7 German Film

Learning Objectives

- Learn about the History that shaped German film.

- Learn about some of the most important German films from the early 20th century.

- Learn about the impact of Hitler’s regime on German filmmakers.

What country gave us early vampires, science fiction worlds, and dark psychological drama? Germany! Early German cinema was prompted by a variety of traumas that affected the German people in the early 20th century. First, there was the rise of militarism in Germany under Bismarck, and the belief that the German people could be a great military power. The people of Bismarck were promised that they would be military leaders of Europe, and they were led into battle in World War I. Germany was soundly defeated, and the price for militarism and aggression were high. The German people were punished with high repayment costs after the war. They were blamed for causing the war. The people were horrified that they lost the war, they were more horrified by the huge cost of war they would have to pay back. The costs bankrupted the society and ruined the German economy. Their economy was in chaos for most of the next 10 years. There was massive fighting between fascists and communists. The military industrial complex collapsed. The new government, the Weimar Republic government, was riddled with corruption. Germany couldn’t accomplish very much. People lived in abject poverty for 10 years between the end of World War I and the 1930s, and then they had to cope with a worldwide depression in the 1930s. However, fascism and the rise of Hitler brought new perils. The German people became involved in the Second World War due to the influence of the dangerous dictator Adolf Hitler. Life for the first half of the twentieth century was chaotic and uncertain for most Germans, and it is reflected in the vigor of their cinema.

The instability in Germany created an odd artistic climate for making films. First, there was little money for film production. A style that emerged and flourished in the 1920s was a style known as Expressionism. Expressionist film erupted out of the art movement of Expressionism, and was noted for heightened color, extreme exaggeration, distortion of figures, and the abstraction of space, so that nothing appeared realistic. The worlds created by expressionism were manufactured worlds in which abstract, extreme, unusual vistas became the norm. Unusual angles and exotic landscapes peppered this extreme style. Many of the images of expressionism in cinema appear abstract, ghostly, and haunting.

Expressionist painting by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner entitled Berlin Street Scene, 1913

Key Takeaways

- Following World War I, Germans endured poverty for 10 years leading up to the Great Depression.

- Germans faced adversity from other countries, as they were blamed for causing the war.

- The instability in German prompted an art movement called Expressionism, which featured dramatic colors, abstracted figures, and distorted reality.

German Film: The Foundation

Prior to World War I German cinema was on the road to great success. There were over 1500 theaters by 1914, but the European cinema went into a slump because of the massive production of American cinema, that out produced Europe and catered to popular tastes. The American film business did not waste time on developing such unique genres, they were more concerned with volume and profits than art and style. Further American cinema developed star system actors, and this attracted more people to their movies. Furthermore, German cinemas and the art and business suffered greatly due to the war and the costs of World War I. There were huge economic shortages in every area. Still, people in Germany thoroughly enjoyed the field of cinema, and attended the movie theatres regularly. Weimar cinema existed in a completely different place than cinema in the rest of Europe. Abject poverty, political chaos, and instability created a tentative art. Unable to afford huge sets, big costumes, extensive productions, props, and the capacious production facilities of the US, German filmmakers had to find new ways to provide a mood, create a feeling, and convey emotions in a film. They explored much darker themes than Hollywood films. They showed more sexuality, crime, immorality, social decadence, government destruction, financial decline, a mistrust of concepts of progress, and a fear of technology. Therefore, films in Germany became darker, claimed a darker subject matter, and maintained an obsession with gothic, dark, and mysterious themes. Germany embraced the Gothic horror film, the graphic crime film noir style, and deeply pessimistic views of the human condition. After Hitler came to power, most of the major filmmakers immigrated to the United States to avoid the horrors of his rule. He dominated all media and prevented artists from having individual expressions. He jailed and murdered many artists that disagreed with him. The German ex-patriots brought with them extensive skills. Many German artists created horror films for Universal Studios and nurtured the dark form of crime movies, so film noir became more popular in American theaters in the 1940s and 50s. German filmmakers were not only important in Germany, but they were also important in world cinema, particularly in the United States. German filmmakers helped produce the American films of the thirties, forties and fifties, transforming American scenography with their expressionist visual sense.

