11 20th Century in American Film

Learning Objectives

- Learn about the changes in film content during the 1960s and 1970s

- Understand the social and political issues that were reflected in the themes during this era

- Learn about the new genres of film introduced in the 60s and 70s, and how these genres reflected a shift in societal attitudes

The 1960s was an important time of transition in American film. Many Americans stopped going to the movies and started watching the new medium of television. Television had been actively programming media including new comedies, transplanted shows from radio, and sporting events, but the filming quality in black and white was deeply inferior to film. By the late fifties, subtle improvements in videotape technology and larger production budgets conspired to make television more watchable. Further, film companies were seeing less viewers, and many were selling their old films to television to obtain badly needed revenue to keep their film studios afloat. Initially, film companies tried to boycott television and tried to freeze them out of product. However, resilient little television stations developed shows, writers and actors. Many borrowed from Broadway productions. Television developed a loyal following of older Americans who disliked the prices and inconvenience of film attendance.

Television had existed for ten years but had begun to rival film with complex camera shots and scripts, young actors, and novel means of storytelling. Further, the medium had the advantage of bringing back stories and popular characters weekly. Film audiences waited years between editions of Tarzan and Sherlock Holmes, much like serial TV in the millennial era. Television had fast production, quick turnaround of shows, and the ability to market new programming quickly. Hollywood had not responded well to television. In fact, most of the major studios refused to make films for television, and only reluctantly in the 1960s did film studios begin to partner with television stations to create films that could be shown in both mediums.

Many of the experiments crossing over from television to film created interesting hybrids in the two forms, and some of the most interesting films in the 1960s used the television form to great effect. Many of these films in the 1960s illustrated that society had changed, and that Madison Avenue in advertising had changed in the same way. The transition to a consumer culture was rapid, and television understood the needs of new audiences. Films of the sixties have an undeniable relationship to television and other media, and if people were puzzled and did not attend such films, the movement towards a grittier, more realistic, more fantastic, and more media-oriented culture was an outgrowth of sixties film experimentation. Some of the key films of the sixties helped to change perceptions not only of film itself but society in general.

Key Takeaways

- In the 1960’s the film industry began seeing losses in revenue due to the rise of television

- Television catered to older audiences who disliked the prices and inconvenience of theatre viewings

- Television rivaled the film industry with their fast production, and the advantage of being able to bring back stories and popular characters weekly

- The film industry tried their best to hold back the success of television, but in the 1960’s they submitted by finally partnering with television stations to produce films that could be viewed in both formats

20th Century in American Film: The Sixties

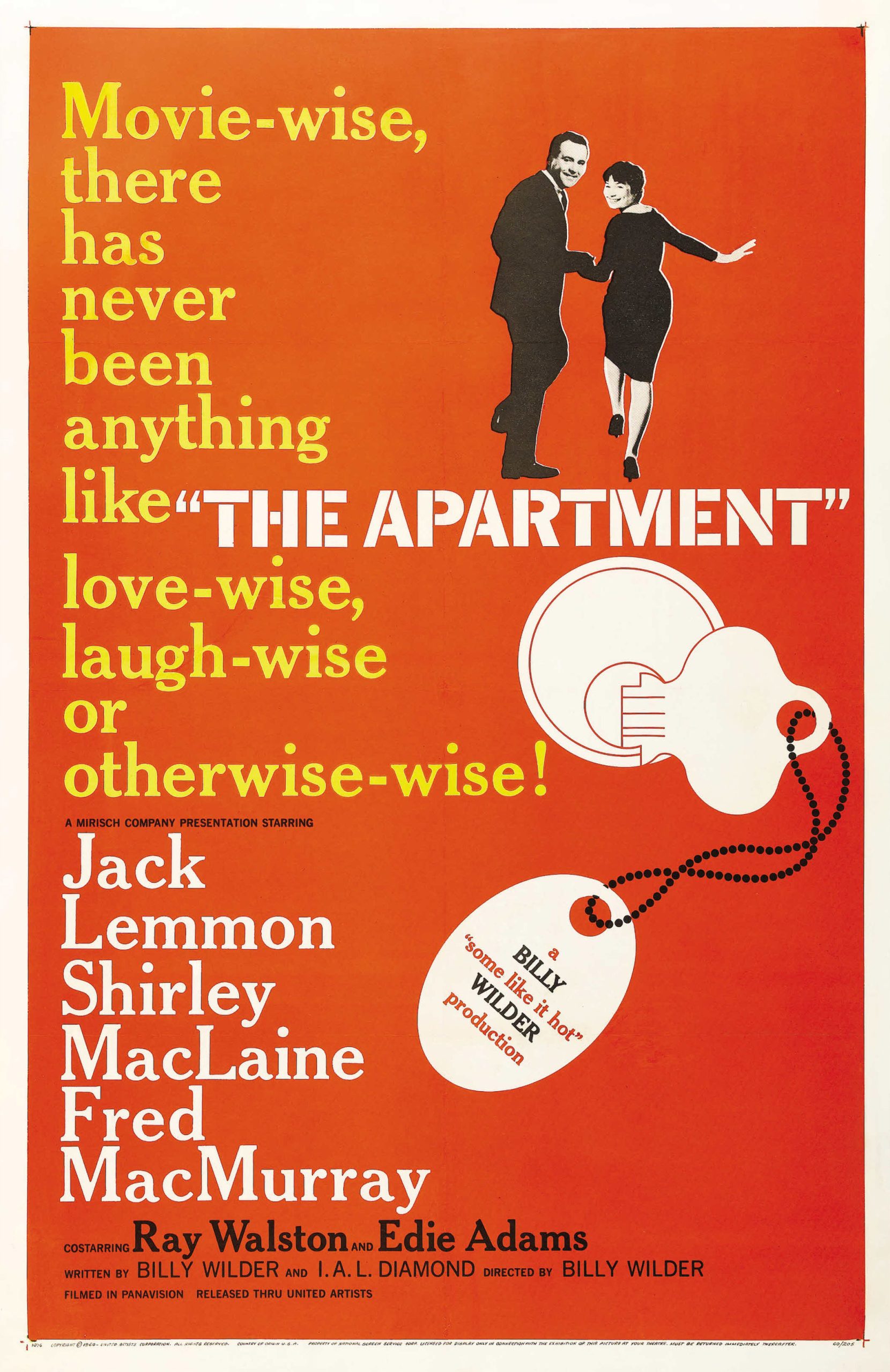

The Apartment (1960)

The Apartment, directed by Billy Wilder and written by Wilder and his co-writer, A.L. Diamond, created a scathing portrait of American culture in the early 60s. The Apartment’s address of American culture resembled the way British films in the era had illustrated the problems in British society in the 1950s and the 1960s, with a class-conscious style, and a sharp insight into society’s morose and taboos. The film pivotally cast generally well-known, Fred McMurray as a classic corporate heel. The film pivots around three important characters.

There is Jack Lemmon, who is functioning as a minor executive in a large company, his corporate boss played by Fred McMurray, and Shirley MacLaine, a rising actress of the time who played a lowly office girl, pining for the men’s affections in the film. Lemmon, to court favor with his boss, offers to loan his apartment to his boss on certain days of the week. The boss is a married man having an affair with the office girl, who falls madly in love with the older man. At first, Lemmon’s character feels no compulsion about loaning his apartment to his boss. But overtime Lemmon’s character falls in love with the girl himself, which creates complications for all. The film deals with the issues of corporatism in America, and how large businesses and large corporate raiders can have authority and power over people’s lives. It also suggests that morality is not present within business. The Apartment is a great indictment of American culture and the disparity between the working class and corporate leaders. It also illustrates that the corporate leaders of society are not better people, just people with more entitlement and more money.

Key Takeaways

- The Apartment is a critique of American culture, much like that of the British films during the same era

- This film addressed a lack corporate morality and class disparities faced in America

- The Apartment highlights the unbalanced relationship dynamics between superiors and their employees, as well as how corporations can control the lives of their workers

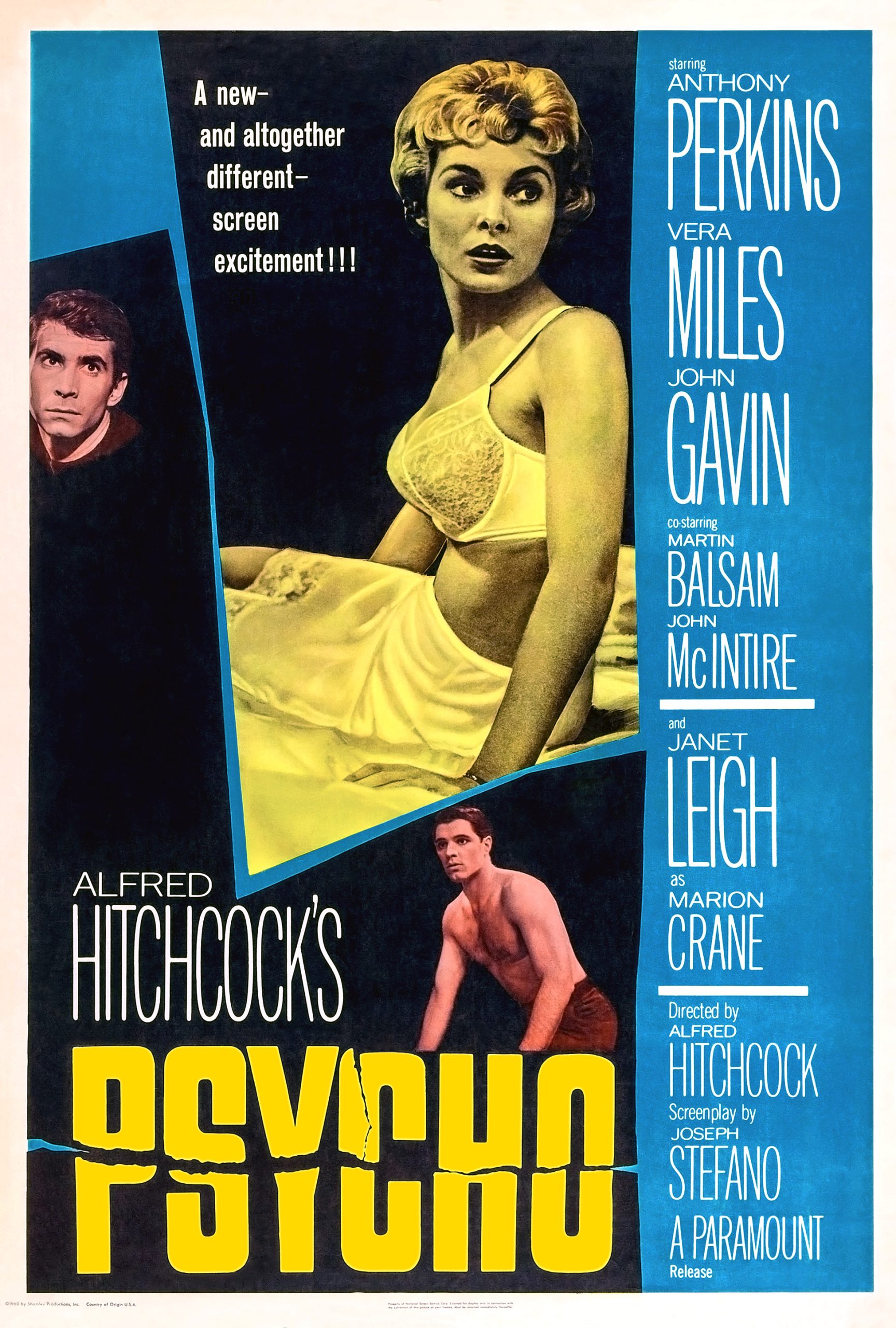

Psycho (1960)

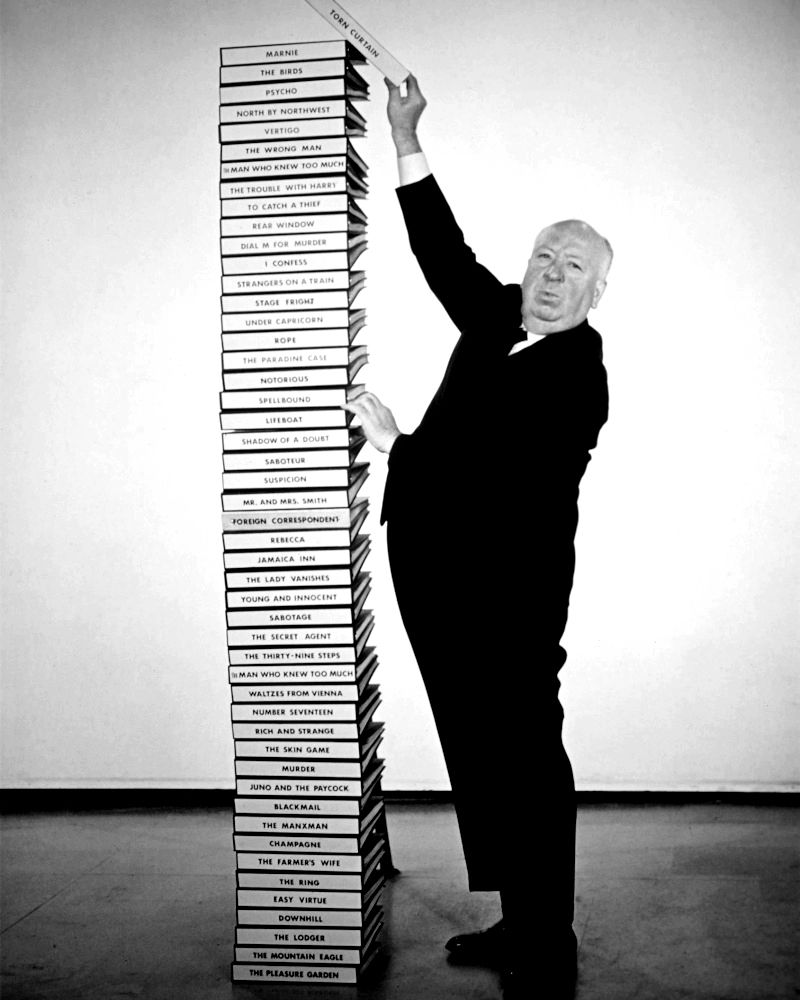

Perhaps not seen as revolutionary at the time, Alfred Hitchcock’s, Psycho, from 1960 is probably one of the most revolutionary films of all time. Directors in the 1960’s were making cheap horror films that were being shown in drive-ins and making millions of dollars, Hitchcock wanted in on the trend. His studio Paramount did not want him to make a cheap horror film because he was a classic director, and he knew how to make really beautiful films. Hitchcock did not see himself as part of the value system of upper-class society and wanted to make films that were entertaining to all segments of society. That’s why he wanted to make a cheap horror film like Psycho.

Poster for Psycho

He chose the story of Ed Gein, who was an important serial killer of the 1950s. His murders in Kansas had made headlines across the country. The story attracted veteran horror writer, Robert Bloch, who had been writing gothic fiction, fantasy, and horror stories since the thirties. He wrote a novel about the case entitled Psycho, and made his crazed protagonist, Norman Bates, a Freudian character engaged with a weird relationship with his mother. Paramount objected to Hitchcock wishing to make a horror movie on such a lowly scale and simply refused to back such a film. Hitchcock was insistent that he could make a great horror film on whatever budget he was given, and he had already been directing a television show, The Alfred Hitchcock Presents, for the last five years since 1955.

Alfred Hitchcock poses for a publicity shoot, 1966

The show was a massive hit, and Hitchcock completely understood the dynamics of television. He liked the opportunity and challenge of coming up with weekly shockers and thrillers. In fact, the show only ended after 10 years because he grew tired of doing it. Further, he was not dissuaded from doing the film of his choice. He was a clever man and had always found a way to produce the projects he wanted to produce. He had the backing of a television network, no small thing, independent capital of his own, and the idea to make low budget horror the way younger producers like Roger Corman were making films. Most importantly, these films were making massive profits. Hitchcock had to find a means to do his film, so he prompted Paramount to allow him to make the film, granted he would put up all of the money for the film. Hitchcock actually mortgaged his home in Beverly Hills to afford the project. He agreed to a very limited budget of $500,000, a small amount even by sixties standards. He agreed to shoot the film in six weeks using his television crew from his weekly program, and he shot the entire film in black-and-white using fairly unknown actors. The only name actor in the cast was Janet Leigh, who played the lead, and a young up-and-coming actor Anthony Perkins, who played the young and creepy Norman Bates.

Hitchcock with Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins

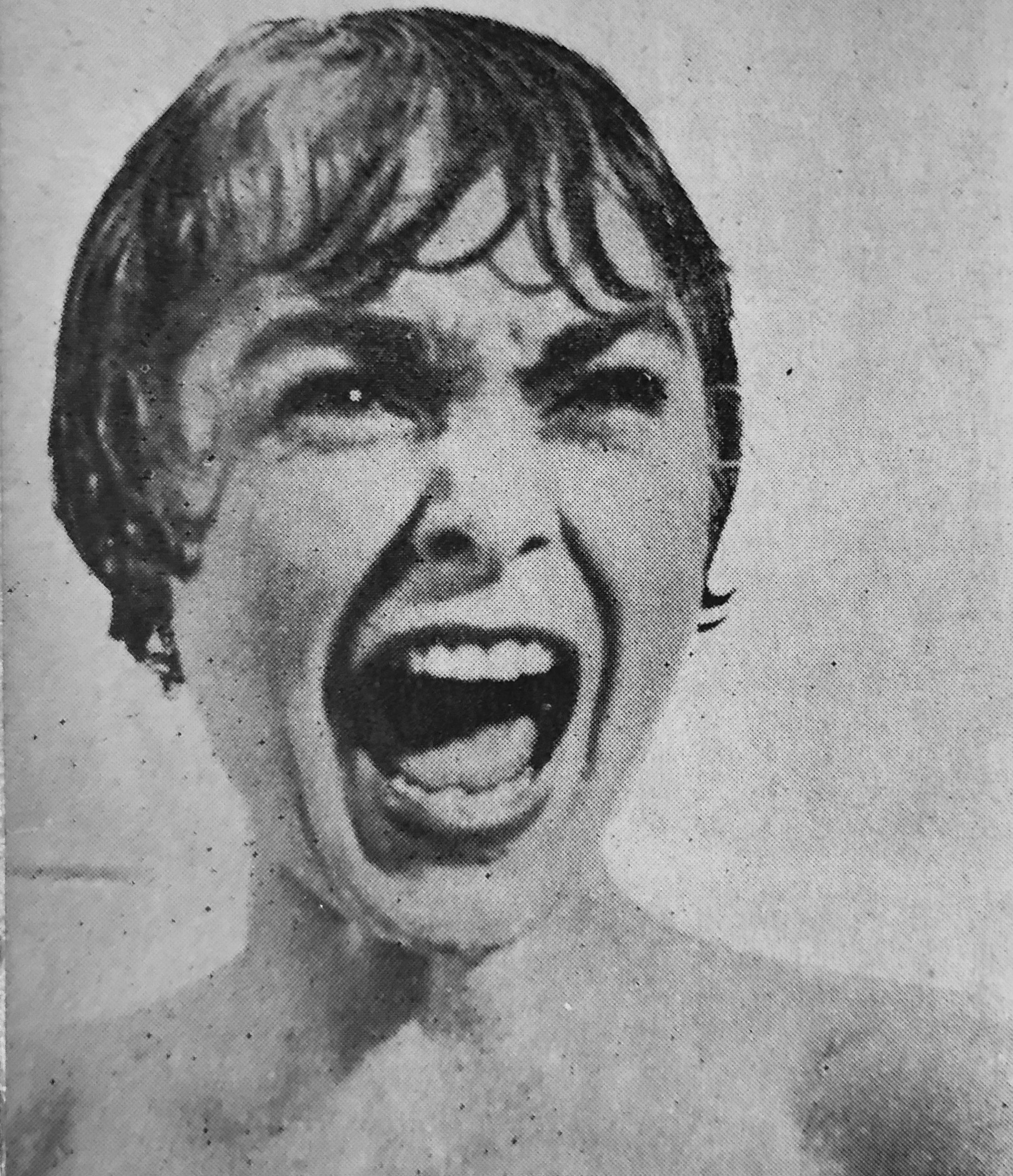

The film was shrouded in secrecy because Hitchcock was worried that he was going to lose everything if the film was not successful. He made sure that nobody told anything about the film while they were making it. He used a special publicity campaign that said the film would be stronger than anything previous witnessed in horror, and that no one would be admitted to the film after the film began. The concept behind this rule was to ensure audiences wouldn’t give away the ending. It was a real cause of excitement for a lot of people watching the film, as they wanted to go see the special secret film that Hitchcock had made. Amongst other things, the film featured the surprise of killing the lead halfway through the film. Nobody expected the graphic violence that Hitchcock provided in the film, including the infamously frightening shower sequence.

Hitchcock instructs Janet Leigh in her performance of the bathroom scene

Until Psycho, there had never been a bathroom sequence in an American film before. Hitchcock was striding into new territory with every sequence in Psycho. The film was a smashing success and audiences around the world raved about Hitchcock’s Psycho. Hitchcock also made a deal with Lou Wasserman who was his agent at the time. Wasserman became involved with a stock deal at universal studios, a small studio that was in a growth phase. Hitchcock generally received a specific payment for a film, but he made a new deal for the distribution of Psycho. He agreed to pay all the cost for the film himself upfront, and all Paramount had to do was distribute the film. Paramount liked the arrangement because the studio didn’t have to pay any cost for the film. Hitchcock paid all costs and then made all revenue off the film, and then his agent Lou Wasserman secured a deal with Hitchcock where he could obtain money for the film in stock. This was ideal as the stock in Universal was growing at a rapid rate.

Until Psycho, there had never been a bathroom sequence in an American film before. Hitchcock was striding into new territory with every sequence in Psycho. The film was a smashing success and audiences around the world raved about Hitchcock’s Psycho. Hitchcock also made a deal with Lou Wasserman who was his agent at the time. Wasserman became involved with a stock deal at universal studios, a small studio that was in a growth phase. Hitchcock generally received a specific payment for a film, but he made a new deal for the distribution of Psycho. He agreed to pay all the cost for the film himself upfront, and all Paramount had to do was distribute the film. Paramount liked the arrangement because the studio didn’t have to pay any cost for the film. Hitchcock paid all costs and then made all revenue off the film, and then his agent Lou Wasserman secured a deal with Hitchcock where he could obtain money for the film in stock. This was ideal as the stock in Universal was growing at a rapid rate.

Overnight, Hitchcock became a very wealthy man. Immediately after he took stock instead of payment for Psycho, Universal had become a major corporate company and Wasserman had become corporate executive with Hitchcock in tow. After the success of Psycho, Hitchcock never had to work again. Psycho paid for the rest of the films that he would make during the decade, and Hitchcock became so wealthy from the stock purchase that he didn’t really feel the need to work much after 1970. Hitchcock’s experience of pre-financing a film helped to change the way films were produced after the sixties. Hitchcock’s methods changed not only production, but the financing of cinema, paving the way for Hollywood and the financing of the later twentieth century.

Key Takeaways

- Hitchcock made the film Psycho on a limited budget, used a television crew, and shot it in black and white with relatively unknown actors.

- Despite Paramount’s original disapproval of the movie, it was a huge success that continues to influence cinema today

- Hitchcock’s strategic financial decisions, including self-financing the film and taking stock in Universal Studios rather than upfront payment, made him incredibly wealthy, and shaped the method of financing still present in Hollywood today.

West Side Story (1961)

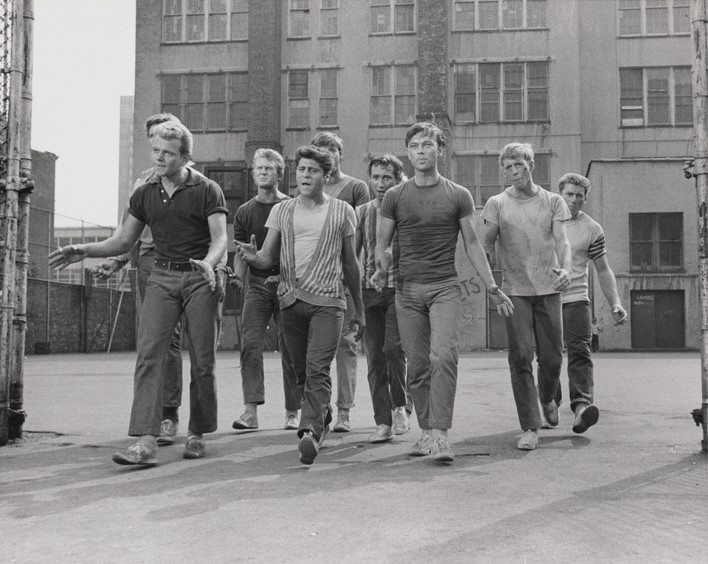

Another influential director of the sixties was Robert Wise whose West Side Story was a major hit. Wise, who had been the engineer for a Citizen Kane in 1941, worked to create a film that was a tableau of New York life. It featured people in the downtown area of New York, with warring gangs of Puerto Ricans, and white street gangs fighting for territory in the town. The film was based on Leonard Bernstein’s story that played on Broadway, which was a musical retelling of Romeo and Juliet. The film takes place in a time when social unrest was brewing, as more immigrants were moving into the United States, especially from Caribbean countries, Europe, Asia, and South America, changing the make-up of the country. The characteristics of social realism in the film struck a chord with a lot of Americans who realized that a lot of Americans in contemporary society were immigrants from new corners of the world. West Side Story was especially a big hit for young audiences, who saw themselves and their diversity reflected in the film. The film was also notable for its introduction of novel music, which was inspired by Jazz and contemporary pop, unlike films from the 1940s and 50s that used conventional pop music.

Another influential director of the sixties was Robert Wise whose West Side Story was a major hit. Wise, who had been the engineer for a Citizen Kane in 1941, worked to create a film that was a tableau of New York life. It featured people in the downtown area of New York, with warring gangs of Puerto Ricans, and white street gangs fighting for territory in the town. The film was based on Leonard Bernstein’s story that played on Broadway, which was a musical retelling of Romeo and Juliet. The film takes place in a time when social unrest was brewing, as more immigrants were moving into the United States, especially from Caribbean countries, Europe, Asia, and South America, changing the make-up of the country. The characteristics of social realism in the film struck a chord with a lot of Americans who realized that a lot of Americans in contemporary society were immigrants from new corners of the world. West Side Story was especially a big hit for young audiences, who saw themselves and their diversity reflected in the film. The film was also notable for its introduction of novel music, which was inspired by Jazz and contemporary pop, unlike films from the 1940s and 50s that used conventional pop music.

Dr. No (1962)

In 1962, Terrence Young directed one of the major hits of the 1960s, during the start of the big space race. It was a film entitled Dr. No, and was based on a novel by Ian Fleming that starred a young Sean Connery, an up-and-coming Scottish actor, who only had minor supporting roles in previous films. Immediately, Sean Connery became the embodiment of Ian Fleming’s James Bond, with his smooth ways with spies, his domination of women, and his muscle with dangerous criminals. The recent James Bond films might have become bigger and better attended, but Dr. No set the template for all future James Bond films. The formula included psychopathic villains, world domination plots, nuclear weapons, cold war intrigue, beautiful women, and Bond’s smooth unshakeable demeanor.

8 and ½ (1963)

International cinema became popular with American audiences, and one of the big hits was filmed by Federico Fellini, about the movie business itself. It was a film about a movie director, played by popular Italian actor, Marcello Mastroianni. The film was entitled 8 ½, and it dealt with the idea of how film directors and Italians in Rome led their lives during the profitable sixties, when the film community was thriving in Italy. In 8 and ½, Fellini shows a society in which everybody is in love with filmmaking and filmmakers are living in a decadent society in which love, sex, booze, and drugs are common-place in everyday life. The films message is that this destructive picture of life is an important part of Italian society, but it’s not the only thing to live for. Society must have deeper values, and Fellini makes the point that filmmaking is only to produce fantasy. He argues that living everyday life is more rewarding than chasing prestige while grappling with endless vices.

20th Century in American Film: Nuclear War

Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 comedy Dr. Strangelove, deals with the idea of nuclear annihilation through a mistaken command that sends an American plane to Moscow to destroy the world, starting World War Three. Kubrick did not believe in the idea of nuclear war and did not think it was something to be worried about, making the film a comedy. There had been a number of films made during about the dangers of nuclear war, and in the 1950s, Roger Corman and other directors made a variety of films about the dangers of nuclear radiation. One example is Roger Corman’s World Without End, which is a low budget science-fiction film, which talks about life after the nuclear apocalypse, in which people have been turned into zombies.

Although Corman’s films were laughable at the time, a lot of people took the idea of nuclear annihilation seriously. In 1959, Stanley Kramer produced a political thriller, On the Beach, based on a popular novel by Neville Shoot. On the Beach deals with the story of the apocalypse. The nuclear war has already happened, radiation is spreading across the earth, and the last survivors in Australia are just waiting for death. An American nuclear submarine reaches the area, and the Australian military begins to hear a radio signal from the US. They send the last submarine to investigate the mysterious sound. When they return to Australia they only have a couple of months left to live. The captain has fallen in love with an Australian girl, but the crew wants to return home to America to die there. The captain, not wishing to abandon his crew agrees to go with them, even though his heart is rooted in Australia. It is a deeply mournful film.

1964 also brought a serious film about nuclear war: Sidney Lumet’s, Fail Safe. Fail Safe refers to the failsafe point. Planes in the strategic air command can only fly so far before they need to return to base and refuel. Beyond the failsafe point, planes cannot return, and they are doomed fall out of the sky. In the film, a transistor fails during a failsafe demonstration for a Senate advisory group on civil defense. One plane gets the go signal to bomb Moscow. The rest of the film is a tense conflict to shoot down the American planes before they can complete their mission. Of course, the American pilots can outthink and outfly the Russian pilots, and it is inevitable that the American plan will succeed leaving the American president the devil’s deal. To prevent a nuclear war, the President agrees to bomb New York. It is a deeply disturbing and terrifying film.

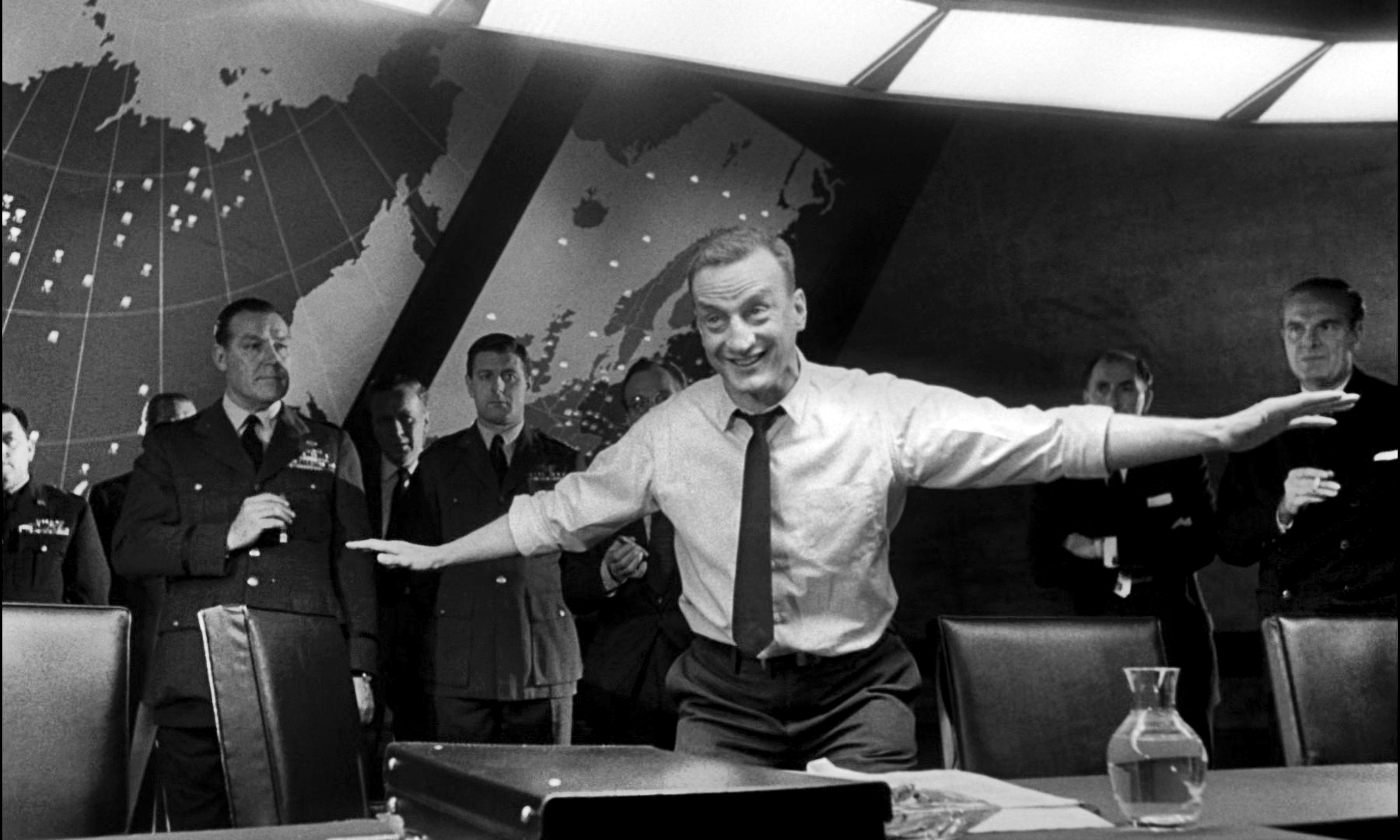

Still from Dr. Strangelove

Stanley Kubrick did not see the idea of nuclear war as frightening. He saw the comical side in people’s ideas of what would happen during a nuclear war. He played on jokes about how there would be air raid shelters where autocrats would take their concubines to repopulate the earth. In his film, a crazed ex Nazi scientist, Dr. Strangelove, told autocrats that his people would rule the world. Dr. Strangelove is played by Peter Sellers, who also plays the president and a British lieutenant. Sellers enjoys himself playing with multiple roles and milks the absurdity of the script and the situation. With support from Sterling Hayden, George C. Scott, and Slim Pickens, the film picks at the absurdity of a winnable nuclear war where millions are fated to die. Pickens has the plum role of riding the nuclear bomb to its destination, a job he approaches with joy and bravado. Although it’s a funny film, it also makes you think about the issue of nuclear war, and how nuclear war would effectively destroy the world.

Key Takeaways

- Several films made during the 1960’s addressed the looming threat of nuclear destruction

- Stanley Kubrick’s, Dr. Strangelove, is a comedic take on the social commentary surrounding a nuclear threat

- Films like Fail Safe, directed by Sidney Lumet, depicted nuclear war in a serious and terrifying tone

A Hard Day’s Night (1964)

One of the most impressive musicals in the 1960s is A Hard Day’s Night featuring The Beatles. The film was created very quickly after the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan’s television in February 1964. The producers of the film wanted to cash in on the group quickly, because nobody thought the Beatles’ popularity would last. The film was put together in March and April, the script was written, and the film began production in May and was released in June 1964.

The entire film from idea, to filming, to editing, to actual release to theaters took less than six months and was a remarkable success for all involved. The Beatles were natural comedians and were very funny in the film. The script was good and gave the Beatles funny biting lines where they could make fun of their working class origins and talk about working class structure in England. The Beatles had the opportunity to play themselves as a group of four working class musicians in the British music industry, at a time when British music was becoming popular across world audiences. The work of Richard Lester, the director, was exceptional. He incorporated a host of cinema techniques including jump cuts, rapid fire editing, close-up shots, black and white film, and musical numbers that seemed to flow naturally from the characters and their situation in the film. In musicals of the 1940s and 50s, people would simply burst into song inappropriately. In A Hard Day’s Night, the Beatles were literally singing like they were a rock group singing a song on TV or in rehearsal, so every musical number in the film seemed like it fit into the natural environment of The Beatles. Audiences were able to watch The Beatles play the songs they were working on as they were filming. It was a very meta-referential film for its time.

Key Takeaways

- When A Hard Day’s Night was originally made, directors filmed it quickly, thinking The Beatles success would only last six-months

- A Hard Day’s Night addresses themes of working class struggles, as well as the lifestyle lived by those in the music industry during the sixties, when British music was beginning to gain popularity in world audiences

- A Hard Day’s Night is different than most musicals, as the musical numbers seem to flow naturally in and out of scenes, due to authentic nature of The Beatles’ relationship to music in real life

Good Bad and the Ugly (1966)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was the third of a trilogy of films created by Italian director, Sergio Leone. The film had elements of Italian cinema including intense close-ups and attractive cinematography. The film was modelled after American Westerns, but with some elements of the Italian cinema layered on top. Leone specialized in longshots, and major vistas, and liked to incorporate fast moving jump cuts interspersed with longer quiet scenes. Many of these films were shot in Spain. Clint Eastwood, who had been an American television star from the Western show, Rawhide, became an international hero in these films, starting with A Fist Full of Dollars, A Few Dollars More, and finally the epic, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. This three-hour Western offered a lively performance from Clint Eastwood, beautiful camerawork, and marvelous iconic and stylistic direction from Leone, a maverick Italian director enamored with American Westerns. The film was popular with young audiences, who liked the idea of the American Western translated into an Italian epic, and it won many awards.

Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Bonnie and Clyde was produced by Robert Towne and talented script writer and director Arthur Penn, starring Warren Beatty, in 1967. It was a brand-new style of film created from the ideas of the French new wave cinema, with Towne, Penn, and Beatty incorporating techniques including jump cuts, hyper subjective portrayals of historical figures, odd filming angles, non-professional actors, and an accentuated use of violence. The film strived to be novel and to tell the story bank robbers in a new and unusual way. The film was in sharp contrast to the way American studio films had previously been made, yet it relied on the Warner Brothers’ history of producing pivotal gangster films. Bonnie and Clyde in real life were two dangerous 1930s outlaws who were violently assassinated by regional police. The depicts them as young people whose crimes reflected the discontent of Americans and American society during the depression.

Warren Beatty in promotional photo for Bonnie and Clyde

The film also implies that the youth’s culture and anger with their elders was a consequence of prohibition. They suggest that prohibition was a mistake that elders inflicted on young people who simply wanted to have fun. A lot of Americans did not like their government and started to change their perceptions to favor criminals. For example, Al Capone was considered a folk hero to a lot of Americans. In Bonnie and Clyde, young rebels fighting banks and the government became heroes, with their wicked ways portrayed as a form of rebellion against an unjust government.

The film portrayed criminals as beautiful and entitled people who were smarter and more aware of society and its impact on them. Their costumes, demeanor, and their ambitions, were nearly revolutionary in fervor, and suggested that Bonnie and Clyde were the real heroes and their ambitions were justified. Society was corrupted before they arrived, and they were left the job of correcting society’s abuses. Warren Beatty became an action star because of the film, and Fay Dunaway became an overnight success. The film also made stars of supporting players, Estelle Parsons, who won an Oscar for best supporting female actress, and Gene Hackman, who played Clyde Barrow’s older brother. Bonnie and Clyde was a riveting and disturbing film, filled with violence, gun play, and a wicked sense of humor about the depression and the state of American society. It serves as a critique on American society, not only in the thirties, but paralleled in the corruption and angst of youth culture in the sixties. The themes of wealth, fun, freedom, being beautiful, and dying young were accentuated by the script, the acting and the advanced camera work.

Promotional photo for Bonnie and Clyde

Key Takeaways

- Bonnie and Clyde was shot with inspiration from French New Wave cinema, which enacted jump cuts and odd camera angles

- The film portrayed bank robbers in a way that had not been seen before in American cinema, giving them redeeming qualities, and using society’s downfalls as an explanation for their crimes

- The film serves as a representation of the youth’s angst during the era in which it was made

20th Century in American Cinema: Addressing Prejudice and Disparity

In the Heat of the Night (1967)

Norman Jewison’s bleak 1967 racial prejudice film, In the Heat of the Night, deals with an African-American policeman from Philadelphia, played by Sidney Poitier. He confronts a racist southern sheriff, played by Rod Steiger, in a drama that deals with prejudice against people of color in the South. It is one of the earliest films to feature a mixed black and white detective team. It is an early film to feature an African-American actor as a leading performer. Here you have Poitier, a star performer, and Steiger, also an Oscar winner, facing off in a taunt drama with an excellent supporting cast, including Warren Oates providing tension. Sydney Poitier had rocketed to fame in 1963 as the star comedy performer and Oscar winner in Lilies of the Field, about an African-American laborer who helps a group of German nuns in the Arizona desert create a church. He had continued his success with a series of films (A Patch of Blue, To Sir With Love) but this was the first film in which he directly dealt with the issue of racial prejudice in the south opposite a white character, who is clearly a victim of his own prejudices.

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

The other major film about prejudice in 1968 is George Romero’s low budget $150,000 film production of Night of the Living Dead, shot in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Romero wanted to address the racial divide in Pittsburgh, where the North side was all African-American people, and on the Southside was all wealthy white people. He used the metaphor of zombies to describe the problem. The film is one of the very first films to have a black protagonist, and certainly one of the first films that has a black protagonist in a horror film. The hero of the film survives the night and protects a white, mentally incompetent girl from the zombies, only to be rewarded by being shot and killed by white hunters in the morning. The film is very a thinly veiled metaphor about racial disharmony in the 1960s

Planet of the Apes (1968)

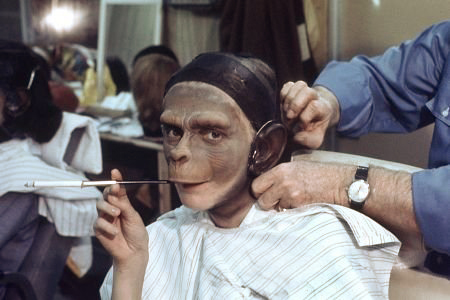

In 1968, science-fiction films began to become popular again, and Planet of the Apes, based on a novel by Pierre Bourdieu (who had also written Bridge in the River Kwai), was produced by Anthony Schaeffer. The film illustrated a group of astronauts that had crash landed on a planet that was run by a group of apes. What they don’t realize at first is that their own society over the years had evolved into a structure in which apes are the dominant species and humans are inferior. Of course, the issue of apes and humans coexisting is a thinly veiled reference to racial disharmony in the era. It is analogous to the political struggles of the civil rights movement in the mid 60s. If you think about it, in 1968, the United States was on fire with race riots across the nation. Martin Luther King had been assassinated, and Robert Kennedy was assassinated not long afterwards. America was filled with violent acts and there was no way that Americans could live in peace and harmony in that environment.

Planet of the Apes behind the scenes photo

Key Takeaways

- Norman Jewison’s, In the Heat of the Night, addresses racial prejudice with his character who is an African-American policeman that confronts a racist sheriff

- Night of the Living Dead by George Romero used the metaphor of zombies to address the racial divide in Pittsburgh

- In Anthony Schaffer’s, Planet of the Apes, the issue of apes and humans coexisting is a thinly veiled reference to racial disharmony during the era

The Producers (1967)

In 1967, Mel Brooks had his first major success as a director with a little film called The Producers. It was a warped comedy about a peculiar subject. The producers are a group from Broadway who decide to make a play that they think will be a sure- fire loser. The goal is that they will have so much insurance on the play, that the play will be sure to make money for them even though the play is doomed to be a failure. The subject to assure a massive failure is a comedy about Adolf Hitler. The play is entitled “Springtime for Hitler in Germany,” and they even created songs portraying Hitler as a musical comedy character. They figure the idea will be so offensive to audiences in New York, many of whom of course would’ve either remembered World War II, might be Jewish, or might have lost family members in the holocaust. They assumed audiences would find the play and subject matter so abominable that the play would close overnight. Despite their best efforts to craft a losing play, the producer played by Gene Wilder, a great comedy actor of the 60s, 70s, and 80s, and Zero Mostel, who had been a great comedy actor in the 50s, 60s, and 70s produced a play that had become a massive hit. People interpreted it as an outrageous comedy and decided not to be offended. They credited the producers as having invented a smart play. The play’s success created all kinds of problems for the producers, because of course they didn’t want to glorify the reign of Hitler and the horrors that he perpetrated on the world, and they didn’t want to profit from a play about Hitler. Their entire scheme was to craft a play that would lose money. The play was very funny, along with the actors themselves. Amusingly, the play was remade on Broadway and later was made into a second film based on that Broadway production. The production moved from film to play back to film.

2001 (1968)

1968 also gave us another science-fiction film that was revolutionary. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, a Space Odyssey was lavishly produced. 2001, a Space Odyssey, was based on a short story by Arthur C. Clark, who was a science fiction writer deeply invested in the realities of science. In the film, the astronauts on board a mission to Jupiter realize that their computer HAL is not acting properly. He’s becoming a sentient being and wants to make decisions without the interference of humans. In the film, the idea of singularity is discussed as well as the concept of an alien species possibly helping humans. There are long passages of beautiful movements in large parts of 2001. The idea of a space opera or a journey through space enhances the film’s sense of reality. The film is also an interesting investigation of man’s destiny, and how men will utilize space travel as a way to evolve the human species. While it is lengthy in duration, the film is beautiful to watch.

Easy Rider (1969)

Easy Rider is one of the pivotal films of 1969, following two motorcycle riding, free spirits who want to avoid the structures of living in a town environment, or living under the laws of people in small towns. Played by Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper, the characters of Easy Rider are simply freewheeling Americans, who want to be left alone to pursue their own course of action. Along the way, they pick up a lawyer played by Jack Nicholson, who also wants to be a free. Along the way they meet hostile and violent police and gangs who threaten them because of their free riding ways. Eventually Nicholson’s character is killed. The performances by Hopper and Nicholson are emblematic of the new style of youth-oriented, American motorcycle films, which discuss the American frontier. It is also part of a new breed of American lifestyle films that discuss cultural priorities. People identified with the film through the character’s lifestyles and the performances of the young actors. Young people who identified with music and the freewheeling lifestyle of the sixties saw the film as an indictment of a repressive society that demanded conformity or death. The film championed alternative American lifestyles, counter cultural lifestyles, music, youth culture, bike riders, and people that didn’t fit comfortably into the pre-assigned categories in American culture. It signaled the birth of the counterculture as a real alternative lifestyle in American society in the 1960s and 70s.

The Seventies

Changes in the film industry included the blockbuster mentality. Films could not simply break even or make just a little money, studios wanted continual massive hits. It was not sufficient for films to make back the investment of money and time, films had to provide big revenue to companies and their investors. This created more pressure on the industry. Many techniques emerged to increase revenue. Some ideas were marketing ideas like sequels. If you make films similar, they should be successful. Another aspect of growing revenue was to use new technology, like Dolby sound, to attract people to theatres and to make the home market enjoy the entertainment on home screens. Some of the techniques used to increase revenue included:

- The sequel

- The Dolby soundtrack

- The videocassette, laserdisc, DVD, and Blu-ray

- The direct-to-video release

- The camcorder

- The computer

- The “all-powerful talent agent”

All of these measures meshed together to encourage a milieu that started developing a new film product. There were science fiction spectacles by George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and others. There were creepy ironic directors like David Lynch, political fables by Spike Lee, and these kinds of film persist into the present day. The seventies changed film marketing and style. Star Wars made science fiction popular for kids, and these became Disneyesque space operas. Disney even bought Lucas’ Star Wars franchise to capitalize off of its success. New films began to resemble the morning serials of the 1940s. Sequels were used to enhance revenue, in other words, the same product was resold. The term for films that kept returning was franchises. In 2021, we had the return of Spiderman with the eighth Spiderman movie, this time copying the ideas from the animated Spiderverse cartoon film made several years ago. Films like Hunger Games, Transformers, Twilight, Harry Potter, Jaws and others depended on franchises to provide revenue for studios. This began when Universal released Jaws in 1975, as this film ushered in an era of blockbuster thrillers.

20th Century in American Film: Technological Advancements of the Seventies

Changes in technology changed how films were viewed and heard. Dolby noise reduction improved the quality of sound. Dolby SVA soundtracks gave the audiences more intense listening experiences, both in the theatre and later home stereo systems. With the auditory improvements of the 70’s, filmmakers began putting more emphasis on curating their soundtracks. You might’ve forgotten the movie, but the soundtrack could still be played to remind audiences of every moment in the film. Star Wars (John Williams), Chariots of Fire (Vangelis), and Thief (Tangerine Dream), often had soundtracks that were as memorable as the films themselves.

Steadicams were used to improve picture quality. Enhanced images contributed to the magic of Forrest Gump, and the special effects of merging different time periods in the film. Into the nineties, the pace of technological change increased. In The Matrix, there was the use of stop-motion photography. The new digital images were referred to as bullet time, because faster shooting times of 60 to 100 to 1000 frames per second could give the effect of stopping time or stopping bullets in motion. By the millennium, theatres had mastered digital projection and could show films with a digital copy on a hard drive. They no longer needed to rely on mechanical film projectors where moving parts or film could break and delay a show.

Many changes erupted in the Hollywood business climate, including a drive for technological films, because technology-based films like Jurassic Park’s photo-realistic dinosaurs were thrilling and novel to audiences. They had never seen anything that big and realistic appearing before. Using the Dolby-sound systems, the thunderous sound of the dinosaurs’ feet seemed astoundingly real. It was like listening to thunder from a movie theatre. But apart from technological films, there were changes in Hollywood deals. Business films were greenlit after a few meetings. If producers could secure bankable stars, directors, and successful ideas, or attach a team to a franchise, marketers believed such films were immune to failure.

Key Takeaways

- During the 70s, Hollywood began to adopt a blockbuster mindset, pressured by investors to generate constant success

- In order to improve the likelihood of box-office success, studios employed methods such as creating sequels and eventually franchises out of one story

- With the introduction of films like Jurassic Park, the demand for technological advancement in studios increased, as audiences were in awe of the newer, more realistic videography

20th Century in American Film: Predicting Success

These predictions were not always foolproof. George Lucas’ much lauded return to directing Star Wars in 1998, The Phantom Menace, was universally panned as a poor movie in the series, but audiences hungry for Star Wars came to see it despite the negative press. Still, sometimes audiences rejected seemingly fool proof projects. For example, in the period between 2015-2020, many Marvel films that were previously part of a successful franchise series floundered, despite positive reviews. Audiences simply were immune to the same thrills after seeing them repeatedly. However, many films have succeeded despite negative press because famous names were attached to it. Several films connected to formerly popular television programs became successful as film projects, simply because audiences already knew the shows and went out of loyalty or the nostalgia appeal. A Peanuts movie, a Simpsons movie, and a South Park movie all benefited from name recognition and loyal audiences who had seen them before on television.

20th Century in American Film: A Change in Content

Seventies and eighties archetypes arrived that helped to transform film. For example, films featuring Supermen: Big strong invulnerable guys that reminded men of how they used to be revered were popular in the era of the seventies and eighties. Films such as Superman, Rambo, Dirty Harry, and Terminator were all successful in that time period. After the chaos and damage from the poor economy in the seventies, slasher films featuring unstoppable demonic killers that nothing can destroy were fashionable with anti-hero murderers like Jason, Freddy Krueger, and Michael Myers. This suggested not only a dysfunction in the economy but a dysfunction of society in general.

Cop Films like Heat, Serpico, and French Connection made cops movie heroes for a generation. This was ironic given that sixties hippies denied cops, called them pigs, and detested authority figures with badges and guns. Some of the popular movie heroes came from films like Lethal Weapon, Dirty Harry, and actors like Al Pacino (Serpico, Godfather, Scarface, Dog Day Afternoon), and Robert DeNiro (Casino, Goodfellas, The Irishmen, The Godfather, and Taxi Driver).

Genres were revived and revered, and audiences flocked to new genres. Films like Jaws, Alien, and Jurassic Park were box office successes, and audiences thrilled to see people chased by big scary monsters. There was a vogue for teen movies, and many were produced by producer and director, John Hughes, including Sixteen Candles, Footloose, Dirty Dancing, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Risky Business, and Home Alone. Heroes, though young, seemed more grown up and cynical. Pop heroes were filled with irony, including Forrest Gump, Harrison Ford (Indiana Jones and Hans Solo), and anti-hero losers like Ed Wood. Some of the biggest franchises that arrived from seventies through the nineties included Lucas and Spielberg’s Indiana Jones, Star Wars, and Jurassic Park films. There have been four Indiana Jones films with a fifth on the way for 2022, nine Star Wars movies and spin offs and cartoons, and five Jurassic Park movies with cartoons and spin offs arriving yearly.

Spielberg and Lucas birthed a new generation of clever young directors. Some of the New offbeat directors included John Carpenter, David Lynch, Tim Burton, John Waters, Jim Jarmusch, and John Badham who directed Dracula, Saturday Night Fever, Blue Thunder, and War Games with young stars Matthew Broderick and Ally Sheedy. War Games was an important film for being one of the first big computer game movies, for bringing paranoia about nuclear war, and for providing action-adventure for the eighties generation and for being a film that aped the Spielbergian style of production and editing.

Key Takeaways

- A change in content where movies featuring characters like Michael Myers and Freddy Krueger gained popularity reflected a dysfunctional society

- Media that emphasized the powerful, hyper-masculine hero archetype gained popularity amongst men in the 70s and 80s

- The introduction of teen movies, like Sixteen Candles, created a new market in the film industry

- Series like Star Wars gained popularity in the 70s, and are still being built on today

20th Century in American Film: New Comedy and an Increase in Violence

New forms of comedy emerged from cynicism and negative perspectives on society. The Coen brothers produced bloody crime movies, and more winsome comedies in the eighties onward, with films like Blood Simple; O, Brother, Where Art Thou?, The Big Lewbowski, and Fargo. Another notable comedic director is Ivan Reitman, who produced Ghostbusters, Dave, Stripes, and Evolution. Spielberg’s protégé and an arch conservative filmmaker Robert Zemeckis, produced Back to the Future with the white Marty McFly teaching Chuck Berry hot play guitar and duck walk, Forrest Gump with Gump never criticizing the Vietnam War, and Flight with a pilot that saves a plane full of people going to jail.

Another new genre was intensely violent films reflecting the outbreak of mass violence in the U. S. including assassinations, daily mass shootings, and violence at schools. Ironically, despite wild high-profile acts of violence in film, the rate of real violence declined in society from the seventies to the millennium, despite it film it being wildly escalated in film. There were films by Oliver Stone (JFK, Doors, Natural Born Killers), Michael Cimino (Deerhunter, Year of the Dragon) Quentin Tarantino (Jackie Brown, Pulp Fiction, Kill Bill, Inglorious Bastards, The Hateful Eight), John Sayles (Roan Anish, Secaucus Seven, Lone Star, Matawan), and James Cameron (Aliens, Terminator, Abyss, Titanic).

There were also filmmakers who became known for their versatility and skill in action and drama including Hong Kong’s John Woo (Broken Arrow, MI2, Face Off, The Killers), Ang Lee (Sense and Sensibility, Ice Storm, The Hulk), the team of Merchant and Ivory (Remains of the Day, Room with a View, Howard’s End), and the versatile Ridley Scott (Alien, The Gucci’s, Gladiator, Hannibal, Black Hawk Down, Matchstick Men, GI Jane, The Martian). From the seventies forward, Hollywood was streaming content at a furious pace.

Key Takeaways

- New comedy of the 70s featured cynical humor and irony

- The Coen brothers, Ivan Reitman, and Robert Zemeckis were all famous for their comedic films

- A new genre of intensely violent films emerged in the seventies, reflecting the rise of assassinations and mass shootings throughout the country

20th Century in American Film: Changes in the United States

In the 1970s, there were three commercial television channels, ABC, CBS, and NBC; there was also PBS, the public broadcasting system. This situation allowed a great deal of unity among the citizens. Why? They were all watching the same things on television. The sitcoms, the dramas, but most of all, the news. This theory of tightly integrated and similar media was known as Fordism. Henry Ford had quipped at his factory in Michigan that you could have any color Ford you wanted, so long as it was black. They only had one paint color because it reduced difficulties in the manufacturing process. Television for nearly twenty years followed a very similar philosophy.

Political disunity in American culture may be traced to the diversity of different stations with widely different content. Recent disunity may be caused to a great extent by the fact that now, we do not all hear or read the same story; therefore, we don’t all tell the same story. There may be different versions of a story, and each is true to different parts of a segmented audience. Today we get our news from media that targets a certain demographic, leaving everyone else to find their own stories from different sources, all of which also target certain demographics.

But disunity was also happening in the 1970s: violent protests against the war in Vietnam, women’s struggle for equal rights, government corruption and the disgrace it caused, leading a president to resign rather than be impeached. In the 1970s, three major events happened in or to the United States including war, a national scandal, and a struggle for equality.

The War

During the seventies, young men were being sent to the other side of the world to kill or be killed. Protests against the war in Vietnam were mounting and continuing through the 1970s; veterans returning from Vietnam organized as Vietnam Veterans Against the War and agitated for an end to the conflict. American citizens were bitterly divided over the war, and much of the division was based on the fact that most of the young soldiers sent there were from poor families and families of color; they had no political power, wealth, or influence to keep them safe.

Those who did enjoy those assets included George W. Bush, who, as a member of the Air National Guard, was assigned to run a political campaign as his military duty; Bill Clinton, who was studying overseas as a Rhodes scholar; and Donald J. Trump, whose doctor got him a deferment from the military draft because he had bone spurs on his heels. Ironically, two of the only politicians who served valiantly, John Kerry, who was wounded decorated and saved men’s lives in Vietnam, and John McCain, who flew bomber missions in Vietnam, was captured and tortured for years during the war, were both soundly defeated by men who either never served or never fought in the war. Such ironies illustrate America’s complicated vision of such wars, which in turn greatly impacts our films and memory of such wars.

High school aged boys were under immense pressure to perform at school, as students whose grade point average fell below a certain level lost their draft deferments and were shipped to Vietnam. The average age of these soldiers was nineteen. The Vietnamese War was also unpopular because the United States was not fighting to protect itself, but to keep the communist Soviet Union from taking over the country of South Vietnam. Fifty-eight thousand, two hundred, and twenty (58,220) young Americans died there for this cause, and those who returned still feel effects of the war; for example, the use of Agent Orange to defoliate the forests of Vietnam, which poisoned many Americans slowly. Some are still dying from its effects.

Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, fell to the communist North Vietnamese on April 30, 1975, and Americans fled Vietnam, taking as many Vietnamese allies as they could fit into their planes and helicopters. Those Vietnamese nationals who had aided the American effort would be killed or “re-educated” under the communist leader Ho Chi Minh, and they tried to get at least their children on the planes and helicopters. The U.S. Embassy in Saigon was the last point of departure: U. S. military helicopters landed on the roof of the building, crowded in as many bodies as they could, and flew them out to waiting U.S. aircraft carriers.

When the carriers’ decks became too crowded with human bodies for the helicopters to land, empty helicopters which were out of fuel were pushed into the ocean to make way for the incoming helicopters. The passion, discord, and insanity of these events are captured in a poem by David Wojahn:

“It’s Only Rock and Roll, but I Like It”:

The Fall of Saigon: The guttural stammer of the chopper blades

Raising arabesques of dust, tearing leaves

From the orange trees lining the Embassy compound; One chopper left, and a CBS cameraman leans

From inside its door, exploiting the artful Mayhem.

Somewhere a radio blares the Stones, “I like it, like it, yes indeed…”

Carts full of files blaze in the yard. Flak-jacketed marines Gunpoint the crowd away.

The overloaded chopper strains and blunders from the roof.

An ice-cream-suited Saigonese drops his briefcase; both hands now cling to the airborne skis.

The camera gets It all: the marine leaning out the copter bay, His fists beating time. Then the hands giving way.

The passion, discord, and insanity of these events are also depicted in Apocalypse Now (1979), directed by Francis Ford Coppola.

Key Takeaways

- American citizens were bitterly divided over the war, much of which was due to the fact that most of the young soldiers sent there were from poor families and families of color

- Wealthy families were able to secure deferments for their children, which postponed their child from being chosen in the draft

- Amongst the privileged youth that secured deferments were Bill Clinton who was studying overseas as a Rhodes scholar; and Donald J. Trump, whose doctor got him a deferment from the military draft because he had bone spurs on his heels

- The Vietnamese War was unpopular because the United States was not fighting to protect itself, but to keep the communist Soviet Union from taking over the country of South Vietnam. Vietnam Veterans are still feeling the effects of war today

The Struggle for Equality

Women were struggling for equal treatment at home and in the workplace. The Women’s Lib movement (as it was called) of the late 1960s and 1970s was the second feminist movement, and it succeeded in raising the awareness of many Americans that women had not gained full citizenship. Even though the feminist activists in the 1970s pushed through an Equal Rights Amendment that had been first introduced in 1923, it was not ratified by enough states and so failed. Its failure “reflected a history of both female participation in politics and exclusion from power” (De Hart 217).

Enthusiasm for women’s rights soon led to several strong female political candidates for national office: Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm made a bid for the Presidency in 1972, and in 1984, Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro was nominated by a major political party as its candidate for Vice President of the United States. Beginning in July 2009, the Equal Rights Amendment has been reintroduced in the House of Representatives every year, until now it needs ratification by only one more state to become law.

Women’s struggles for equal rights are shown in a couple of films as examples: Nine to Five (1980), directed by Colin Higgins, and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), directed by Martin Scorsese.

The National Scandal

A national scandal at the highest levels: an impeachment proceeding resulted in the resignation of a president before he could be tried by the Senate. His resignation itself resulted in the installation of a man in the office of President of the United States who was never elected, but chosen by the disgraced president, Richard M. Nixon. Thus Gerald R. Ford, handpicked by Nixon to replace Nixon’s Vice-President, Spiro Agnew (who had resigned in disgrace over his own illicit deeds), moved up to the Presidency and immediately issued a blanket pardon of Nixon. All the President’s Men (1976), directed by Alan J. Pakala, depicted the events leading up to Nixon’s resignation.

Key Takeaways

- Because the studio system disintegrated in the 1960s, afterwards came the first generation of filmmakers who hadn’t come through the system or via theatre, novels, or television; instead, they had learned film as film

- Raised on watching movies on TV from an early age, they had learned their craft at film school. Coppola went to UCLA, Lucas and Milius to USC, Scorsese to NYU and De Palma to Columbia

- Spielberg created his own movie curriculum by making his own films, which were both technically proficient and steeped in film lore. These directors’ movies are full of allusions to other films, Hitchcock (De Palma), Kurosawa (Milius) and Walt Disney (Spielberg)

- The flourishing creativity and diverse styles of film in the 1960s and 1970s paved the way for movies as they are today

Reading Comprehension

- How did Hollywood originally receive television, and what advantages did television have over film?

- What societal changes are reflected in films like Bonnie and Clyde or Easy Rider? Specifically, how do these films reflect the attitudes of the youth at that time?

- How did Alfred Hitchcock’s, Psycho, impact the way that Hollywood operates today?

- How did movies like Night of the Living Dead use metaphor to address racial disparities during the 1960s?

- How do the movies Fail Safe and Dr. Strangelove differ in terms of their way of addressing the possible outcome of nuclear war?

- What were the three major political/historical events that influenced the course of film in the 70s?

“Copyright © 1960 – United Artists Corporation”., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Universal Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Shamley Productions, Paramount Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Shamley Productions, Paramount Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

宝石社, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Designed by Macario Gómez Quibus. “© Shamley Productions, Inc.”, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(United Artists), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Directed by Stanley Kubrick, distributed by Columbia Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

キネマ旬社報, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Distributed by Warner Bros.-Seven Arts., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Distributed by Warner Bros.-Seven Arts., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Walter Reade Organization, Inc., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Planet of the Apes, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Tribune / SEARCH Foundation, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

SP4 Dennis J. Kurpius, 221st Signal Company (Pic), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Films:

Stone, Oliver. JFK (1991)

Zemeckis, Robert. Back to the Future (1985)

Eastwood, Clint. Sudden Impact (1984)

Readings:

Apocalypse Now. Film clip. Dir. Francis Ford Coppolla. Paramount Pictures,1979. Youtube. youtube.com/ watch?v=Bs9X6NkJDBY.

Glatzer, Robert. Beyond Popcorn: A Critic’s Guide to Looking at Films. Spokane: Eastern Washington UP, 2001.

Green, Willow. “Movie Movements That Defined Cinema: The Movie Brats.” Empire on Line. https://www.empireonline.com/movies/ features/movie-brats-movie-era/

Lewis, Jon. American Film: A History. New York: W. W. Norton, 2008.

Mast, Gerald, and Bruce F. Kawin. A Short History of the Movies. 11th edition. Boston: Longman, 2011.

Steinberg, Randy. “Theatrical Films.” Encyclopedia of International Media and Communications, Donald Johnston, Elsevier Science & Technology, 1st edition, 2003. Credo Reference.