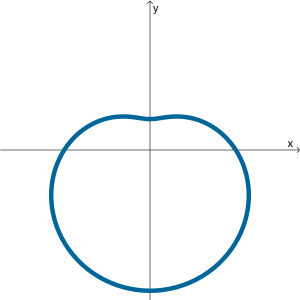

| Name | Cardioid | Limaçon without inner loop | Limaçon with inner loop |

| Polar equations | [latex]r=a\pm a\, cos(\theta),\: a>0[/latex] | [latex]r=a\pm b\, cos(\theta),\: 0 < b < a[/latex] | [latex]r=a\pm b\, cos(\theta),\: 0 < a < b[/latex] |

| [latex]r=a\pm a\, sin(\theta),\: a>0[/latex] | [latex]r=a\pm b\, sin(\theta),\: 0 < b < a[/latex] | [latex]r=a\pm b\, sin(\theta),\: 0 < a < b[/latex] | |

| Typical graph |  |

|

|

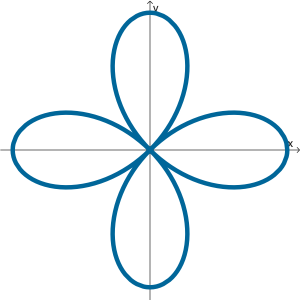

| Name | Lemniscate | Rose with three pedals | Rose with four pedals |

| Polar equations | [latex]r^2=a^2\, cos(2\theta),\: a\neq 0[/latex] | [latex]r=a \, sin(3\theta), \: a>0[/latex] | [latex]r=a\, sin(2\theta), \: a>0[/latex] |

| [latex]r^2=a^2\, sin(2\theta),\: a\neq 0[/latex] | [latex]r=a\, cos(3\theta), \: a>0[/latex] | [latex]r=a\, cos(2\theta) \: a>0[/latex] | |

| Typical graph |  |

|

|

Media

Access these online resources for additional instruction and practice with polar coordinates.

5.3 Section Exercises

Verbal

1. How are polar coordinates different from rectangular coordinates?

2. How are the polar axes different from the x– and y-axes of the Cartesian plane?

3. Explain how polar coordinates are graphed.

4. How are the points [latex](3,\frac{π}{2})[/latex] and [latex](−3,\frac{π}{2})[/latex] related?

5. Explain why the points [latex](−3,\frac{π}{2})[/latex] and [latex](3,−\frac{π}{2})[/latex] are the same.

Algebraic

For the following exercises, convert the given polar coordinates to Cartesian coordinates. Remember to consider the quadrant in which the given point is located when determining [latex]θ[/latex] for the point.

6. [latex](7,7\frac{π}{6})[/latex]

7. [latex](5,π)[/latex]

8. [latex](6,−\frac{π}{4})[/latex]

9. [latex](−3,\frac{π}{6})[/latex]

10. [latex](4,7\frac{π}{4})[/latex]

For the following exercises, convert the given Cartesian coordinates to polar coordinates with [latex]r>0, 0≤θ<2π[/latex]. Remember to consider the quadrant in which the given point is located.

11. [latex](4,2)[/latex]

12. [latex](−4,6)[/latex]

13. [latex](3,−5)[/latex]

14. [latex](−10,−13)[/latex]

15. [latex](8,8)[/latex]

For the following exercises, convert the given Cartesian equation to a polar equation.

16. [latex]x=3[/latex]

17. [latex]y=4[/latex]

18. [latex]y=4x^2[/latex]

19. [latex]y=2x^4[/latex]

20. [latex]x^2+y^2=4y[/latex]

21. [latex]x^2+y^2=3x[/latex]

22. [latex]x^2−y^2=x[/latex]

23. [latex]x^2−y^2=3y[/latex]

24. [latex]x^2+y^2=9[/latex]

25. [latex]x^2=9y[/latex]

26. [latex]y^2=9x[/latex]

27. [latex]9xy=1[/latex]

For the following exercises, convert the given polar equation to a Cartesian equation. Write in the standard form of a conic if possible, and identify the conic section represented.