German Film: Horror Icons

Many of the German films in the 1920s had a massive effect on American films that came later. Amongst them is the 1920 Robert Wiene production of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In Caligari, a man who is being treated for a massive paranoia and psychosis believes that his doctor, Dr. Caligari actually has a secret life as a mad scientist. He believes his doctor is sending out a monster at night that is killing women and holding people hostage, and that the doctor is evil and means to do harm to him. He sneaks out of his room at night and watches the doctor release his robotic man, a half human monster that menaces and murders women.

Stills From The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

At Dr. Caligari’s command, the monster plagues the city by kidnapping women and killing people. By the film’s end, he realizes he is the doctor’s next intended victim. The twist ending has him awaken from a fever dream to understand that the good doctor has been treating him all along, and that the entire film has been his own paranoid psychotic dream. The doctor is not a horrible monster, but a very nice person who has been treating him through his psychotic episode. In the end he discovers there is no evil doctor, no conspiracy, no kidnapped women, and no murders. It has all been his paranoid delusion. It’s a film about the appearances versus reality of everyday situations.

The American studios were watching this new brand of film emerging from Germany. The next big feature was F. W. Murnau’s 1922 epic, Nosferatu, “a symphony of horror.” It was one of the earliest horror films based on Bram Stoker’s novel, Dracula, from the 1890s. Nosferatu literally means vampire, and Murnau referred to the film as a symphony to tie it to its romantic novel origins. It is a symphonic and operatic work where characters glide in and out of the frames. Though Murnau had a miniscule budget, he used light, shadow, time, and movement to build suspense and introduce the vampire. Using these marginal means to portray the horror, rather than complex sets or special effects, he captivates and chills the viewer. Here the vampire is named Count Orlok, because Murnau could not obtain permission to use Bram Stoker’s novel as the basis for his film. Stoker’s widow, a British nationalist, refused to sell rights to the novel to a German company. Many of the best scenes are simply shadowy sequences where Orlok lurks and menaces the cast. His silhouette descending a staircase became one of the film’s iconic moments and one of the most iconic moments in cinema history. The film comes to a crescendo when Nosferatu, smitten with lust for a young woman, overstays his feast on her blood. As the sun rises, he realizes he is in jeopardy. Though he tries to escape by slipping past a window, his image caught in the rising sun, he is transfixed and incinerated by sunlight.

German Film: Financial Themes

Another important film from 1922 is Murnau’s lesser-known film Phantom, in which a man is haunted by the image of a woman that he has seen. Desperate to find answers, he spends money trying to track this woman down. Underneath is a metaphor for financial obsessions. He obsesses over spending and not over living a good life.

From the same era in 1924 is Murnau’s, The Last Laugh, another financial parable about a country facing debt, spiraling inflation, and decreased buying power of the German currency, the marc. Laugh is the story of a doorman who works for a fancy hotel. When times turn financially unstable, the hotel closes, and he loses his job. The man is obsessed with his role as a doorman, and without his beautiful frock coat, his uniform, and his ability to make money, he withers. The film is provocative, showing the hero is reduced to working as a bathroom cleaning attendant. He is derided by his family. They make fun of him and chide him for losing his job. At the end he wins a fortune at a lottery, and his unlucky situation is reversed through money. He has status and power again. The film shows that the only thing people respect about him is his station in life and his money, not his actual qualities as a human being. The Last Laugh shows the irony in people’s responses when one loses verses gains fortune.

Key Takeaways

- The Weimar Republic, which governed Germany after World War I, was faced with political chaos. This, along with abject poverty, prompted German directors to adopt darker themes in their films

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu are some of the most influential horror movies of all time, impacting the course of American film thereafter

- Movies like Phantom and The Last Laugh illustrate the financial hardship faced by Germans during this time period

German Film: The Lasting Impact of Germany’s Dark Themes

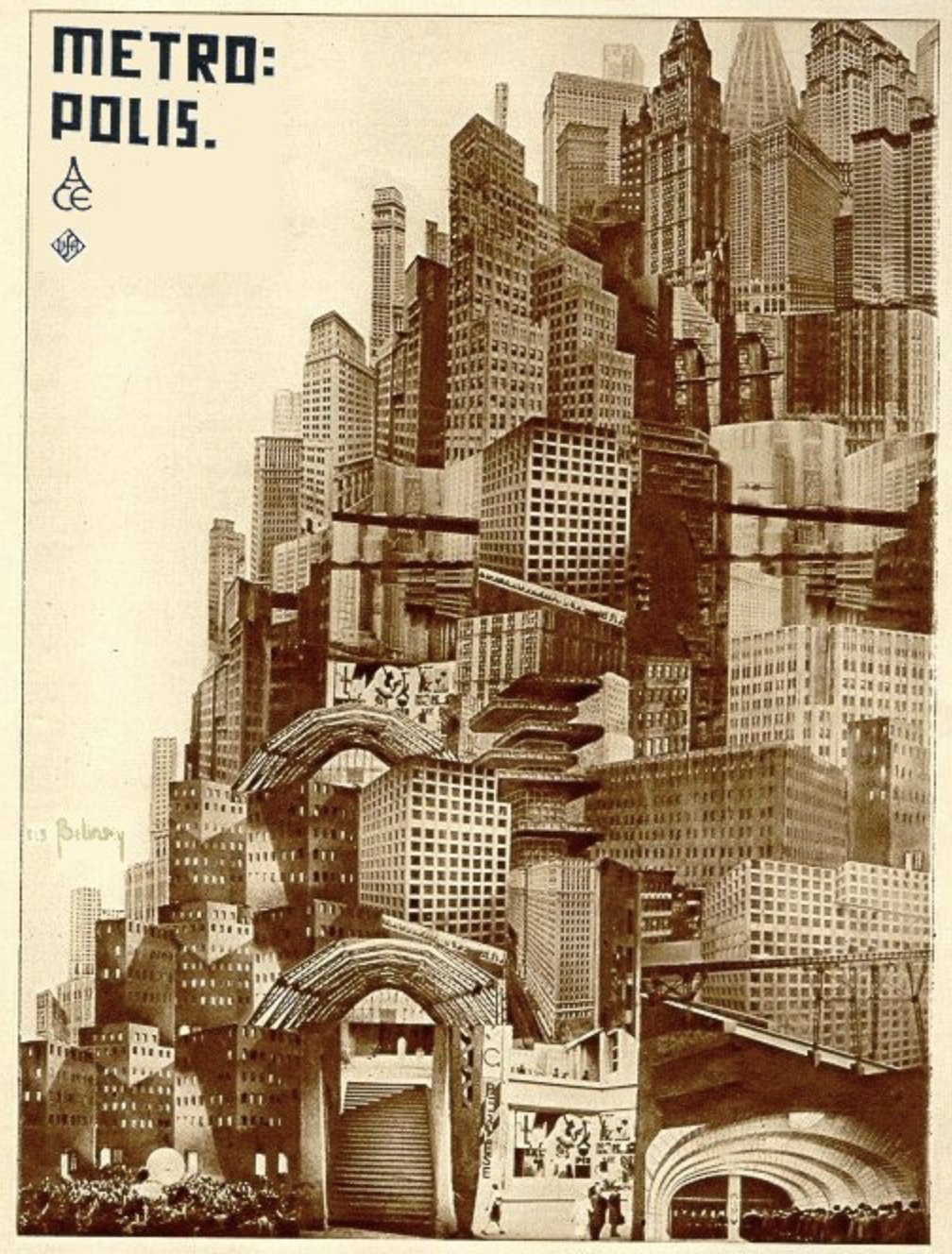

In 1927, Fritz Lang produced one of the greatest German films of the era, Metropolis. It came at the very end of the German silent film era. It’s a science-fiction film about a future world in which the people are controlled by a desperate government, very reminiscent of what was to happen to Germany five years later when Nazi rule became reality. In the film, workers worked long and brutal hours, and they often suffered hardship, pain and death on the job. They lived and died tending the great machines that ran the society. There was a scientist seeking new ways to control the people. The forces of oppression captured a freedom fighter, a girl named Maria who was organizing and motivating the workers to rebel. The autocrats in the city realized that to control the people, they must control Maria, so they build a robot to replace her. They transfer Maria’s life energy and consciousness into the robot and make the robot a weird parody of the girl. The robot is revealed, Maria is restored and the society is eventually freed. The film used extensive special effects, animation affects, robots, flying cars, weird dreams, weird machines, and all the elements of German expressionist distortion. In one frightening sequence, when the engineer goes to sleep, he sees a giant skeleton coming out of the city clock and using a scythe to kill him. The film is nightmarish and frightening.

Metropolis was also the subject of an interesting rediscovery a restoration. The film was thought to be only two hours in length, but in recent years a two-and-one-half hour version was uncovered in Germany and restored. Today we have a new version with 30 minutes of restored footage. The unknown version of Metropolis had been missing for 70 years. Metropolis brings up the issues involved in film restoration. Without film restorers many classic films of the past could be lost and particularly films in foreign countries where film restoration was not been widely adopted and film institutes had little money to conduct restoration projects.

Poster for the movie Metropolis

In 1931, one of the last films completed by Fritz (Metropolis) Lang before he departed Germany and Hitler assumed power was a film entitled ‘M’, which told a dark, creepy story of a child molester and murderer. It described a pedophile and murderer who was wanted by the underworld as well. It featured the great character actor, Peter Lorrie who was also a German citizen who fled Germany in favor of the freedom of Hollywood. Lorrie started acting as a player for the famous German director and writer, Bertolt Brecht in the 1920’s. He immigrated to the United States in the 1930s and became very popular for exotic characters in films. He played Japanese detectives (Mr. Moto), monsters and freaks (Cormen’s Poe films), and seasoned criminals in Warner Brothers features (The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca). One of his major starring roles was in The Mask of Demetrious, in which he plays a writer and detective, seeking a criminal who escaped from the law. Lorrie was compelling in The Best with Five Fingers, a retelling of the classic, Hands of Orlac, in which a pianist loses his hands, but has the hands of a murderer grafted onto his arms, possessing the quiet pianist into a murderer. His work with Lang is frenetic and Lorrie holds the screen with a twitchy nervous manner unmatched by most of his peers.

German cinema had a lasting influence, especially on developing expressionistic aspects of cinema. In 1923, Hollywood’s Universal Studios embraced the German aesthetic in a series of horror films produced by German directors and craftsmen working in the US. Many of these films starred top American talents, including silent Horror giant, Lon Chaney Sr., the star of Hunchback, Phantom, and London. This genre began with 1923’s version of Victor Hugo’s gothic classic, The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Later, in 1925 Universal created the original Phantom of the Opera, and also an early vampire film, London after Midnight, and Dracula in 1931. All featured German technicians and aesthetics derived from ideas in expressionism or surrealism. These workers were hired from Germany to utilize their technical abilities and expressionistic style. German directors crossed the Atlantic and made their mark in America such as Paul Leni, who directed The Cat and the Canary in 1927. The most notable ex-patriots include singer/actress Marlene Dietrich (John Wayne’s girlfriend during the Second World War), playwright and screenwriter, Bertolt Brecht and director/actor Erich Von Stroheim.

Key Takeaways

- Metropolis, which predates Nazi Germany by 5 years, was about a futuristic, authoritarian society. 70 years after it was released, restorationists discovered 30 minutes of missing film that had never been shown.

- After Hitler came to power, most directors fled to the United States.

- Famous actors like Peter Lorrie and Marlene Dietrich are among the most notable ex-patriots, including screenwriter, Bertolt Brecht, and director/actor, Erich Von Stroheim.

German Film: Propaganda

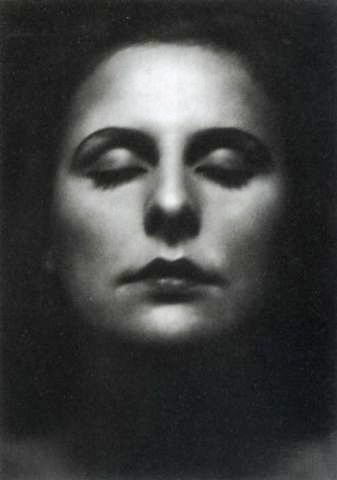

One director stayed in Germany. Her name was Leni Riefenstahl. She had been a talented and beautiful actress in the 1920s. Hitler admired her work and asked her to Berlin to work on propaganda films for the German government; she agreed and made a series of powerful films to propagandize the Nazi regime. She was an important filmmaker for Adolf Hitler because she liked Hitler. She was ready to make the films that Hitler wanted. She had a long life (lived to be 103) and was productive for most of her career.

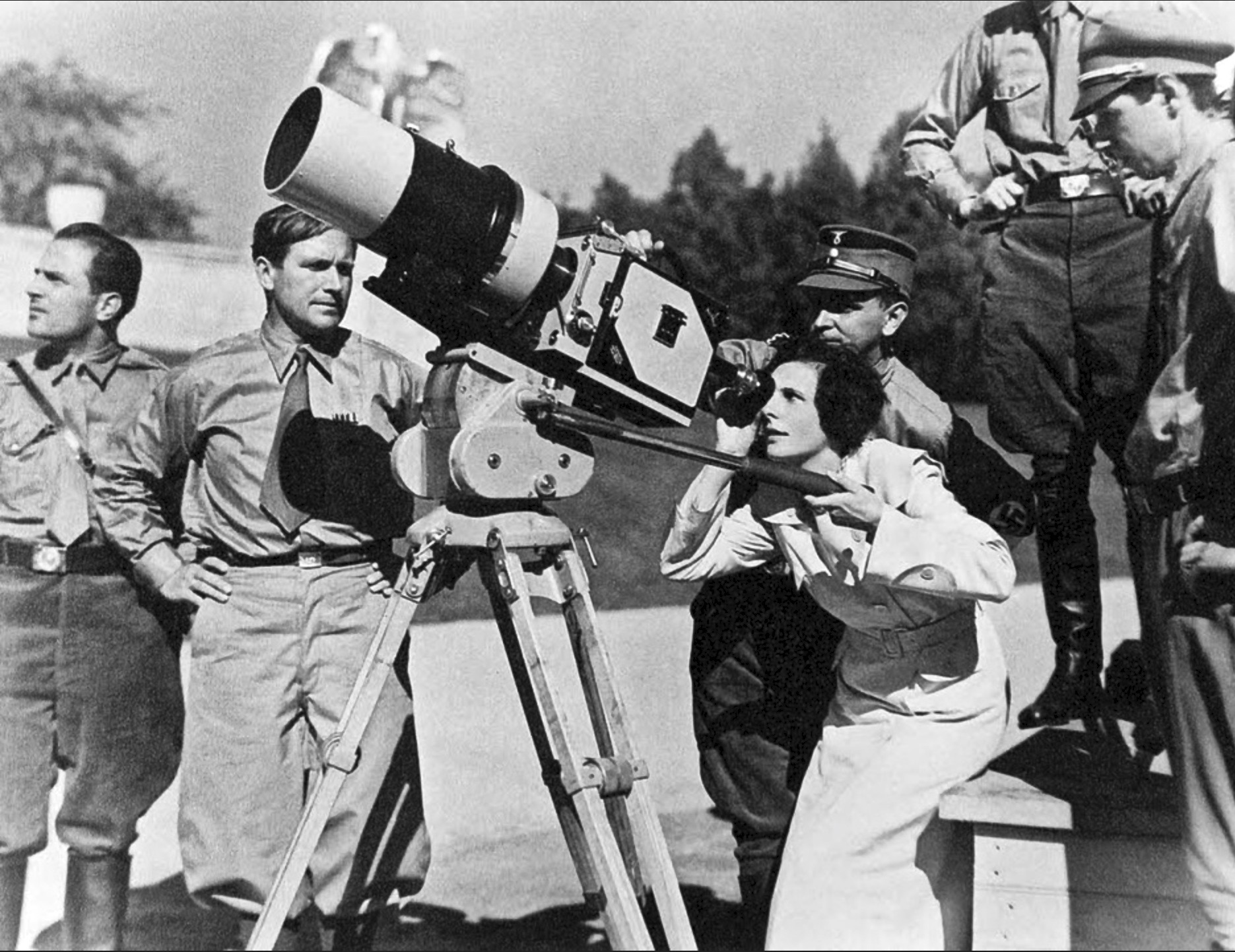

Riefenstahl produced successful films for the Nazi regime that supported the notion of Hitler as a national hero. The first was her staged documentary of the Nazi Nuremburg rally of 1934, entitled, Triumph of the Will (1936). Hitler was portrayed like a God. The film started with Hitler flying into the rally on a plane, and he literally descended from heaven to the crowd of adoring fans. World audiences seeing Triumph of the Will were in awe of the people’s love and veneration for Hitler. They were impressed and fearful of this new unifying German force, the Nazi movement. Hitler was shown flying in like a god descending from the heavens. He strode amongst the troops who greeted him with cheers. They saluted. He modestly entered a car and thousands cheered and thronged him as he strode down the streets as a conquering hero. He gave a magnetic speech, and everyone was in rapt attention to the charming and dynamic leader. The truth is none of that really happened. There was a rally, but everything was staged. Actors were chosen and placed in the crowd. People were brought in to cheer to Hitler. The magnificent parades and set pieces were choreographed, and people were drilled on how to react and what to do. Some of the shots were from a low angle to make things look bigger, more powerful, and more colorful than they really were at the time. Nothing was spontaneous. True, Hitler did have followers, and many devout followers, but the massive crowds, the mesmerized wonder about Hitler, and the public love of the man was entirely the work of Leni Riefenstahl and her complex directorial hand. Her greatest achievement was making this wholly unnatural event look natural and unplanned. For this, she was a genius. She could make the staged film look like a real event. Today, people see Triumph of the Will and think, this was the reality of the era, and that Hitler was loved and adored. This was not the case. Hitler’s regime was brutal and manipulative, and protest or rejection of Hitler was not tolerated. Opponents to Hitler’s ideology were jailed, beaten, or killed. Sadly, the only way that Hitler could have a film made about him that flattered him, was to have it manufactured and staged. Riefenstahl effectively used camera angles and tracking shots to make Hitler look like a powerful and magnetic leader.

Leni Riefenstahl Films a Nazi Rally, 1934

Riefenstahl made a second film for Hitler in 1938 entitled, Olympiad, which covered the German Summer Olympics in 1936. The filming was very innovative, with camera shots from balloons, underwater, and aerial images. The film was in two parts, both about 2 hours long. It was controversial because at the Olympics, Hitler refused to shake hands with American track star Jessie Owens, an African American runner who soundly defeated the German team. Owens achievement was monumental. In truth, Owens was the real star of the Olympics, but Olympiad obscures his achievement, because Hitler refused to be seen as wrong. For the most part, the film she created portrays the greatness of German athletes against other athletes in a world stage. However, it minimized the accomplishments of Jesse Owens and turned a blind eye to Hitler’s blatant racism towards him. He was one of the greatest athletes in American history and did a fantastic job under tremendous pressure in Nazi Germany. There have been several films about his achievement. Nonetheless, Riefenstahl made a movie about the Olympics that Hitler approved. She staged footage and manipulated the perspective of the events, which was common practice in maintaining the image of Hitler as a hero. The Olympics film was made as another form of justification of Hitler’s policies, prejudice, and the idea of an Aryan nation, putting a blonde-haired, blue-eyed people above everyone else.

Leni Riefenstahl films Olympiad, 1936

After the war and Hitler’s suicide, Riefenstahl was put on trial for war crimes. She denied she was a Nazi and claimed she was a filmmaker first and last. She said she was an artist in service to a dictator. She simply made the films he wanted her to make. Though she supported Hitler and made pro-Hitler films, little evidence could be found to convict her. People tried to prosecute her for being a Nazi, but her argument was that she was a good film director, not a Nazi, and the fact that she had been a good filmmaker for Hitler wasn’t a crime. While this may be true, the level to which she uplifted Hitler, and with such mastery, made this statement difficult to believe. She lived another 60 years, and after the war began making films in Africa, featuring the lives and accomplishments of African tribesmen. It was an ironic and bizarre turn of events for a filmmaker that was associated with Nazism and Hitler. Some thought it was Riefenstahl’s repudiation of her past and some thought it was her service and penance for espousing Nazi ideas during the war. Riefenstahl’s conversion to being a naturalist and a supporter of indigenous people, recording their lives, seemed to be a real and genuine conversion from one of the most hated filmmakers of the World War Two era, to one of the real masters of documentary filmmaking in her later life.

Key Takeaways

- Leni Riefenstahl was a film director for Hitler in Nazi Germany.

- Her movies, Triumph of the Will, and Olympiad were made with the goal of uplifting Hitler and his ideology.

- After the war, Riefenstahl was tried for war crimes but was ultimately released due to a lack of evidence.

- Riefenstahl made a surprising switch to documentary film after World War Two, filming indigenous people and nature.

The history of German cinema is very important to the West, especially the films that were made in the 1920s, during the German Expressionist movement. Social disruptions and economic shortages of the Weimar Republic gave rise to new techniques, and new styles of German filmmaking that became associated with the expressionistic art movement. German film featured extreme color, extreme emotion, extreme angles, extreme distortion, extreme abstraction of human values, extreme transformation of themes, extreme distortion of reality, so that many of the non-human or non-realistic films reflected the ideas of fantasy, horror, crime, and science fiction. The disadvantage of German films in the Weimar Republic in the 1920s was that the society was unable to sustain the sorts of large cast spectacles that were popular in other countries. Directors in Germany had to find different ways of creating production techniques to create their own style, character, atmosphere, and emotion. Expressionistic filmmakers like Murnau and Lang were also concerned with darker storylines where science-fiction and psychologically disturbed characters espoused expressionist emotions, as directors developed innovative techniques to support their work.

The German methods appealed to American audiences in the 1930s and 40s, as they used light and contrast to create film effects. They used movement and camera angles to create a new, darker, abstracted, form of film than had been seen before in Western Europe. The German style supported the efforts to create horror movies and film noir projects in the United States. These directors and their innovations didn’t just stay in Germany but had a huge impact on American film and world film. Many German directors and technicians struggled to remain relevant in the aftermath of Hitler, enduring a wave of hatred of all things German that lasted throughout the rest of the twentieth century. Further, Germany was divided and weakened throughout the majority of the last half of the twentieth century and had to fight to repair its economy and arts. Despite all of this, German film found ways to survive and remain influential during a disastrous century, and German filmmakers prevailed against the politics and disasters of world wars.

Reading Comprehension

- How did Hitler use film directors to manipulate Germans into following him?

- What factors contributed to the German style of film?

- Describe the characteristics of the expressionist movement, and how it manifested into film.

- How did German film impact American films?

Terms

Expressionism: Expressionism was a format of art that utilized heightened emotions, distortion, bright colors, and abstraction to illustrate a distorted world view. Expressionism transferred extreme emotional angst onto film or canvas.

Nazism: The National socialist movement or the Nazi movement was a fascist form of government popular in Germany and parts of Europe and Asia in the early twentieth century. It derived from central control of the economy and businesses by a strong central government.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Robert Wiene, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Robert Wiene, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Willy Hameister, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Boris Konstantinowitsch Bilinski, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Allgeier family inhertiance, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1988-106-29 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en>, via Wikimedia Commons

Alexander Binder (* 1888 in Alexandria; † 25. Februar 1929 in Berlin)., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Films:

Murnau, F. W.: Nosferatu (1919)

Murnau, F. W.: The Last Laugh (1924)

Lang, Fritz: Metropolis (1925)

Lang, Fritz: M (1931)

Riefenstahl, Leni: Triumph of the Will (1936)

Riefenstahl, Leni: Olympiad (1938)