5 The Hollywood Studio System

Learning Objectives

- Learn about the leading production studios during the 30’s and 40’s.

- Understand the human rights issues involved in studio systems.

- Learn about the important aspects of cinema culture during the 30’s and 40’s.

The Hollywood studio system developed as a business model in the 1930s and 40s to control the production of films and to control markets in the U.S. Between 1930 and 1952. Most of the major studios were combined, and the larger studios devoured the smaller companies to create complete control and dominance of the industry. By 1930, most of the principal players in Hollywood were assembled and smaller studios had been taken up.

The Big Five and the Minors

By 1930 the major studios were 20th Century Fox (a combination of the older 20th century pictures and Fox studios), MGM (a combination of Metro pictures, the Golden theatre chain, and the film company of Louis B. Meyer), RKO (a combination of a few radio companies and film companies), and Warner Bros, a studio owned by the three Warner brothers. Two of the brothers retired and left the running of the studio to Jack Warner. Paramount was the most European of the big five. Adolph Zukor ran Paramount and brought in foreign directors, actors, and technicians to give Paramount films an artsy and glossy look.

There were a few minor studios that each specialized in one form of entertainment. Republic made cheap Westerns and Saturday morning serials for children. Disney mostly made cartoons but later switched to a blend of cartoons and live-action films. This was because the live-action films helped to underwrite the cartoon productions, which took longer and cost more. Universal was run by Carl Lamelle, who made mostly low-budget horror films. By 1930, all of these studios competed in a very tight, low-margin market during the depression. Companies had to have constant hits or face bankruptcy. One film’s profits paid for the next film. Two or three disastrous releases could cause layoffs and sell-offs of property, stars, equipment, or real estate. Maintaining the rising costs of production was a day-and-night business.

Studio Methods

The studio system was often referred to as a star factory because Hollywood realized after Chaplin that people liked to view films featuring familiar and dependable stars. Studios virtually owned stars. They paid for their plastic surgery, their cosmetic enhancements, their hair, their clothes, their agents, and their publicity. Sometimes even their residence. They even programmed the star’s personal time and choice of lifestyle, right down to charities and personal appearances. A star’s life was controlled by the studio they worked for because the studio saw them as their property.

There was a lack of human rights within the studio system. If you were gay, you could not exist as a gay person. If you were a child, there were no child labor laws; or the studios disregarded them. If you were a woman, except for a few big stars, you had no control over your properties or the films that the studio chose for you. Your life, your career, your residence, your appearance, were all managed. Most people had to appear grateful to work 18-hour days, sometimes 6 am to midnight to appear in movies. Wages were doled out by contracts that often denied basic worker’s rights. Studios were famous for reprisals against non-complying actors. Humphrey Bogart once angered Warner Brothers studio head Jack Warner and was sentenced to play a lead in a horror movie, one of the lowest jobs in the business. During that time, horror movies were not the venerable terror films of the modern period with lavish special effects, animation, CGI, and clever jump scares. Horror was a discount industry where the cheapest talent and the poorest production values prevailed. Rarities like Dracula and Frankenstein were unusually high-budget versions of stage shows or classic novels (Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein).

Key Takeaways

- The 5 major studios of the 1930’s were 20th Century Fox, MGM, RKO, The Golden theatre chain, and Warner Bros.

- Studios in the 30’s had complete control of their actors and actresses, viewing them as property.

- Horror was originally seen as the lowest job for actors; the genre was not as lavish and exciting as it is in today’s age.

Vertical Integration: Owning it All

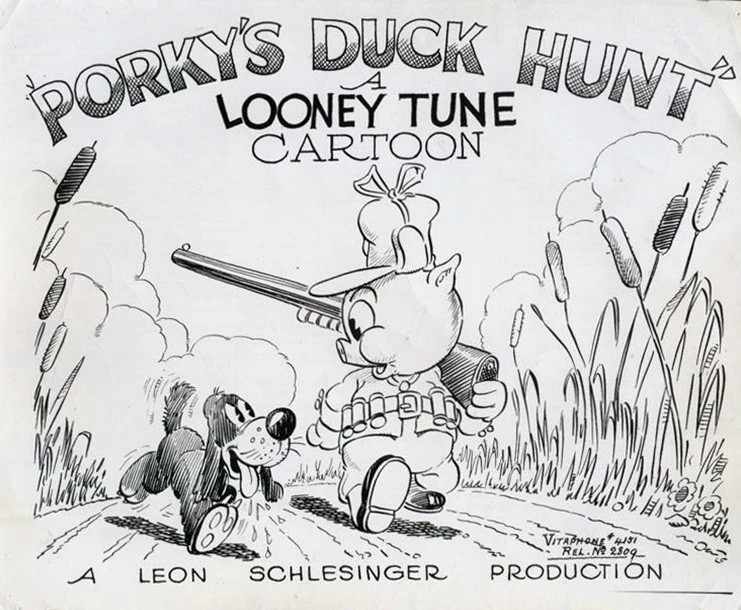

Like the factory production methods of Henry Ford, studio systems adopted tightly controlled conventions of movie production. Studio system films weren’t always wildly creative. Studios simply created a series of films that utilized contracted players, contracted directors, and followed very precise formats of filmmaking. This business model was an example of vertical integration. Studios sought to control all aspects of production and eliminate competition from companies outside the Hollywood area. Vertical Integration meant controlling production, distribution, and exhibition. This meant that all films were built, directed, and printed in Hollywood. The five studios controlled all aspects of the films they made. Each studio had hierarchal systems in place, assigning jobs with lower desirability to newcomers, or as punishments for established workers. The lowest of the low at Warner Brothers was considered to be the animators that made the Looney Tunes cartoons. They were banished to the outskirts of the studio on the area near the studio fence, a series of frame huts where animators had to draw in unairconditioned bungalows.

Looney Tunes Advertisement

This space was known as cockroach terrace. The studios made a lot of money from Looney Tunes but did not respect or appreciate animators like Tex Avery, Chuck Jones, and Fritz Freling. The animators at Warner’s responded by constantly producing cartoons that ridiculed or parodied Warner Brothers own films and stars. The animators knew they were wild and oftentimes annoying, so they were happy to be away from the main offices. Closer to the main buildings were the secondary studios where grade B, minor films were filmed with minor actors. At the center of the Warner’s lot was the big A studios where major stars like Humphrey Bogart and Bette Davis created their classic films. These stars had a choice of some co-cast members and some say in the direction, but the studio heads made all final decisions. In the main buildings, there were corporate offices for studio heads. Usually, these offices featured luxurious decorations to display the power of the giants in the industry.

A major part of the studio complex was accounting. Hollywood accountants were described as “magic accountants,” because outward appearances would illustrate that given films were hits, but the accountants’ report of the costs might show the opposite. The accounting process took into account the use of facilities, technicians, artists’ fees, acting talent, directors, studio production costs, writers, extras, and miscellaneous costs (which could often turn a successful film into a loss, at least for tax purposes).

Apart from the studio facilities, the majors owned all the major distribution of all films throughout the country. Big reels of physical films had to be transported by big trucks across the country to every small town that had a movie theatre. Even small towns of 10,000 people or less would have a theatre. Remember, apart from radio and live theatre, film was the only form of evening entertainment for most Americans. Most major studios released new films every week, and audiences would go see the week’s big hit, returning to the theatre weekly to see new hits as they arrived. In large cities, the Warner’s, Fox, and Paramount trucks would roll into town weekly with new films. Later reels could be mailed to cities for pick up by downtown theatres. As films circulated across the country, prints would be traded from theatre to theatre. The cost of prints in Technicolor was expensive, so the number of prints made weighed against a film’s profits. A ragged print with burn marks, scratches, or sound dropouts could annoy audiences and diminish admissions. This would depress revenue, so keeping theatres stocked with quality prints was in the best interest of the distribution chain. Each studio had mail rooms, trucking lines, print facilities, distribution points, employees, and full divisions devoted to distribution tasks.

The final aspect of vertical integration was the theatres for exhibition. The studios built beautiful theatres, often referred to as movie palaces. They were large, beautiful buildings with plush velour seats, red carpets, colorful and attractive concession stands, and full-on cuisines. In the height of the depression when disposable cash was at a premium, studios equipped movie theatres with facilities to serve full meals for lunch, dinner, and evening snacks. Stages were equipped with strong sound systems, used to host touring celebrities appearing on major radio stations to support their new film releases. For example, popular thirties and forties actors like Bob Hope and Bing Crosby would host radio shows that would promote their films. They would tour behind major releases through towns on the East coast. Films might open in the East in New York, travel to Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Indianapolis, Chicago, Detroit, Madison, and wind up in Minneapolis. Movie stars were treated like today’s rock stars, staying at the best hotels, doing continual interviews, publicizing the film, and promoting its qualities.

Key Takeaways

- Hollywood movie systems developed a highly controlled and precise format of filmmaking.

- Movie studios owned every aspect of their market, including production, distribution, and exhibition.

- Production- Studios created a series of films that utilized contracted players and directors.

- Distribution- In large cities, the Warner’s, Fox, and Paramount trucks would roll into town weekly with new films. Later reels could be mailed to cities for pick up by downtown theatres.

- Exhibition- The studios built beautiful theatres, often referred to as movie palaces.