28. [latex]r=3sin θ[/latex]

29. [latex]r=4cos θ[/latex]

30. [latex]r=\frac{4}{sin θ+7cos θ}[/latex]

31. [latex]r=\frac{6}{cos θ+3sin θ}[/latex]

32. [latex]r=2sec θ[/latex]

33. [latex]r=3csc θ[/latex]

34. [latex]r=\sqrt{rcos θ+2}[/latex]

35. [latex]r^2=4sec θ \: csc θ[/latex]

36. [latex]r=4[/latex]

37. [latex]r^2=4[/latex]

38. [latex]r=\frac{1}{4cos θ−3sin θ}[/latex]

39. [latex]r=\frac{3}{cos θ−5sin θ}[/latex]

Graphical

For the following exercises, find the polar coordinates of the point.

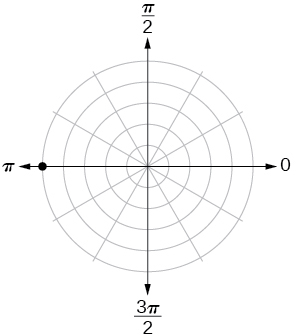

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

For the following exercises, plot the points.

45. [latex](−2,\frac{π}{3})[/latex]

46. [latex](−1,−\frac{π}{2})[/latex]

47. [latex](3.5,\frac{7π}{4})[/latex]

48. [latex](−4,\frac{π}{3})[/latex]

49. [latex](5,\frac{π}{2})[/latex]

50. [latex](4,\frac{-5π}{4})[/latex]

51. [latex](3,\frac{5π}{6})[/latex]

52. [latex](−1.5,\frac{7π}{6})[/latex]

53. [latex](−2,\frac{π}{4})[/latex]

54. [latex](1,\frac{3π}{2})[/latex]

For the following exercises, convert the equation from rectangular to polar form and graph on the polar axis.

55. [latex]5x−y=6[/latex]

56. [latex]2x+7y=−3[/latex]

57. [latex]x^2+(y−1)^2=1[/latex]

58. [latex](x+2)^2+(y+3)^2=13[/latex]

59. [latex]x=2[/latex]

60. [latex]x^2+y^2=5y[/latex]

61. [latex]x^2+y^2=3x[/latex]

For the following exercises, convert the equation from polar to rectangular form and graph on the rectangular plane.

62. [latex]r=6[/latex]

63. [latex]r=−4[/latex]

64. [latex]θ=−\frac{2π}{3}[/latex]

65. [latex]θ=\frac{π}{4}[/latex]

66. [latex]r=sec θ[/latex]

67. [latex]r=−10sin θ[/latex]

68. [latex]r=3cos θ[/latex]

Technology

69. Find the rectangular coordinates of [latex]2,−\frac{π}{5}[/latex]. Round to the nearest thousandth.

70. Find the rectangular coordinates of [latex]−3,3\frac{π}{7}[/latex]. Round to the nearest thousandth.

71. Find the polar coordinates of [latex]−7,8[/latex] in degrees. Round to the nearest thousandth.

72. Find the polar coordinates of [latex]3,−4[/latex] in degrees. Round to the nearest hundredth.

73. Find the polar coordinates of [latex]−2,0[/latex] in radians. Round to the nearest hundredth.

Extensions

74. Describe the graph of [latex]r=a \: sec θ;a>0[/latex].

75. Describe the graph of [latex]r=a \: sec θ;a<0[/latex].

76. Describe the graph of [latex]r=a \: csc θ;a>0[/latex].

77. Describe the graph of [latex]r=a \: csc θ;a<0[/latex].

78. What polar equations will give an oblique line?

For the following exercise, graph the polar inequality.

79. [latex]r<4[/latex]

80. [latex]0≤θ≤\frac{π}{4}[/latex]

81. [latex]θ=\frac{π}{4}, r ≥ 2[/latex]

82. [latex]θ=\frac{π}{4}, r ≥−3[/latex]

83. [latex]0≤θ≤\frac{π}{3}, r < 2[/latex]

84. [latex]\frac{-\pi}{6} < \theta ≤ \frac{\pi}{3}, −3 < r < 2[/latex]