10 Film Noir

Learning Objectives

- Learn about how German occupation impacted French cinema

- Understand the common elements and themes featured in Film Noir

- Understand the perspectives and social issues represented during this era of film

Film Noir: The Impact of German Occupation

Film noir was a style of film that erupted after the chaos of World War Two. Noir was characterized as a group of films that featured themes of criminal enterprises, mystery, police, crimes, and larceny. Qualities of these films were dark and mysterious settings, dark lighting, shadow, shades and blinds, nighttime scenes, and the use of weather and atmosphere to characterize events. These films are characterized by a cynical view of human nature. Women are particularly problematic, with many women not considered trustworthy or painted as out right dangerous. The term, “femme fatale,” was coined to describe women in this genre. Noirs often portrayed fate as capricious or working against the protagonists of the film. The worldview of film noir was not only cynical but dark. People lied, betrayed, and disappointed those around them. Women were untrustworthy. Friends were not friendly. It was a world in which community or friendship did not matter, and fate or other forces could intervene and bring characters to ruin. Noir was often fatalistic, with the end result of their storylines being death, crime, murder, betrayal, unhappiness, and disappointment.

Noir as a term arrived from French critics who saw American films after World War Two. France had been captured by the Germans in the early days of World War Two and was occupied from 1940 until 1945. Later, they were freed from German rule and captivity by the allies, and the Germans were driven out of Paris and out of Northern France. French film critics had been watching American films through 1939, and had seen the studio system in 1939 at its zenith in films like Gone with the Wind, Of Mice and Men, Stagecoach, Wizard of Oz, Son of Frankenstein, Hound the Baskervilles Dark Victory, Ninotchka, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Love Affair, and a host of other brilliant and wonderfully realized films from the American studio system. But once Germany occupied the country in 1940, the Germans cut off the French critics from all American films for five years as part of their propaganda efforts to promote German society and criticize the allies and the other Western powers. When the allies returned and freed France in 1945, French critics gained access to American films for the first time in five years.

What they witnessed was a complete change in the style of American film from 1939 to 1945. American films had changed, becoming darker, grittier, and more cynical because of the horrors of war, the depression, the deprivation of the American people, and the poverty that had swept the United States and the world. The darkness of the depression years followed by the sacrifices of a world war transformed film makers in Hollywood. They moved towards a pessimistic, more grim style of film that reflected the feelings of the American people. Americans had seen corruption in their own country, had learned to sometimes fear authority figures such as the clergy and the police, and were very concerned about the shape of the world following the war, including the incursion of communism into Eastern Europe.

French critics referred to these new films as film noir or, “black film,” because they were very dark in tone, and disturbing in their content. Most of the films of the noir era were crime, mystery, or suspense films in which criminal elements or criminals were the focus of the film. Through the lens of this genre, the police were no longer in charge, the clergy were no longer trustworthy, specifically women were no longer to be trusted, and the world was a darker and more corrupt place.

Key Takeaways

- Film Noir was coined after the end of World War Two, when French film critics were exposed to American film for the first time in five years following German occupation

- The genre featured dark, shadowy cinematography, while presenting themes that addressed topics of crime, mystery, mistrust, and corruption.

- The term “femme fatale,” was also coined during this era, as many noirs employed tropes of evil, manipulative, and dangerous women.

Qualities of Film Noir

Within every film noir is the antihero protagonist, who has either done something wrong, or is a victim of fate. He can’t win no matter what. Humphrey Bogart in High Sierra is an example of this archetype; his character is a criminal who finds himself in a cabin up in the woods, surrounded by the police with no way to escape.

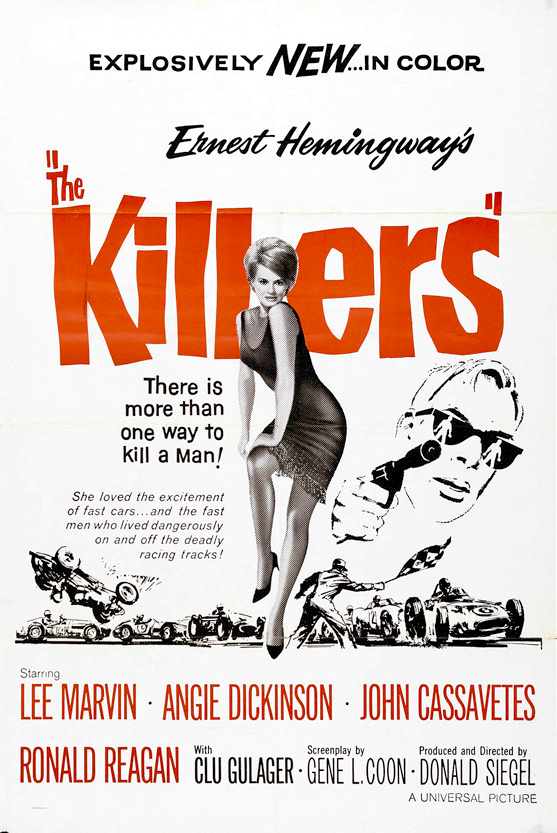

In many film noirs there is an evil, lying woman. In 1964’s remake of Earnest Hemingway’s, The Killers, there is Angie Dickenson, who pretends to be in love with John Cassavetes to trick him into helping her and her boyfriend (Ronald Reagan) steal money. In the end, the killer (Lee Marvin) tracks the money to the girl. She proclaims, “I had nothing to do with it, it was all his (the boyfriend’s) idea. Marvin, who has been shot by Reagan and is dying and doesn’t believe her saying, “lady I don’t have the time,” and shoots her. This is a common fate for a film noir heroine. Film noir usually featured women of low morality who are only interested in using men to get what they want, eventually leading to a man’s demise.

Poster for the Movie, The Killers

Another aspect of film noir is schematic plotting that provides a template to the crimes and themes. Because many noirs were shot on the cheap, a hallmark became dark, simple, and atmospheric lighting, where scenes are infused with high contrast darks and lights. Shadows, fog, mist, and rain made up for extensive sets. Most noirs featured the war and often displayed themes of post-war disillusionment.

Many of the characters in film noir had fought in the war and believed they would come home to glory and good jobs, and what they found after the war was that 4Fs (disqualified for fighting because of a disability), had found the best jobs, and other vets were left with minimal employment. Noirs are peppered with characters who experience psychological angst and fear, much of it promoted by years in the military. In their world, things were not fair, and their psyches were damaged by the abuses of war and excessive violence.

Film Noir: Influential Films

The first film noir was 1945’s Detour, by Delmer Davies. The film is fatalistic and pessimistic, seeming almost like a surreal waking nightmare. It has many of the qualities of noir. The hero of the film, Al, is a vet from World War Two. He is pictured playing piano in a seedy bar with his girlfriend, who wants to move West. When she decides to go to Los Angeles to become successful, he follows her there. He hitchhikes and is a picked up by a man named Haskell. Al is waylaid by a series of events that destroy his happiness. He takes over driving for Haskell who falls asleep. At a stop, Al finds out that Haskell has died. He meets a woman that needs a ride at a truck stop. Her name is Vera. She recognizes the car and tells Al she knows he stole the car, because she caught a ride with Haskell in that same car the day before. She coaxes Al to take her to LA and to help her with her criminal acts. Al, trapped, takes her to Los Angeles. Upon their arrival, she immediately gets drunk and threatens to call the police on him. He tries to grab the phone cord from her. She runs to another room and locks the door. In her drunken state she wraps the cord around her neck. Unknown to Al, his pulling on the cord strangles Vera. At a truck stop, Al is picked up by the police, and he assumes that it must be fate that wants him dead. Fate, evil women, and bad luck conspire to make this a classic noir story.

Promotional Photo for Detour, 1945

Alfred Hitchcock is one of the most notable directors during this era of film. Hitchcock specialized in this new style of suspense film during the film noir era. Hitchcock had a great influence over world filmmaking, including the French new wave. He was highly intelligent, and able to make clever and dark films within the shelter of the studio system. Hitchcock was able to assert such control from studios because he was clever, literate, budget conscious, and made mostly popular films that pleased audiences. He also knew how to harness the media. He started several mystery magazines that spread the Hitchcock name and brand, and he quickly grasped the power of television and produced his own television program for ten years, making him the most well-known film director in the United States.

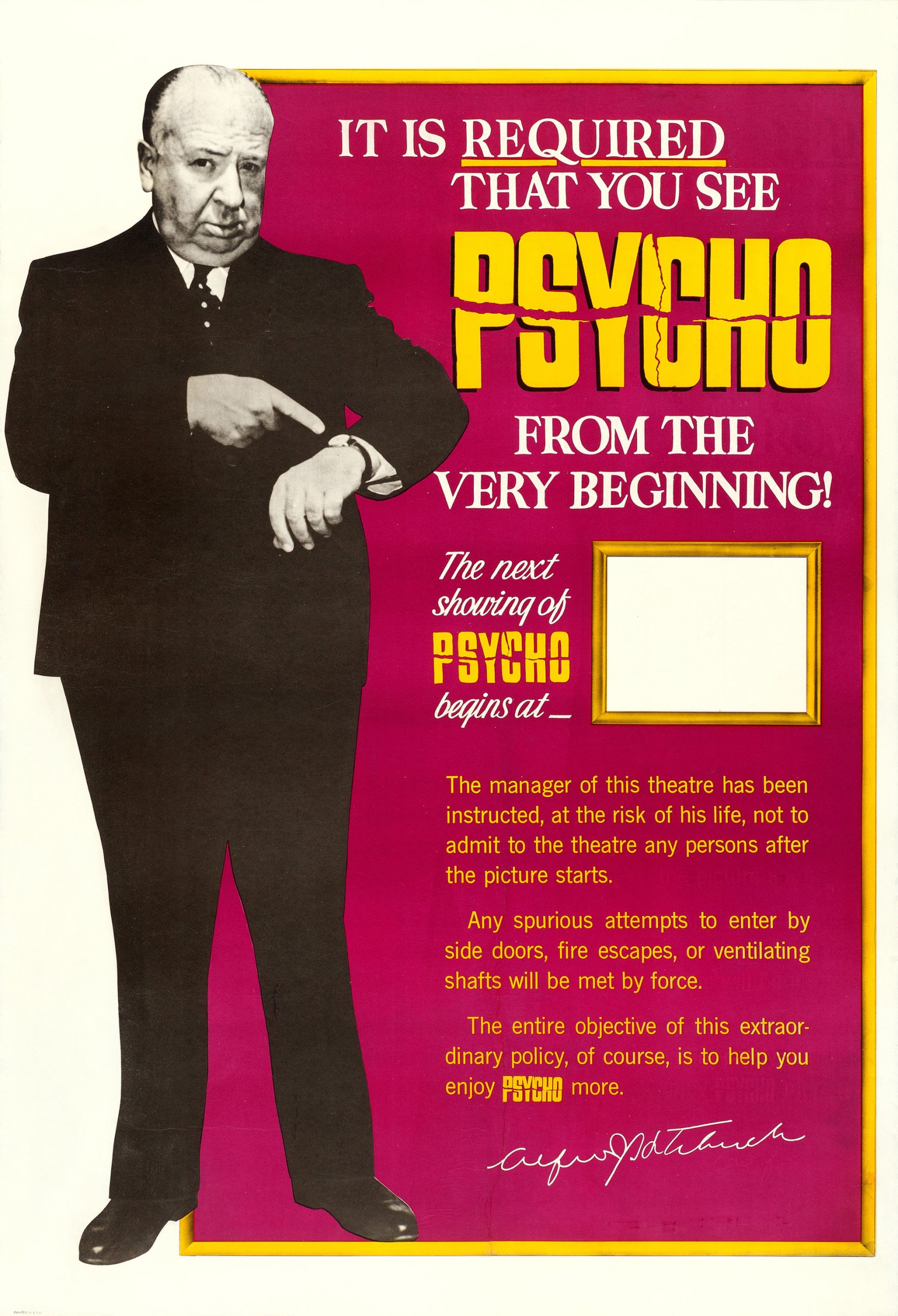

Hitchcock started his United States tenure with a strong hit film, Rebecca. Rebecca was a popular novel by mystery writer Daphne Du Maurier, starring two young attractive actors, Laurence Olivier, and Joan Fontaine. It won the Academy Award for best picture in 1940. He directed Shadow of Doubt in 1942, co-written by Thornton Wilder who had written the stage hit, Our Town. In 1946, Hitchcock paired with Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman, two of Hollywood’s top stars, for a spy thriller called Notorious. Hitchcock was a dominant force in the fifties creating a string of crime thrillers starting with Stage Fright in 1950, Strangers on a Train in 1951, Rear Window in 1952, Dial M for Murder, The Man who Knew too Much in 1955, The Trouble with Harry 1956, Vertigo 1957, The Wrong Man 1958, and North by Northwest in 1959. In that ten-year era, Hitchcock became America’s most subversive filmmaker, making films about the dark corners of American Society. He toyed with storylines where corruption might dwell without anyone actually knowing it existed. The high point of Hitchcock’s cynical view of America was Psycho, a dark fairy tale of sex, perversion, cross dressing, serial murder, and psychosis. The film takes a simple plot of a thief who is killed by a maniac who runs a motel and transforms that into a telescoped view of American culture.

Poster for Alfred Hitchcock’s, Psycho

Film noir also managed to incorporate humor amidst its serious nature. For example, in Dial M for Murder, the husband is in deep financial trouble and wants to murder his wealthy wife. He hires a man to do it. The assassin attempts to kill her but bungles the job and dies in the process. Hitchcock can’t avoid employing a joke when the husband calls to set the murder in motion, and to his surprise his wife answers, saying, “someone tried to kill me!” The husband’s responds, “did he get away?” The darkly comical aspects of noir make the films amusing despite the macabre subject matter.

Drive-In Flyer for Dial M for Murder

Key Takeaways

- Alfred Hitchcock was one of the most influential directors in the Film Noir genre, dominating the film industry over a span of 10 years.

- Hitchcock had much creative freedom and power within the studio system, as he was intelligent, budget conscious, and was largely successful in pleasing audiences

- Hitchcock mixed humor into his film, Dial M for Murder, adding amusing elements between the otherwise dark subject matter

Film noirs were sociological in nature, dealing issues of social justice. In The Third Man, Harry Lime is a black marketer. His dilemma is that criminality is what society needs to get the products they want; under these pretenses, is he really a criminal? In Detour, Al is just trying to get to his girlfriend, and fate seems out to derail his plans. In The Asphalt Jungle, the robbers don’t mean to hurt anyone and planned well, but a security guard gets in their way. His inconvenient death ruins their plans. In Crossfire, a group of servicemen are implicated in killing a Jewish man. The film poses the question of whether it was rage or antisemitism driving the men to murder.

Probably one of the earliest examples of noir was John Houston’s The Maltese Falcon in 1941. This film based on a Dashiell Hammett novel tells the story of a detective, Sam Spade, who meets a woman and a series of criminals who try to get Spade to help them locate a fabled valuable Maltese Falcon.

Stills from The Maltese Falcon Trailer

The Falcon is supposedly a black bird covering a priceless gold statue. They killed Spade’s partner Archer to get the bird. Virtually everyone is lying to Spade, and even Spade indulges in a little play acting with the criminals. By the end of the film, Spade wants the object gone, so that the murder and larceny surrounding the object stops. In the end we discover that the Falcon is just a cheap statue covered in black paint. When all are arrested and all is revealed, the police famously ask Spade, ‘What is it?’ Bogart famously responds, ‘It’s the stuff that dreams are made of.’ Though pre-noir in time period, Falcon has the noir viewpoint of fatalism, deception and a pessimistic view of human nature.

View the movie trailer for The Maltese Falcon here.

Another noir from 1944 was Laura, where a detective investigates the murder of a beautiful but evil femme fatale. There’s a series of men who think she loved them, but we learn she was willful, calculating, and used everyone in her path. This film focuses on the massive mistrust of women, which was probably a response to World War Two and the growing power of women in the marketplace. Many men returned from the war to find women had taken their jobs. This fueled resentment towards women. The film in a way is about misogyny, but the lying and deception suggests a culture of criminal intent and suspicion.

In The Blue Dahlia from 1946, starring Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake, a sailor comes back from the war and discovers that his wife has been unfaithful, and that his child has died due to his wife’s alcoholism. Again, the film critiques relationships, faith, and American institutions like marriage. Again, many men returned from the war to find their wives remarried.

In 1958, Orson Welles made Touch of Evil, one of the last of the film noirs. In the film, a corrupt policeman, Hank Quinlan, utilizes his corrupt police force to make money from people at the border of Mexico and the United States. The film emphasized the idea that this interstitial world between two clear places with clear laws is the amongst the most dangerous places on earth. The film suggests that borders are liminal places where new systems can be viewed, and new ways of seeing the world can be revealed.

Film noirs didn’t end in the 1960’s. The last noirs of the era may have been Touch of Evil or Hitchcock’s Psycho, but many film noirs were created into the later decades of the twentieth century. Revamped noir of the late century was dubbed neo-noir, incorporating younger players, more tech, and themes of corruption in governments and corporations introduced to the genre. One example is David Lynch’s Blue Velvet in 1987, starring Kyle McLaughlin, Isabella Rossellini, Dennis Hopper, and Laura Dern, it dealt with criminal conspiracies in small town America. More recent examples of neo-noir are Quentin Tarantino’s films including Pulp Fiction, Reservoir Dogs, True Romance, and Kill Bill, which all feature depictions of the rotten underbellies of society, and strong criminal elements. Today, the influence of the noir era is still thriving in feature films, television melodramas, and popular police dramas.

Reading Comprehension

- What perceptions of women after World War Two are represented in the film noir genre?

- What historical events surrounded the introduction of film noir in America and France?

- What themes are common in the film noir style, and how do they reflect changes in society after World War Two?

- What messages do films like The Maltese Falcon and Detour provide about humanity?

Universal Pictures, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Detour, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Warner Bros., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Paramount Pictures., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Terms

Film Noir: noir was a style of film produced from 1945-60 that focused on criminal activity, fatalism, femme fatales, and interacted with mystery and suspense films.

Femme Fatale: A French term describing women of low moral character who bring noir heroes to ruin.

Films:

Houston, John: The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Hitchcock, Alfred: Psycho (1960)

Welles, Orson: Touch of Evil (1958)