Movie Theatres: An American Pass Time

The theatres were a place to commune on the weekends. People could go and stay all day, and many did just that. The economics of the depression were precarious. Many people lost their homes and had to live with other families, in trailers, or camps. If people could find a job (at one point 25% of the workforce was unemployed) people saved their slim wages for a date or a solo venture to the movie theatre. Food was cheap, and these theatres were wide-ranging entertainment centers. Big bathrooms for big families, arcades where people could play pinball, and other novelties. Music was playing through speakers everywhere throughout the theatre. The sound was resonant and warm. The theatres were built to contain crowds for 18 hours on a weekend. Kids occupied Saturday morning with cartoons, short subjects, travelogues, and weekly newsreels photographing and filming national events. These shows might extend from 8 am until noon. Custodians would clean up soda bottles and popcorn, and there would be a transition to afternoons which might be teens or pre-teens, families, and older patrons.

Sometimes theatres would host cheap bingo, scrabble, and Pictionary style games with projectors and sound systems. Audience members might be called on stage to help call bingo numbers. Winners might win depression glassware, pots and pans, silverware, and plate sets. People too poor for household items might win them at bingo for a nickel investment in a set of bingo cards. Big swing bands appeared on stage in some venues and audiences would dance the foxtrot in the aisles. Everyone saw almost everyone from the community at the theatre. It was a place for social gathering and social binding. More newsreels, news programming, serials, horror movies, crime thrillers, and other B features would be programmed in the afternoons.

Evening features came after a dinner menu of snacks and more substantial foods, including hotdogs, chips, peanuts, cotton candy, popcorn, and sometimes pizza, soup, and other more exotic items. Again, bands and games would fill in the intermission hours. People might come to the theatre early to win a set of glasses or there might be a free raffle of items, a collection for the needy, or possibly a USO collection for troops fighting during World War Two. Many people pitched in to help at theatres, as during the depression and war years, many men either were overseas, at world camps, or details and could not be home. Many were living and dormitories and sending money home to their families. Women pitched in by serving food, running projectors, tearing tickets, and managing theatres. At around 7 pm, an evening double feature would begin with hit movies introduced by touring stars. Bob Hope and Bing Crosby appeared, performed a stage show, sang songs with a big band, sometimes broadcast a live radio show, and entertained fellow actors and other touring stars. There was a lot of cross-over between radio and film, and advertisements for products that supported film actors and radio shows would be included. Popular products were often sampled and given as hand-outs at the theatres. At special holidays like Christmas and Halloween, masks, tinsel, or other free items would be distributed. After the first feature there might be another stage show, and then the main feature would premiere at 8 or 9 pm. Afterwards, most people finally went home exhausted, but young people might listen to a small swing combo or a jazz band, eat more food, and enjoy more soft drinks. Dancing and games would end the evening, and often the theatres cleaned and closed after midnight. Theatres generated a culture that satisfied American needs for entertainment for nearly two decades. They were uncontested capitals of film pleasure.

Key Takeaways

- Movie theatres were made with the intention to keep customers occupied all day.

- Theatres had games, prizes, cheap food, and music.

- During WWII, women volunteered at theatres to keep them running.

The Hollywood Movie Machine

The success of Hollywood studio systems was due to their operation of every facet of production including the development and creation of the film itself, the writers, and the cameras, so that they could actually control what had been shot and produced that day. All was contained in house. They had built in development facilities so that film could be seen at night the same day it was shot. Productions moved forward daily and studio chiefs watched with actors, technicians, and directors. If the studio didn’t like a film, they could end it in an evening. Studios would push for all productions to move forward, only stopping the films they felt were absolutely necessary to discard. A production started and not finished lost money for the studio, but if a film were to harm the reputability of the studio, it would cost them much more than the production of one film. Money was a concern, but so was prestige and good publicity.

Studios like MGM became extremely proficient, constantly developing scripts hiring writers, hiring actors, hiring directors, and producing films on a regular basis. MGM bragged that it could produce a film a week or 52 films a year, and it called itself the film production factory. People often jokingly called it the dream factory. Hollywood films could be distributed to every city in the nation and to every movie theater in the nation. This strong distribution network throttled product, and studios only distributed films that they either created or had created with an independent producer.

Today, many films partner with streaming services such as Netflix to maximize audience and revenue. Netflix spends well over 10 billion a year to produce its own massive slate of productions to compete against older and more established studios. In recent years, Amazon and Netflix have muscled into the complex business of making films and their efforts have opened the production market somewhat.

Reading Comprehension

- What human rights issues occurred within the Hollywood studio system during the 30’s and 40’s?

- How did the Big Five movie studios use vertical integration?

- What are some features of movie theatres in the 30’s and 40’s?

Films:

Ford, John: Stagecoach (1939)

Van Dyke, S. S.: A Night at the Opera (1935)

Werks, U. B.: Snow White (1937)

McCarey, Leo.: Love Affair (1939)

Curtez, Michael: Casablanca (1942)

Welles, Orson: Citizen Kane (1941)

Warner Bros. Cartoons (formerly known as Leon Schlesinger Productions from 1933 until 1944), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons