6 Chapter 6: Building Networks and Teams

Chapter 6 Introduction[1]

U.S. Route 1 in southern Florida connects 43 islands of the Florida Keys via 42 bridges. It is a bidirectional economic path from the U.S. mainland to its endpoint at Key West and for all points in between. Without the bridges it provides, residents, workers, and tourists would be required to ferry to their destinations, sacrificing time, money, economic efficiency, market productivity, and recreation. The bridges ensure an unimpeded flow of economic activities that benefit residents and visitors, increasing tourism across the entire state, and ensuring Key West is not economically and socially isolated.

Every entrepreneur can learn a few lessons from this highway. First, independent market players are stronger and more stable when connected to other independent market players. Second, connections are not always easy to establish. The idea of connecting all of the keys met resistance, and engineers had to solve many challenges. Third, you must be prepared to repair connections whenever they are severed. A hurricane destroyed the original railroad that connected the islands, but replacing it with an automobile highway was a major improvement. Other lessons are that benefits should outweigh costs, and that it takes time to build new connections: The original railroad took seven years to build. Costs of ongoing repair and maintenance have exceeded $1.8 billion[2] (adjusted for inflation) but produced $2.7 billion in annual economic activity for 2017.[3] Today, no one in Florida would dream of doing without the highway.

How are businesses similar to Key West? Every business includes people who produce goods and services for customers to purchase. In turn, businesses and those who work for them need to consume the products and services provided by their own vendors. Finding and establishing relationships with vendors and customers, in addition to the support of community organizations and educational resources, facilitates the exchange of information, products, and services. The connection between a business and its vendors or its customers makes up a network.

Building and Connecting to Networks

When you begin thinking about your new and exciting entrepreneurial venture, you may feel somewhat isolated. No matter which way you turn, you eventually come to the end of your limited community, and what you have is not enough. You can either sit on the beach and dream about what could be or commence working on building personal and professional connections to broaden your scope and improve the depth of relationships with those individuals who will assist you in becoming a successful entrepreneur. Now is the time to start building bridges and connecting yourself with the greater business community. Networking is about building bridges.

For an entrepreneur, networking is finding and establishing relationships with business professionals with whom you can exchange information, ideas, and products; more importantly, you can claim these networks as trusted business colleagues. Be ready to use the networks you already have. Be intentional in seeking out established business professionals in your local chamber of commerce or at SCORE (see the below). Position yourself to contribute to the larger community. Be active in expanding your sphere of influence.

A good way to get started is to begin brainstorming a list of people who can help you along the entrepreneurial path. These potential trusted advisors will be beneficial to you as you develop your idea and start your business. In these early stages, you will encounter challenges and obstacles in many areas. Having a “go-to” list of dependable consultants can help you find solutions, reduce mistakes, and hasten your success in your new business. Anyone can be on that list—don’t exclude anyone, no matter how unlikely it seems that you will need their expertise. People you already know have knowledge and skills. They can be a valuable resource.

On the other hand, you too have knowledge and skills. You too can be a valuable resource. That is why you are starting your own business or developing a new product. Begin connecting with people who need you, perhaps even people who need you more than you currently need them. Present yourself as the expert, not the salesperson to be avoided at all costs. Become known as the “go-to” person: the person others will seek out and put on their list of experts. When you become respected as the professional expert, success will follow.

We begin developing personal connections—relationships with other people—early in our lives. (Later in life, these connections become our networks.) Typically, the first social groups we join are family, neighbors, and schoolmates. Playing with siblings and cousins, and learning to meet new friends in the neighborhood and at elementary school help us develop the social skills that we will need later in life when we meet and work with others in the professional world. As you enter adulthood, social connections that you establish and nurture become more complex and have longer-lasting benefits. You may establish some of those lifelong personal connections during your college years or perhaps in your first “big” job.

Making Networking Happen[4]

Networks create value, but networking takes real work. Beyond that obvious point, accept that networking is one of the most important requirements of a leadership role. To overcome any qualms about it, identify a person you respect who networks effectively and ethically. Observe how he or she uses networks to accomplish goals. You probably will also have to reallocate your time. This means becoming a master at the art of delegation, to liberate time you can then spend on cultivating networks.

Building a network obviously means that you need to establish connections. Create reasons for interacting with people outside your function or organization; for instance, by taking advantage of social interests to set the stage for addressing strategic concerns. Ibarra and Hunter found that personal networking will not help a manager through the leadership transition unless he or she learns how to bring those connections to bear on organizational strategy. In “Guy Kawasaki’s Guide to Networking through LinkedIn” (see below), you are introduced to a number of network growth strategies using that powerful Web-based tool.

Finally, remind yourself that networking requires you to apply the principle of reciprocity. That is, give and take continually—though a useful mantra in networking is “give, give, give.” Don’t wait until you really need something bad to ask for a favor from a network member. Instead, take every opportunity to give to—and receive from—people in your networks, regardless of whether you need help.

Go Deeper: Guy Kawasaki’s Guide to Networking through LinkedIn

LinkedIn (http://www.Linkedin.com) is the top business social networking site. With more than 30 million members by the end of 2008, its membership dwarfs that of the second-largest business networking site, Plaxo. LinkedIn is an online network of experienced professionals from around the world representing 150 industries (LinkedIn, 2008). Yet, it’s still a tool that is underutilized, so entrepreneur Guy Kawasaki compiled a list of ways to increase the value of LinkedIn (Guy Kawasaki, 2008). Some of Kawasaki’s key points are summarized here that can help you develop the strategic side of your social network (though it will help you with job searches as well):

- Increase your visibility: By adding connections, you increase the likelihood that people will see your profile first when they’re searching for someone to hire or do business with. In addition to appearing at the top of search results, people would much rather work with people who their friends know and trust.

- Improve your connectability: Most new users put only their current company in their profile. By doing so, they severely limit their ability to connect with people. You should fill out your profile like it’s a resume, so include past companies, education, affiliations, and activities. You can also include a link to your profile as part of an e-mail signature. The added benefit is that the link enables people to see all your credentials.

- Perform blind, “reverse,” and company reference checks:Use LinkedIn’s reference check tool to input a company name and the years the person worked at the company to search for references. Your search will find the people who worked at the company during the same time period. Since references provided by a candidate will generally be glowing, this is a good way to get more balanced data.

- Make your interview go more smoothly: You can use LinkedIn to find people that you’re meeting. Knowing that you went to the same school, play hockey, or share acquaintances is better than an awkward silence after, “I’m doing fine, thank you.”

Campus Connections

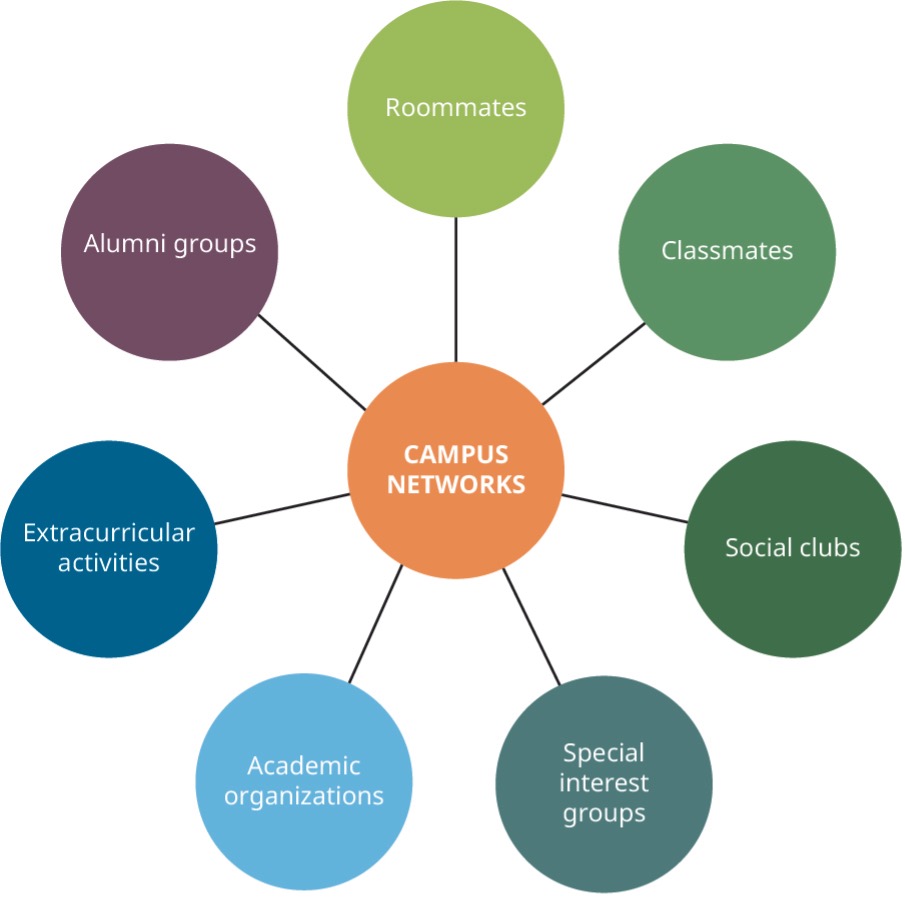

Chances to meet and work with new people abound on college campuses. During your college years, you will have many opportunities to make connections with new people (see Figure 6.1). Taking advantage of these opportunities allows you to perfect your skills in initiating and developing new and even lifetime connections. You can establish new friendships with roommates, classmates, social club members, special interest groups, academic organizations, competitive and intramural athletic teams, and many others. All of these groups not only encourage new social relationships but also foster opportunities for developing and improving leadership skills.

Figure 6.1: Social networking opportunities through your university

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license

Your college or university is usually where you make the transition from student to professional. One method of learning to become a professional is through membership and leadership roles in academic or professional clubs. Leadership positions usually rotate annually. Academic clubs are formed around disciplines, departments, or professions. Professors, alumni, or industry professionals serve as sponsors and may provide connections to other industry professionals. Members learn the value of being active participants, discussing relevant topics. Fundraising or other special activities provide opportunities for developing leadership and organizational skills. Friendships and personal connections made in an academic club may become lifelong professional connections.

Honor societies are another type of academically oriented group, established to recognize the outstanding academic performance of students who have achieved a specific grade point average. Membership in an honor society brings with it the prestige of membership, opportunities for leadership roles, and access to professionals in many industries. Some honor societies offer scholarships for future studies in graduate school or study-abroad programs, which introduce members to students from other universities and countries with similar backgrounds and interests. Some honor societies open doors to conference memberships and presentations, and important access to other industry professionals.

Another type of collegiate organization is the special interest group. These groups may focus on social causes, promote and advance interests in the arts or other hobbies, or encourage participation in political, religious, or athletic events. Students from all disciplines and social backgrounds join special interest clubs. With such a broad spectrum of members, you have the opportunity to learn from many people from multiple backgrounds, expand your self-development, learn how to work with people who have different viewpoints, and potentially establish firm personal relationships.

Some clubs offer members the opportunity to perform or showcase their talent in a more relaxed and supportive atmosphere, or are centered around a personal interest. For example, a drama club for students not majoring in theater can offer a forum for participating in musicals and plays without the rigor demanded by the more structured academic program. Other groups that bring in nonacademic members include choral groups, visual arts gatherings, astronomy clubs, and gaming societies. These groups provide opportunities for the maturation and perfection of the interpersonal skills you need for success in the professional world. You can develop key interpersonal attributes among friends and colleagues while enjoying a common activity or interest.

Social clubs—sororities for women and fraternities for men—provide other opportunities to expand your circle of friends, as these organizations focus on social activities. Although many social clubs concentrate strictly on “get-together” activities, you can learn and perfect acceptable public-protocol behaviors at formal events as well as mastering skills in organizational negotiations and compromise. A few colleges and universities are beginning to formalize clubs for online students, including access to and membership in campus-based Greek life. One of the first online Greek clubs is Theta Omega Gamma, founded in 2009 at the Florida Institute of Technology.

College groups have high turnover rates in their membership and involvement. This can make it easier for you to learn and perfect the skills necessary for establishing social and professional connections through constant repetition of introducing yourself to new people, learning their backgrounds, and describing your own. Learning how to introduce yourself and become acquainted with strangers is a soft skill that you can learn more easily early in life than in later years, and knowing how to develop a personal relationship with others will benefit you for many years to come. One unintended benefit is that mistakes can be quickly forgotten. If you make a social blunder one semester, many in the group will soon forget your faux pas, and new members will never be aware of it.

Perhaps the largest university club is one whose membership extends beyond graduation—the alumni association. Membership in alumni associations is higher among students who earned an undergraduate degree than among those with a graduate degree. Furthermore, members of the alumni association are more dedicated and loyal to their alma mater than nonmembers. Because of their commitment to past and current students, members of alumni associations have an automatic connection to other members. Loyalty is an important characteristic of active members of the alumni association, so bonding with them links you to established professionals who can help you in your new business. One way to connect with alumni is through LinkedIn, a social network of business professionals.

For many students, the campus setting—either traditional or virtual—is one of the earliest multifaceted environments to which you will belong. Learning how to maneuver on the college campus and within the parameters of university culture prepares you for your future professional and personal environments.

Nontraditional and virtual students also can benefit from their college campus experience. These students come from a variety of industry and professional backgrounds, and they are exposed to diverse operational methods and strategies during class activities or assignments. Furthermore, becoming personally acquainted with project team members opens opportunities for building connections that might be professionally beneficial in the future.

Institutions of higher learning have become fundamentally self-contained communities. Each one functions almost like a small city, with students mingling throughout the day with people at all stages of life, from multiple backgrounds, and in various roles. It is a great place to start building a foundation of personal contacts or enhancing your current portfolio of contacts before entering a competitive world.

Exercise: What I Need and Who I Know

Create a table with two columns. On the left, list questions or issues associated with starting a new business, such as: How much money do I need to start? What licenses should I get? Do I lease or buy? Where do I find customers? Where do I find employees? How does payroll work? What kind of insurance should I get?

On the right side, write down specific answers that you already know. For questions and issues that you can’t answer, write down the name of a person you could ask to help answer that issue. If you do not know someone, who might help you get to the person who can give you an answer?

Local Organizations

Every community includes groups of individuals who have something in common. People group themselves together around shared beliefs, objectives, responsibilities, goals, or situations. Joining a local organization can place thousands of potential connections within your reach. Before seeking acceptance into a specific group, consider the type of group that fits your own personal and professional goals, and what you can contribute to the group’s continuity.

An open group has a fluid membership; people may freely join or separate at any given time. Open groups tend to be informal, operate around a loose structure, and frequently focus on a personal or social cause. Open-membership groups include activities-oriented groups such as bridge clubs, scrapbooking groups, or photography clubs. Some open groups, such as Mothers Against Drunk Drivers (MADD) or People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), focus on a specific topic or cause.

A closed group typically has either formal or informal criteria that you must meet before you can become a full member. Some organizations require sponsorship by a current member. Examples of closed groups include religious organizations, homeowners’ or renters’ associations, community performing arts groups, or sports groups.

Some community groups have features common to both open and closed groups. These hybrid groups have barriers or criteria that you must meet prior to joining, but those barriers are low, and prospective members can easily meet the criteria. Frequently, low barriers are an administrative feature to distinguish between participants who are serious about the group’s activities and those who have an impulsive interest with no long-term commitment to the cause. Table 6.1 shows the differences among open, closed, and hybrid groups.

Table 6.1: Open, Closed, and Hybrid Groups

| Open Groups | Closed Groups | Hybrid Groups |

| • Fluid membership

• Loosely structured, informal • May focus on personal/social cause |

• Membership criteria/process

• Structured • Formal purpose |

• Low barriers to membership

• Maintain barriers to ensure members are serious |

Groups that have a formal legal structure, an oversight board, and a professional management staff are typically more effective than those groups that are impulsively formed around a good idea. Professionally organized groups have skilled employees who set long-term goals and handle day-to-day activities. With the increase in structure and management, costs increase. To cover employee wages and benefits along with operational expenses of the group, many professional groups have membership dues and revenue-generating activities that members are expected to participate in. Some professional groups are self-supporting, whereas others are joint efforts among local and regional governments, universities, and the private sector.

One of the most successful private-public partnerships is the chamber of commerce arrangement. Local business entities establish a chamber of commerce organization to enhance the local community while expanding their own businesses. In some instances, the local government provides some type of monetary support for the chamber, but the chamber is neither an agency nor a function of government. For major community events, business members of a local chamber of commerce may provide their employees as volunteer staff who use their professional skills to organize and plan the event’s activities. The community benefits, because a professionally managed event is held with minimal labor costs. The company receives publicity and exposure to potential customers within the local community at nominal costs. A close working partnership between the local chamber of commerce and government can produce outcomes that are mutually beneficial to local businesses and community citizens.

Trade associations are formed within specific industries and concentrate their efforts on issues and topics particular to one trade, profession, or philosophy. Functional trade associations include auto mechanics (Automotive Maintenance Repair Association, amra.org), architects (the Association of Licensed Architects, www.alatoday.org/), and marketing professionals (American Association of Advertising Agencies, www.aaaa.org). Education groups, such as the Association of American Educators, focus on defining competencies and qualifications for teachers and publicly advocating for standards and regulations that affect teachers. Specialized groups also form associations, such as the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Entrepreneurs who are looking for a franchise opportunity might consider an association that caters to franchisees, such as the International Franchise Association (www.franchise.org) or the American Association of Franchisees and Dealers (www.aafd.org). Companies interested in “going green” can join the Green Business Network at Green America (www.greenbusinessnetwork.org). AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons, aarp.org) targets retired individuals. Whatever the profession or industry, a trade association is certain to emerge to provide standards, training, support, and services to industry professionals and to be the industry’s collective voice to legislatures and government officials in establishing regulations, laws, and licensure qualifications.

Businesses need a steady supply of new customers to replace former customers who no longer have an active relationship with them. One of the main purposes of networking groups is to help entrepreneurs gain new customers. These groups come in all kinds and sizes. Business Network International (BNI, www.bni.com) is dedicated to providing qualified referrals to members. BNI limits its membership to only one person per industry or profession. Members are expected to exchange contact information regarding qualified potential customers.

Meetup (www.meetup.com) is a platform where people can meet others with similar interests in an electronic or face-to-face engagement. Meetup’s groups are social or professional, business or entertainment, or relational or transactional. Anyone can start a Meetup group if one doesn’t already exist for their needs or interests. Each group’s founders or members make the rules.

Whether a new entrepreneur needs a lot of support and guidance during the early stages of firm development, or a mature organization needs new potential customers, local organizations can provide an avenue to close connections and professionals who are committed to the local community and its businesses and people. As with all decisions, you must assess each opportunity in terms of the cost of membership and involvement in relation to the benefits you will receive over time.

Business Incubators

Business incubators are normally associations established by a consortium of local organizations such as a chamber of commerce, local banks and other traditional businesses, and universities to provide complementary support to startup businesses and those in the early stages of development. Services provided may include office space for rent at nominal charges; simple business expertise in accounting, legal matters, and marketing; and management support. Some incubators function as independent organizations, each with its own board of directors, whereas others may be stand-alone units of a university program. One of the best byproducts of being associated with business incubators is the communal contact with all the members’ connections. Business accelerators function much like business incubators, but often make some type of equity investment in their members’ companies. Because the financial commitment raises the stakes for accelerators, these organizations typically carefully screen their prospects and select only those businesses that have a reasonable chance of financial success. An entrepreneur who joins an accelerator can expect to receive a lot of support. Table 6.2 illustrates the differences between business incubators and accelerators.

Table 6.2: Characteristics of Business Incubators vs. Accelerators

| Functional Item | Incubators | Accelerators |

| Duration | One to five years | Three to six months |

| Cohorts | No | Yes |

| Business model | Rent; nonprofit | Investment; can also be nonprofit |

| Selection | Noncompetitive | Competitive, cyclical |

| Venture stage | Early or late | Early |

| Education | Ad hoc, human resources, legal | Seminars |

| Mentorship | Minimal, tactical | Intense, by self and others |

| Venture locations | On site | On site |

Service Corps of Retired Executives (SCORE)

The Service Corps of Retired Executives (SCORE) is a nonprofit organization based in Herndon, Virginia. SCORE partners with the federal Small Business Administration (SBA) and with retired executives from private businesses to offer education, training, and mentoring to small business owners. According to the SCORE website, it is the largest network of volunteer and expert business mentors, with around 350 chapters. Small business owners can attend a workshop or view training videos available on the website. Templates of financial statements and business and marketing plans are also available on the website. Perhaps the most valuable service SCORE offers is a one-to-one mentoring program that connects a business owner to a mentor with the specific skills that they need.

Additional Resources

The SCORE website includes a wealth of online resources on starting a business such as online courses and regional workshops. You can also fill out a form to request a mentor to help you start your entrepreneurial journey.

Government Agencies

Economic stability over the long term depends on a continual supply of new companies and organizations. A business entity will close when the owner decides to cease operations or achieves the goals of starting the business. Sometimes a business is unable to sustain operations or is forced into closure by regulatory agencies or licensing requirements. Regardless of why businesses close, new businesses must continually arise to replace them and grow the economy. Governments at the federal, state, county, and municipal levels have established agencies and programs to encourage new business development, support new businesses in the early years of operations, and help young businesses mature to the point of self-sustainment. These include the Small Business Association (SBA), Small Business Development Centers (SBDC), Women’s Business Centers, and HUBZones. Figure 6.2 illustrates some of the government agencies that assist small businesses.

Figure 6.2: Government agencies to support entrepreneurs and small business owners

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license

Small Business Administration

One of the most popular agencies that helps businesses in the startup and early operations stages is the SBA. The SBA was established as an agency of the US federal government in 1953. In 2012, the SBA merged with the divisions of the Department of Commerce, the Office of the US Trade Representative, the Export-Import Bank, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and the US Trade and Development Agency. At that time, the leadership of the SBA became a cabinet-level position.

The purpose of the SBA at the macro level is to assist and safeguard small businesses, protect and defend a competitive environment, and fortify the national economy. At the micro level, the SBA helps individuals “start, build, and grow” their businesses and companies through direct counseling, educational seminars and webinars, and public-private partnerships with institutions of higher education and foundations with similar goals and objectives. Some of the most important activities of the SBA revolve around finances for small businesses. The SBA provides education in finance and money management, and guarantees loans through private lenders for capital, inventory, and startup costs. A business must meet the SBA’s qualifications for funding, but the application and approval of the loan is handled at the local level by officers of a local bank or other SBA-approved financial vendor.

Once a business is established and operating, ongoing activities are necessary to generate the cash flow to sustain the business. The SBA supports the ongoing operations of small businesses by being the liaison between small businesses and the federal government on bids and contracts. For fiscal year 2017, the federal government purchased a total of $105 billion[5] in products from small businesses.[6] However, becoming a vendor to the US government is not like selling to a private business or the general public. Free education and training materials are available from the SBA to introduce new businesses to the types of products that the government buys, the government’s purchasing process for products and services, and the technical terms the government uses.

The SBA helps small businesses to maneuver through government purchasing processes through education, training, and support. Furthermore, the SBA has programs and funding operations that help economically disadvantaged individuals. These programs are self-contained within the SBA. Public-private partnerships or partnerships with universities or with other nonprofit organizations are also possible.

Small Business Development Centers (SBDCs)

Over one thousand SBDCs are funded through state grants with matching funds from the SBA.[7] Most SBDCs are located on the campuses of local colleges or universities. Others are located in entrepreneurial hubs or are connected with business incubator programs.[8] The coordinator of a local SBDC may be an employee of either the university or the organization that provides the office space. SBDC coordinators provide advice and information to small business owners at no charge because their fees and salaries are covered by the grants. Mostly, the coordinators provide information, steer business owners to other sources of information, and provide a context for making operational or strategic decisions.

Office of Women’s Business Ownership

The Women’s Business Center (WBC) is a program funded in part or in whole by the SBA to focus specifically on helping women start and operate their own businesses.[9] Women business owners face the same challenges that men encounter, but women normally must add the role of business owner to their list of other personal responsibilities. Also, women have more limitations in access to capital and other financial resources than men typically experience. The WBC can provide support and access to resources that are unique to women. The WBC is operated through independent and educational centers in most states.

Veteran’s Business Outreach Center (VBOC)

The SBA operates twenty VBOCs that focus on helping veterans and their families start and operate a new business.[10] A popular program of the VBOC is the Boots to Business program, which assists veterans making the transition from the military to the owner-operator role. Another program dedicated to veterans is the Service-Disabled Veteran-Owned (SDVO) Small Business Concern (SBC) program, administered through the Office of Small and Disadvantaged Business Utilization. To qualify for the SDVO SBC program, the disabled veteran must directly own and control, at minimum, 51 percent of the business and have input into the day-to-day operations as well as a long-term strategy. Requirements vary according to the legal structure that is chosen.[11]

HUBZone

A HUBZone is a geographic location that has historically experienced low employment.[12] Many are also low-income areas because of limited transportation or educational opportunities. Through the HUBZone program, the SBA certifies and supports HUBZone businesses in acquiring government contracts and buying opportunities. Businesses that qualify may receive preferences in pricing. Qualifications for HUBZone designation are explained on the SBA/Government Contracting webpage. As of 2018, the federal government’s goal is to award 3 percent of all federal contracting dollars to certified HUBZone business.

Building the Entrepreneurial Dream Team

Over the weekend of July 4, 1970, Casey Kasem started American Top 40, a radio broadcast that played songs listed in Billboard magazine’s top 100 singles. What started as a simple compilation of popular songs that were played in ascending order of popularity ended thirty-nine years later on the July 4th weekend of 2009. When Kasem signed off for the final time, he gave credit to those with whom he worked. “Success doesn’t happen in a vacuum. You’re only as good as the people you work with and the people you work for. I’ve been lucky. I’ve worked for and with the very best.”[13]

Entrepreneurial success is sustained by those around you. The concept that teamwork leads to individual success is evident in many other areas. All the great National Football League quarterbacks will tell you that they depend as much on their linemen as on their receivers. Pitchers in Major League Baseball need a very close relationship with their catchers, but the fielders are the ones who make most of the outs in the game and can make a pitcher look very good. Surgeons need nurses and anesthesiologists, police officers need good partners as well as dispatchers, ground troops need air support, and airline pilots need fantastic ground crews and maintenance crews, and so on.

In reality, no one works alone. As an entrepreneur, you have the luxury of searching, soliciting, and selecting your own team. Entrepreneurial success depends on who is included on that team, and who is excluded from the team.

Building a Cross-Disciplinary Team

Rarely does an entrepreneurial venture start or function due to the effort of only one person. “Birds of a feather flock together” may be a popular saying, but it is a very poor organizational strategy for building a team to start a successful business. Diversity is a key feature of successfully managed organizations. Compatibility and collaboration are also important, as each employee is duty-bound to work with, support, and assist other employees when necessary. Having staff with complementary skills and who get along improves the likelihood of success for a new business.

A new restaurant provides a great example of how employees with assorted talents, expertise, and responsibilities are assembled to make a bustling organization profitable. For a new owner, the first hire is a manager. Hiring a good manager with experience means a larger payroll expense but produces better financial dividends over the long term. A good manager oversees all staff as well as all operational functions such as scheduling, buying, pricing, marketing, health code compliance, and business support functions. Perhaps the second key hire is the chef, who is responsible for creating the menu, distinguishing the restaurant from its competitors, and creating repeat customers who want high-quality, tasteful meals.

Front-house employees—the hosts/hostesses, servers, and bussers—play critical roles as the faces and voices of a restaurant. The first experience in a restaurant will leave a lasting impression, so those at the front are obliged to appear and act professional at all times. Servers, who have the most direct contact with customers, are the sales force of the business and the liaison with the chef. Servers’ incomes depend on tips and turning tables, so it is essential for them to have tables cleared quickly and properly prepared for the next group. Servers, therefore, rely heavily on the bussers for those important tasks. In many restaurants, bussers receive a portion of the tips left for the servers, establishing a codependency between those two key positions.

Other positions in a restaurant are the bartender, dishwasher, custodian, payroll clerk, bookkeeper, and so on who must perform their duties accurately and efficiently. Subpar service in any one of these functions jeopardizes the viability of the restaurant. Every employee at each and every level is crucial, individually as well as collectively.

Exercise: Make a List, Check It Twice

Building a team is a skill that you can learn. One of the first steps is to identify what tasks need to be completed and what skills are necessary to complete those tasks. People in all types of leadership positions build teams. Whether they are in government, large businesses, individual retail stores, small businesses, local athletic teams, or schools, leaders go through the same process of identifying tasks and the skills necessary to accomplish those tasks and then searching for people with those skills.

A key to learning is practice. You can practice building a team and then checking with people in charge of various organizations on how well you did. For example, select a local organization that you are somewhat familiar with—a local school, a community athletic league, a church, or a scout group. List the tasks and skills you think are needed to run the organization successfully. Then observe the organization in action. Make adjustments to your list. Ask to consult the manager in charge to see how well you did. How does your list compare with the actual operational structure? How is your list different? What did you overlook? How many people are doing more than one task?

After doing this a few times, you will begin to see organizations from a functional viewpoint. This is a skill any entrepreneur needs to have. What does my business do? What skills are needed to do those activities? Which person will I select to do those activities? If my first choice declines, who will be the backup?

Not only does a business need people to perform functional activities and day-to-day operations, but it also needs people to advise in other areas such as strategy, finances, management, staff, or legal. Should I have sales? Special promotions? Expand my product lines? Raise my prices? Get another investor for expansion? What are your long-term objectives? How will you achieve them? Having individuals you can talk to about your long-term goals is important. Surrounding yourself with those who can ask the right questions, confront you on weak areas, make you consider topics that you had not considered—all without judging you—is important if you have any plans to grow your business.

Create a second list of people you know and trust, a list solely for advising purposes. Members on this list can be from any industry as these are strategic questions, relevant across all industries and markets. They will help with your business strategy and structure, not operations.

A very common organizational structure for a new venture is the flat organization, consisting of family members, friends, or professional colleagues who take responsibility for different tasks. The bond that brings this group together in launching this new business is unlikely to bring to the table all of the skills, talents, personalities, perspectives, and viewpoints that can lead to long-term success. Therefore, expanding the team’s human resources beyond the founding members who also manage the business is crucial. Although they do not have to become employees, access to them is as vital as having key personnel on your payroll.

An entrepreneur with a creative or big-picture mindset may not want to be bothered by day-to-day activities. If that is the case, then someone else in the business needs to be the analytical, linear-thinking individual who can process information and data to make sound decisions. After carefully considering a situation, collecting information, and studying all relevant facts affecting the business, a problem solver can recommend what action the entrepreneur should take, to whom should the tasks be assigned, when to implement the solution, and how much money to dedicate to solving the problem. In other words, the problem solver becomes a lead advisor to the entrepreneur, the manager. If the creative entrepreneur is one side of the coin, the problem solver is the other side. When those two minds work in tandem, good things can happen.

In contrast, an entrepreneur may be a functional expert or licensed professional who is obliged to perform the tasks personally—for example, an HVAC technician, dentist, or professional driver. In that case, a business manager is needed to run the business side of the company. Rules, regulations, and deadlines for business activities are beyond the functional entrepreneur’s scope of interest, but they must be complied with accurately and in a timely manner, or the business may close. Like the creative founder who hires a day-to-day manager, a performance entrepreneur needs to hire someone dedicated to business functions.

Successful business owners keep careful track of metrics. They categorize and track expenses and analyze profit margins, production performance improvements or declines, employee attendance, and other measurable activities. Accurately interpreting the financial and operational performance of the company by the numbers provides the management team the information they need to make sound decisions. Having someone on the team with an aptitude for working with numbers is critical. The numbers must speak for themselves. Personnel must remain inside the box when they draw conclusions from data.

However, solutions to problems are not always inside the box. Nonlinear thinking, also known as creativity, or “thinking outside of the box,” is sometimes needed to solve problems. Creativity is the source of many new ideas, products, and processes. With companies facing shorter times of competitive advantage, the entrepreneur needs to be constantly reinventing both self and company.

Over time, as the business grows, the entrepreneur makes the transition from owner-operator of a startup through the small- business phase to being the owner-operator of a mature business. Entrepreneurs eventually need to make the cognitive shift from working in a state of ambiguity to performing methodically in a predictable environment. A business model where routine, repetitiveness, and predictability occur is more appropriate for established businesses because it brings stability and confidence to employees, customers, lenders, and investors alike. Using time-tested business methods and learning from previous experiences, an entrepreneur may avoid pitfalls that could doom a startup company in the early stages.

Every organization—whether a for-profit, not-for-profit, political, religious, or social organization—relies on revenue. Recruiting the person who will generate income for the organization should be a high priority during the earliest stages, perhaps even before formal operations, of the business. For a salesperson, grant writer, donor coordinator, or any other title referring to an income-generating position, a startup organization may have to offer a sweeter-than-normal compensation package. If the person can produce revenue and generate cash flow in excess of their total cost of employment, then he or she is worth the costs of higher commissions and bigger bonuses.

Managing Team Development and Dynamics[14]

If you have been a part of a team—as most of us have—then you intuitively have felt that there are different “stages” of team development. Teams and team members often start from a position of friendliness and excitement about a project or endeavor, but the mood can sour and the team dynamics can go south very quickly once the real work begins.

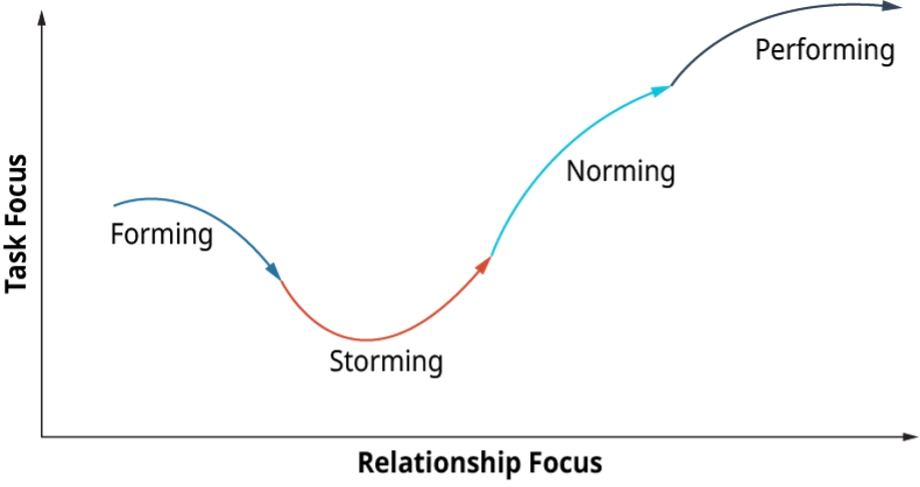

An educational psychologist named Bruce Tuckman (1965) developed a four-stage model to explain the complexities that he had witnessed in team development. The original model was called Tuckman’s Stages of Group Development, and he added the fifth stage of “Adjourning” in 1977 to explain the disbanding of a team at the end of a project.

The ‘original’ four stages of the Tuckman model, shown below in Figure 6.3, are:

- Forming

- Storming

- Norming

- Performing

Figure 6.3: Tuckman’s Model of Team Development

Attribution: Rice University, OpenStax, licensed under CC-BY 4.0.

Attribution: Rice University, OpenStax, licensed under CC-BY 4.0.

- The Forming Stage

The Forming stage begins with the introduction of team members. This is known as the “polite stage” in which the team is mainly focused on similarities and the group looks to the leader for structure and direction. The team members at this point are enthusiastic, and issues are still being discussed on a global, ambiguous level. This is when the informal pecking order begins to develop, but the team is still friendly.

- The Storming Stage

The Storming stage begins as team members begin vying for leadership and testing the group processes. This is known as the “win-lose” stage, as members clash for control of the group and people begin to choose sides. The attitude toward the team and the project begin to shift negative, and there is frustration around goals, tasks, and progress. The Storming Stage In the storming stage, protracted competition vying for the leadership of the group can hinder progress. You are likely to encounter this in your coursework when a group assignment requires forming a team.

- The Norming Stage

After what can be a very long and painful Storming process for the team, slowly the Norming stage may start to take root. During Norming, the team is starting to work well together, and buy-in to group goals occurs. The team is establishing and maintaining ground rules and boundaries, and there is a willingness to share responsibility and control. At this point in the team formation, members begin to value and respect each other and their contributions.

- The Performing Stage

Finally, as the team builds momentum and starts to get results, it is entering the Performing stage. The team is completely self-directed and requires little management direction. The team has confidence, pride, and enthusiasm, and there is a congruence of vision, team, and self. As the team continues to perform, it may even succeed in becoming a high-performing team. High-performing teams have optimized both task and people relationships—they are maximizing performance and team effectiveness.

The four stages of team development in the Tuckman model are not linear, and there are also factors that may cause the team to regress to an earlier stage of development. When a team member is added to the group, this may change the dynamic enough and be disruptive enough to cause a backward slide to an earlier stage. Similarly, if a new project task is introduced that causes confusion or anxiety for the group, then this may also cause a backward slide to an earlier stage of development. Think of your own experiences with project teams and the backslide that the group may have taken when another team member was introduced. You may have personally found the same to be true when a leader or project sponsor changes the scope or adds a new project task. The team has to re-group and will likely re-Storm and re-Form before getting back to Performing as a team.

Starting the Startup Team[15]

Nothing is more exciting than a startup business. The enthusiasm is high, and people are excited about the new venture and the prospects that await. Depending on the situation, there may be funding that the startup has received from investors, or the startup could be growing and powering itself organically. Either way, the startup faces many different questions in the beginning, which will have a tremendous impact on its growth potential and performance down the road. One of the most critical questions that face a startup —or any business for that matter—is the question of who should be on the team. Human capital is the greatest asset that any company can have, and it is an especially critical decision in a startup environment when you have limited resources and those resources will be responsible for building the company from the ground up.

In Noam Wasserman’s article (2012) “Assembling the Startup Team”, Wasserman asserts:

“Nothing can bedevil a high-potential startup more than its people problems. In research on startup performance, venture capitalists attributed 65% of portfolio company failures to problems within the startup’s management team. Another study asked investors to identify problems that might occur at their portfolio companies; 61% of the problems involved team issues. These problems typically result from choices that founders make as they add team members…”

These statistics are based on people problems in startups, and it isn’t quite clear what percent of larger company failures could be directly or indirectly attributed to people and team issues. I would imagine that the percentage is also significant. The impact of people problems and team issues in a startup organization that is just getting its footing and trying to make the right connections and decisions can be very significant. If you know anyone who has a company in startup mode, you may have noticed that some of the early team members who are selected to join the team are trusted family members, friends, or former colleagues. Once a startup company grows to a certain level, then it may acquire an experienced CEO to take the helm. In any case, the startup is faced early on with important questions on how to build the team in a way that will maximize the chance of success.

In “Assembling the Startup Team,” Wasserman refers to the three Rs: relationships, roles, and rewards as being key elements that must be managed effectively in order to avoid problems in the long term. Relationships refer to the actual team members that are chosen, and there are several caveats to keep in mind. Hiring relatives or close friends because they are trusted may seem like the right idea in the beginning, but the long-term hazards (per current research) outweigh the benefits. Family and friends may think too similarly, and the team misses the benefit of other perspectives and connections. Roles are important because you have to think about the division of labor and skills, as well as who is in the right roles for decision-making. The startup team needs to think through the implications of assigning people to specific roles, as that may dictate their decision power and status. Finally, defining the rewards can be difficult for the startup team because it essentially means that they are splitting the pie—i.e., both short-term and long-term compensation. For startup founders, this can be a very difficult decision when they have to weigh the balance of giving something away versus gaining human capital that may ultimately help the business to succeed. Thinking through the tradeoffs and keeping alignment between the “three Rs” is important because it challenges the startup team to think of the long-term consequences of some of their early decisions. It is easy to bring family and friends into the startup equation due to trust factors, but a careful analysis of the “three Rs” will help a startup leadership team make decisions that will pay off in the long term.

Chapter 6 References

[1] Chapter 6: Building a Network” is derivative of Entrepreneurship by Michael Laverty & Chris Littel, CC licensed by OpenStax, Chapter 12 (Building Networks).

[2] Alice Hopkins. “The Development of the Overseas Highway.” Tequesta: The Journal of the Historical Association of Southern Florida 46 (1986): 48–58. http://digitalcollections.fiu.edu/tequesta/files/1986/86_1.pdf

[3] Chris Mooney. “The Race to Save Florida’s Devastated Coral Reef from Global Warming.” Washington Post. June 25, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/classic-apps/the-race-to-save-floridas-devastated-coral-reefs-from-global-warming/2017/06/25/a1bd899a-3fa9-11e7-adba-394ee67a7582_story.html

[4] This section is derivative of Principles of Leadership & Management (2022) by Laura Radtke, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licensed (Chapter 10.10 Personal, Operational, and Strategic Networks).

[5] Small Business Administration. www.sba.gov

[6] Robb Wong. “New SBA FY17 Scorecard Shows Federal Agencies Award Record Breaking $105 Billion in Small Business Contracts.” US Small Business Administration. May 22, 2018. https://www.sba.gov/blogs/new-sba-fy17-scorecard-shows-federal-agencies-award-record-breaking-105-billion-small-business

[7] America’s SBDC (Small Business Development Centers). n.d. https://americassbdc.org

[8] US Small Business Administration. “Find Local Assistance.” n.d. https://www.sba.gov/sbdc

[9] US Small Business Administration. “Office of Women’s Business Ownership.” n.d. https://www.sba.gov/offices/headquarters/wbo

[10] US Small Business Administration. “Office of Veteran’s Business Development.” n.d. https://www.sba.gov/offices/headquarters/ovbd

[11] Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. n.d. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/ECFR?page=browse

[12] US Small Business Administration. “Office of the HUBZone Program.” n.d. https://www.sba.gov/offices/headquarters/ohp

[13] Cord Himmelstein. “Casey Kasem’s Final Sign-Off.” Halo Recognition. June 19, 2014. http://www.halorecognition.com/casey-kasems-final-sign-off

[14] This section is derivative of Principles of Leadership & Management (2022) by Laura Radtke, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licensed (Chapter 10.3 Team Development Over Time).

[15] This section is derivative of Principles of Leadership & Management (2022) by Laura Radtke, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licensed (Chapter 10.3 Team Development Over Time).