4 The Sound Era

Learning Objectives

- Learn about the history of the Sound Era, and the early technology used to create it.

- Learn about the early issues in sound production.

- Understand how the introduction of sound changed film.

The Sound Era: Early Technology

There is a mistaken belief that many early films were silent, but the truth is that from the beginning of film production, almost all films had a form of sound. While early films did not have a soundtrack and dialogue accompanying them, sound was always a part of film culture from the beginning. Many early films had piano or organ accompaniment simply to emphasize emotional and sensational scenes in the film. Sometimes, narrators would narrate a film, or amateur actors would include dialogue in a film in a live fashion. Early synchronization of film and sound was attempted using phonograph records. When using phonograph records as an accompaniment to a film soundtrack, the sound had to be recorded ahead of time and synchronized properly with the film. If there was a mechanical skip in the record, the sound’s synchronization to the film would be disturbed.

The two principal problems for creating sound film were synchronization of the sound with the frames and amplification of the sound. The motor that drove film projectors was very loud, so being able to hear sound from a scratchy phonograph record with very poor amplification was very difficult. During the early stages of sound film, many people were unable to hear the sound in film because of this. The second problem was synchronization: having the film and the sound play at the same time.

The Amplification Tube

The answer to amplification in film came in the early twentieth century, when Lee De Forest created the first amplification tubes in 1906. RCA and other companies were producing radios, and the tube amplifiers allowed the sound from radios to be heard loudly and clearly. Companies like RCA developed paper cone speakers that gave better sound quality, but the greater issue was amplifying the sound of the radio waves so that it could be heard in the home. The need for a new technology to be able to amplify sound was a difficult obstacle. De Forest developed a vacuum tube that would take the signal from a record and turn up the volume or amplify that sound. The amplification tube pulled electrical power out of the sound and amplifier, using amplitude signals to create more sound, increasing the volume of the original sound. Initially with sound came a good degree of distortion, but over time the engineers developed cleaner sound systems. They found ways to reduce the distortion that came from the amplification tube, and with clearer sound, amplification tubes took off quickly. By the 1920’s, radio receivers had amplification tubes that glowed a bright orange or yellow light with cone speakers that gave beautiful, synchronized sound. The very first radio station that signed on in 1920 was KDKA in Pittsburgh, PA. By the time they had created amplification tubes and cone speakers, it wasn’t long until people would apply that technology to film.

The Vitaphone and The Jazz Singer

The second issue was synchronization. Synchronization was difficult because it was hard to place the sound at the same time as the film. Different methods were used for starting a film at exactly the same moment as a phonograph record. Finally, The Western Electric Company developed a system of linking a phonograph to a film that worked reasonably well. They called this system the Vitaphone system, and they tried in vain to sell the system to several film companies. Film companies rejected it because of the costs and fears that outfitting their theaters with this new system would be expensive. Eventually, in 1926, the Warner Brothers film company bought the Vitaphone system and began to use it in a series of shorts. Finally in 1927, during a big premiere of a popular film by a popular artist Al Jolson, Vitaphone and Warner Brothers decided to make an entire film featuring Vitaphone sound.

The Jazz Singer

This film from 1927 was entitled The Jazz Singer. The Jazz Singer became a big hit for a number of reasons, even though there were still title cards in the film, and much of the film was silent. The sound segments of the film included scenes in which people spoke using microphones and sang on stage. The Jazz Singer was a mixture of title cards, silent film, and sound film put together. It was the first talkie because it was the first film where people physically spoke and sang along with the music in the film. The presence of both live speech and singing made The Jazz Singer a success. The Jazz Singer was popular for other reasons as well, and it was a very controversial film during its time. It told the story of a Jewish family and their son, who they hoped would be a Cantor in the synagogue in the Jewish church. Their son was enamored by Broadway musicals and wished to sing on Broadway for Gentiles, or non-Jews. While he was in rehearsal for a play on Broadway, he fell in love with a non-Jewish girl, which his family disapproved. By the film’s end, his father who is a cantor in the synagogue is very sick, and wishes his son to return home to sing in the church. The son refuses to follow his father’s wishes until he realizes his father is very sick. So while his father is on his deathbed, the young son returns to his family and sings as a Cantor in the church. His father dies happy knowing that his son has returned to the church.

After his father’s death, the son is still infatuated with a non-Jewish girl which upsets the family, as they do not want him to marry outside of their faith. But he was young and headstrong and wished to pursue this relationship with a girl who was not of the Jewish faith. His saving grace was his doting mother who indulged everything he wanted. His mother believed that he should be the man he wants to be, even if it means being a different person than his father and faith desire him to be. She encouraged him. He eventually sings on Broadway, dedicating the song Mammie to his mother, and becomes a famous star. He marries the girl he wishes to marry, and all ends happily with his adoring mother by his side. Despite what seems to be a perfectly wholesome story, the film was extremely controversial. The film dealt with the topics of Jewish people, immigrant people, and a young man who defied both of his parents to have the career of his dreams. The film featured a Jewish man marrying outside his faith, and a mixture of different people from different parts of the world. The film also dealt with immigrants coming into the United States, wanting to integrate into American Society. All of these elements contributed to the film being labeled as highly controversial. These same elements are what created a monumentally popular film that was attractive to a wide range of diverse audiences. The fact that it was in sound only made the film more popular, and people saw the film simply to experience the extravaganza of people singing live on stage in a film. The Jazz Singer was a breakthrough in many ways aside from the fact that it was one of the first synchronized sound films of its era.

Key Takeaways

- Amplification tubes, which allowed sound to be heard inside the home, were created by Lee De Forest in 1906.

- The Vitaphone was a technology created to solve the issue of sound synchronization.

- One of the first films made with Vitaphone technology was The Jazz Singer, which was both controversial and wildly popular.

- Controversial topics from The Jazz Singer include foreign nationality/immigration, disobedience of parental instruction, marriage outside of one’s religion, and societal integration. These topics, while controversial, contributed to the film’s success as it was enjoyed by a wide range of diverse audiences.

The Sound Controversy

Not long after The Jazz Singer debuted, a great controversy arose in the film community as to whether all of the film community would move to sound film, or if sound film would simply be a gimmick to get people into the theaters. The answer was very quick. Within two years or 18 months after The Jazz Singer’s release, despite the high costs of adding speakers, an amplification sound system, and new projectors that ran on a different film speed, the new systems at enormous costs were installed in nearly every theatre in the country by popular demand. The public demanded sound and refused to go to films without sound. By 1928, the public would not patronize silent films, and by 1929 virtually all films being made were sound. By 1930, silent films were dead. The only silent films that made profits in the thirties were films by Chaplin. Chaplin continued to make films that had soundtracks and music made by Chaplin.

Charlie Chaplin and Virginia Cherrill in City Lights

They had live sound in them, but Chaplin generally felt that he could make better films by simply using silent movie methods. Chaplin made City Lights in 1931, Modern Times in 1936, and The Great Dictator in 1940; these were mostly silent films with small elements of sound effects soundtracks, including some dialogue when necessary. For the most part, Chaplin was the only artist during the sound era who could make a silent film that people might still go to see. Sound prevailed very quickly in the field of film technology.

The Sound Era: Movement

One of the challenges in producing sound films was that the actors had to stand near a microphone to be heard. Thus, sound films were made with less movement. In silent films, people could move anywhere they wanted to on the stage, as microphones were not a factor. However, when actors had to stand near a microphone to be heard, movement in films virtually came to a standstill. The talkies became the standstill talkies or the stockies as people jokingly called them.

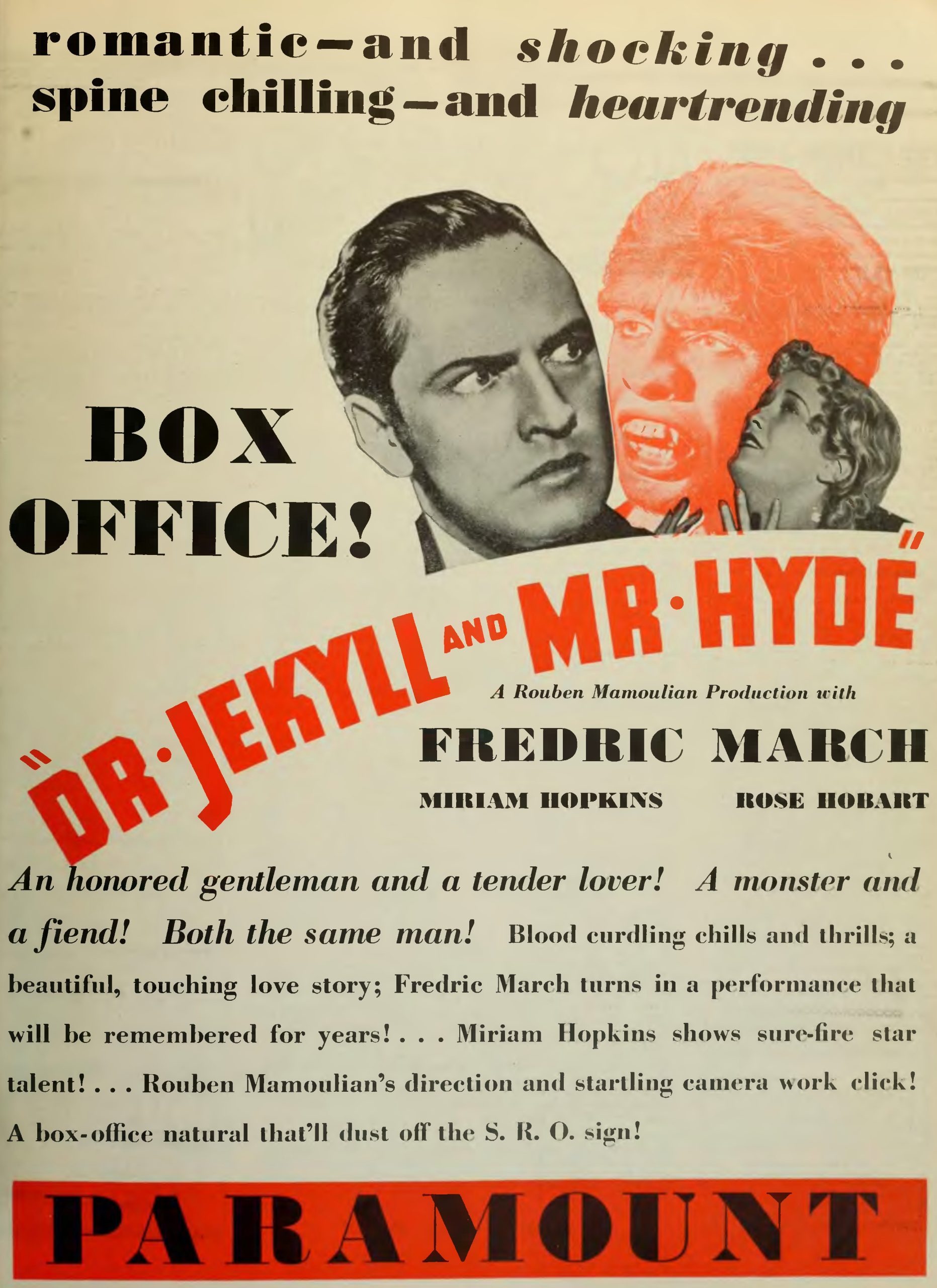

There were several major film directors in Hollywood determined to solve the issue of movement in sound film production. Several different devices were created to solve the difficulties that were created by sound films. One of the first directors to solve the problem of stagnation in sound films and bring movement back to theaters was Rueben Mammalian. Mammalian was the director of the Oscar winning, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932), starring Frederic March, based on the short story by Robert Louis Stevenson.

Mammalian was formerly a Broadway stage director. The film dealt with the issue of how to get sound and movement in the same film by using a solution that Mammalian had seen done on Broadway. On Broadway, film producers knew that people wanted good sound. To achieve this, they designed a sound system with microphones on the stage. Instead of simply putting a single microphone for everyone to group around, they placed different microphones on different sides of the stage, in the center of the stage, and above the stage. They used an audio mixer, which was a device that allowed them to increase the sound on one microphone, and decrease another microphone, so it wasn’t picking up extraneous foot traffic during a scene. Mammalian incorporated the idea of using microphones on various parts of the stage in sound films. In Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, there were microphones placed around the stage so that wherever March moved on the stage, there would be sound that could easily be heard. They began to do postproduction mixing of sound into the film, so that sound that wasn’t recorded at the time the film was made, could be recorded later. Mammalian’s efforts were rewarded in 1932 with the superb attendance at the version of Jekyll and Hyde that he created with March. The sound was very clear and audible, and the actor, March won the Oscar for best performance. Because as Hyde, he could move across the stage making sounds and using dialogue from anywhere.

The other director that worked very hard to make sound successful was Victor Fleming. Fleming was famous for a number of films that he directed, including 1939 Oscar nominees Wizard of Oz that he directed and Gone with the Wind of which he was one of a team of four directors of the film. Fleming actually won the Oscar for best director in 1939 for GWTW, and then in 1940, he made another great film; a second version of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde starring Spencer Tracy and Ingrid Bergman. Victor Fleming had made a lot of movies with western stars and liked making westerns. He also wanted to make western films with live sound. Fleming tackled the issue of movement on a larger scale, as he was determined to record audio during a scene where the actors rode horses. Fleming figured that he could get a quietly running, low-speed truck to be alongside the actors on horses. He used a boom operator with the boom held above the horses. His goal was to record the actors having a conversation while they rode the horses, with the microphone held above them so they could be heard clearly. Between the sound of the noise from the horses and their hooves, the sound of the truck, and the sound of a boom operator coming from the truck, people believed this feat to be impossible. It was previously believed that you could not isolate the sound of the actor’s voices, so you could not record westerns in this manner with live sound. Fleming proved them wrong. He put special baffling in the truck to make to make the sound of the truck’s engine quieter. He also put special baffling around the boom microphone so that it only picked up the sound of the actor’s voices, and not the competing sound of the truck or the horses, and the actors spoke clearly and loudly. Their voices came through loud and clear, making Fleming one of the first and only directors to solve the issue of capturing sound outdoors.

Citizen Kane

One of the other innovators in sound in 1940 was Orson Welles, who had already worked in radio and worked on stage and was making his first movie, Citizen Kane. Welles was amused by the fact that most sound films from the first ten years of sound did not have ceilings in the scenes, because they had to use boom microphones. Welles instructed his technicians on Citizen Kane to develop scenes with sets that actually had ceilings, and people laughed at Welles for this idea. Welles was unphased, as he knew he could place a microphone anywhere and make it work. Welles planted microphones in desks, the sleeves actors, newspapers, or any place on this stage where it might not be seen. He placed enough microphones in every scene where every aspect of every scene could be brilliantly recorded. In one of the most famous scenes at the end of Citizen Kane, the 70-year-old Kane begs his wife, Susan Alexander, not to leave him. She defies him and decides to leave him, and he is left alone in her room. In a rage, he begins to destroy everything in the room, making a lot of noise in the process. Tearing apart wooden cabinets, smashing bottles, throwing things against the wall, tripping over things, tearing up wires, throwing books, and throwing her clothing. The scene is a real mess, but one of the really wonderful things about the scene is the way Welles records the sound, so that you hear the man puffing all the way through as he destroys the room. You hear the actual torment of tearing cabinets out of walls, throwing furniture, and destroying property all the way through the scene. It’s fun to watch because of its marvelous sound design in which you watch a man go berserk in a room. Here sound defines character.

Key Takeaways

- Rueben Mammalian, director of the Oscar winning, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932), used techniques from Broadway to improve range of motion in sound films.

- Victor Fleming, director of The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind, perfected outdoor motion shots with his use of baffling and boom stick microphones.

- Orson Welles used a series of hidden microphones on screen to create never-before-seen action in his iconic film, Citizen Kane.

The Sound Era: Animation and New Technology

Sound also played a role in the enjoyment of animation, and one of the reasons why the Disney Studios became the principal studio for animation in the 1920s, and later, became the most important animation studio in in the world. Today, Walt Disney Enterprises is responsible for about 70% of the films made in the United States. They own Marvel, Fox, Miramax, and many other production companies. Disney became successful despite the problems with animation (it took more time and manpower to make animated films). Disney would take three years to make a film like Snow White, while MGM could make a movie a week, because they had four soundstages constantly at work. However, one of the drawbacks for the other studios was recording sound and recording it well. For once Disney had the upper hand. The animation could be done by the animators, and the sound could be done slowly. Some parts could be integrated in postproduction. They didn’t have to have good sound at the time you were making the pictures; they could add good sound after the pictures were made, which gave Disney a rare advantage. In the process of a film like Snow White, you have three years to find songs, vocalists, and clever dialogue. Disney had access to the best singers, the best composers, and facilities to record and re-record the sound slowly, to make it mix in well with the film. In 1927, Disney Studios was the first studio to deliver a sound cartoon in their debut cartoon with Steamboat Willie, which featured Mickey Mouse in a comedy on a steamboat with animals, an angry boat captain, and lots of goofy examples of sound. The film was extremely successful, and from 1927 until 1937 when they produced Snow White, Disney was on a mission to bring a fully animated sound film to the market. This would entail 90 minutes of sound, and that was a real struggle for Disney. This was true for any studio during that time, simply because of the complexities of making a sound film. Consider these problems with sound, Disney animators had to draw 129,600 drawings per film. All of these had to be planned, scripted, arranged, with foreground and background images, and vocal parts and songs written in and timed. But when Disney delivered Snow White in 1937, it was a massive hit because the voices and the music were beautiful, the animals had wonderful character voices, and the sound blended perfectly with the animated images. Disney didn’t have to worry about the actors having good voices, which is a problem for regular sound films. Because he could pick whatever actor he wanted, he found wonderful voice actors and talented singers.

The struggle to create great sound in film was very complicated and it didn’t end there. Technology moved sound film forward. In the 1940s, the federal government in World War Two realized that records (containing secrets and sensitive information) being transmitted across the Atlantic into France and England were very fragile and could break. They needed a new technology for moving secret messages to the allies in Europe fighting the Germans. They developed a new technology called audio recording tape. Instead of recording on a plastic shellac record, they made audio tapes that were more flexible. One could plunge an audio tape into water and dry it out. You could twist an audio tape or distort it and still have it play, unlike records. It was far more flexible, and it could run alongside celluloid film. Tape made things easier. In the 1940s, the film companies began to realize that if they could run an audio tape through a projector with a pickup at the same time they were running celluloid film, they could do away with Vitaphone records altogether, and they wouldn’t have to play a record with a film anymore. They could integrate the two systems together.

FPS: Frames per second. The standard for sound film was established at 24 frames per second. Silent films ran at 18 frames per second. The reason why silent films have jerky motion when translated to television is that early television projector transfer systems only ran sound film and only could translate film at that speed. Thus, early transfers of silent film to television tapes were recorded at the wrong speed, causing all silent films to look like they are going to0 fast.

Recording with a tape recorder during filming simplified the process of tracking sound with the making of the visual film. By running the film at 24 frames per second, they could achieve higher quality sound. For reference, the silent film era used 18 frames per second. The slower film left very poor sound quality, but when you boosted the speed of the film to 24 frames per second (FPS), you received a higher quality sound signal. That is the fascinating story of how World War Two enhanced sound film.

Key Takeaways

- Disney had a distinct advantage over MGM during the early stages of the Sound Era, and they were able to perfect sound in post-production.

- The invention of tape during WWII led to improvements in sound film, causing the Vitaphone to be obsolete.

Reading Comprehension

- How was the issue of sound synchronization solved?

- What was the cultural significance/ controversy behind The Jazz Singer?

- How did Rueben Mammalian, Victor Fleming, and Orson Welles each contribute to the improvement of sound film?

- What role did the introduction of sound have in cementing Disney as the predominant film studio in the United States?

The Sound Era [NEW TAB]

Transition to Sound [NEW TAB]

The History of Sound [NEW TAB]

The Jazz Singer (Synchronized Speech) [NEW TAB]

Still from City Lights, produced by the film studio United Artists., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

University of Washington, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

RKO Radio Pictures, still photographer Alexander Kahle, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

New York, Wid’s Films and Film Folks, Inc., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons