5 Chapter 5: Generating Innovative Solutions

Understanding Creativity

Creative thought is a mental process involving creative problem solving and the discovery of new ideas or concepts, or new associations of the existing ideas or concepts, fueled by the process of either conscious or unconscious insight. From a scientific point of view, the products of creative thought (sometimes referred to as divergent thought) are usually considered to have both originality and appropriateness.

Although intuitively a simple phenomenon, it is in fact quite complex. It has been studied from the perspectives of behavioral psychology, social psychology, psychometrics, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, philosophy, aesthetics, history, economics, design research, business, management, and communication, among others. The studies have covered everyday creativity, exceptional creativity, and even artificial creativity. Unlike many phenomena in science, there is no single, authoritative perspective or definition of creativity. And unlike many phenomena in psychology, there is no standardized measurement technique.

Creative problem solving is the process of creating a solution to a problem. It is a special form of problem-solving in which the solution is independently created rather than learned with assistance. Creative problem solving always involves creativity. However, creativity often does not involve creative problem solving, especially in fields such as music, poetry, and art. Creativity requires newness or novelty as a characteristic of what is created, but creativity does not necessarily imply that what is created has value or is appreciated by other people. To qualify as creative problem solving the solution must either have value, clearly solve the stated problem, or be appreciated by someone for whom the situation improves (Fobes, 1993).

Distinguishing Between Creativity and Innovation

It is often useful to explicitly distinguish between creativity and innovation. Creativity is typically used to refer to the act of producing new ideas, approaches, or actions, while innovation is the process of both generating and applying such creative ideas in some specific context.

In the context of an organization, therefore, the term innovation is often used to refer to the entire process by which an organization generates creative new ideas and converts them into novel, useful, and viable commercial products, services, and business practices, while the term creativity is reserved to apply specifically to the generation of novel ideas by individuals or groups, as a necessary step within the innovation process. For example, Amabile et al. (1996) suggest that while innovation “begins with creative ideas,”

“…creativity by individuals and teams is a starting point for innovation; the first is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the second.”

Although the two words are distinct, they go hand in hand. To be innovative, you have to be creative.

Engaging in Ideation

Entrepreneurial creativity and artistic creativity are not so different. You can find inspiration in your favorite books, songs, and paintings, and you also can take inspiration from existing products and services. You can find creative inspiration in nature, in conversations with other creative minds, and through formal ideation exercises, for example, brainstorming. Ideation is the purposeful process of opening up your mind to new trains of thought that branch out in all directions from a stated purpose or problem. Ideation aims to generate lots of ideas. Brainstorming, the generation of ideas in an environment free of judgment or dissension with the goal of creating solutions, is just one of dozens of methods for coming up with new ideas.

When you plan to engage in ideation, you can benefit from setting aside a sizeable chunk of time. Reserving time to let your mind roam freely as you think about an issue or problem from multiple directions is a necessary component of the process. Ideation takes time and a deliberate effort to move beyond your habitual thought patterns. If you consciously set aside time for creativity, you will broaden your mental horizons and allow yourself to change and grow.

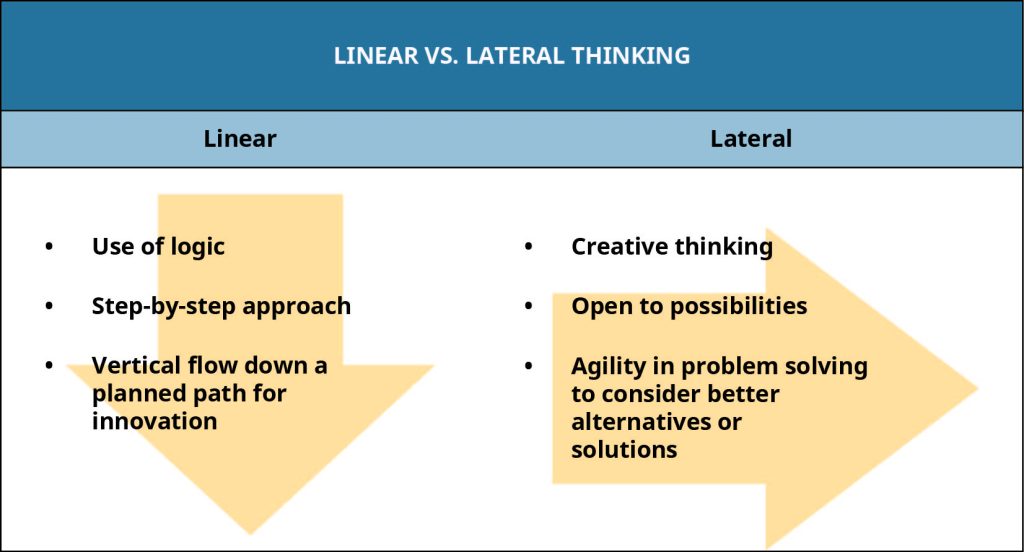

In order to better understand how ideation fits in the process of entrepreneurship and problem solving, it’s important to acknowledge different ways of thinking. First, we can compare linear and lateral thinking. Linear thinking—sometimes called vertical thinking—involves a logical, step-by-step process. In contrast, creative thinking is more often lateral thinking, free and open thinking in which established patterns of logical thought are purposefully ignored or even challenged. When you ignore logic, anything becomes possible. Linear thinking is crucial in turning your idea into a business, but lateral thinking will allow you to use your creativity to solve problems. Figure 5.1 below summarizes linear and lateral thinking.

Figure 5.1 Linear vs. Lateral Thinking

We should also consider the different between divergent and convergent thinking – both of these types of thinking are critical in the ideation process, as they work together to help you come up with fresh solutions.

Divergent thinking is represented in brainstorming efforts to generate many options and ideas as possible. Whether working in a group or as a team of one, divergent thinking is a valuable activity to move beyond obvious solutions. You should aim to create both fluency (i.e., volume) and flexibility (i.e., variety) of ideas (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2 Divergent Thinking for Volume and Variety

The ultimate goal of divergent thinking is to create new solutions for the problems you want to solve. The immediate goal is to multiply your insights and ideas. Insights become valuable when you can act on them as inspiring opportunities. To get there, turn your insights into questions, which can then serve as the springboard for your ideas. Brainstorming, one particular approach to divergent thinking, will be described further later in the chapter.

Once you have generated a substantial quantity of diverse ideas, you will need to rank, sort, combine, and select the best of those ideas for further development. This entails convergent thinking. Convergence is fundamentally about arriving at conclusions by making connections, or synthesizing data, ideas, and insights. Put differently, it’s about connecting the dots (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 Convergent Thinking to Connect the Dots

Tim Brown, co-founder of IDEO (a consulting firm that specializes in human-centered design), describes the importance of convergent thinking as follows: “Synthesis, the act of extracting meaningful patterns from masses of raw information, is a fundamentally creative act… The data are just that—data—and the facts never speak for themselves.”

Let’s now consider some of the creativity techniques that promote original thoughts by facilitating divergent and/or convergent thinking.

Creativity Techniques

Creativity techniques are a collection of tools and methods that support the creation of effectives solution to a problem. Creative-problem-solving techniques can be categorized as follows:

- Creativity techniques designed to shift a person’s mental state into one that fosters creativity. One such popular technique is to take a break and relax, go for a walk, or sleep after intensively trying to think of a solution.

- Creativity techniques designed to reframe the problem. For example, reconsidering one’s goals by asking “What am I really trying to accomplish?” can lead to useful insights.

- Creative problem-solving techniques designed to efficiently lead to a fresh perspective that causes a solution to become obvious. This category is useful for solving especially challenging problems (Fobes, 1993). Some of these techniques involve identifying independent dimensions that differentiate (or separate) closely associated concepts (Fobes, 1993). Such techniques can overcome the mind’s instinctive tendency to use “oversimplified associative thinking” in which two related concepts are so closely associated that their differences, and independence from one another, are overlooked (Fobes, 1993).

- Creativity techniques designed to increase the quantity of fresh ideas. This approach reflects the belief that a larger number of ideas increases the chances that one of them has value. Some of these techniques involve randomly selecting an idea (such as choosing a word from a list), thinking about similarities with the undesired situation, and hopefully inspiring a related idea that leads to a solution. Brainstorming is one such technique.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a commonly used creativity technique designed to generate a large number of ideas for the solution of a problem. In 1953 the method was popularized by Alex Faickney Osborn in a book called Applied Imagination. Osborn proposed that groups could double their creative output with brainstorming.

Brainstorming encourages you to think expansively and without constraints. It’s often the wild ideas that spark visionary thoughts. Brainstorming may often be thought of as wild and unstructured, but it in fact is a focused activity that involves a lot of discipline. With careful preparation and a clear set of rules, a brainstorm session can yield hundreds of fresh ideas.

Here are some tips to kickstart your brainstorming work:

- Start with a well-defined topic. Think about what you want to get out of the session and stay focused on your topic.

- Aim for quantity to reach quality. More ideas means more opportunities for a great solution to emerge. Set an outrageous goal for the number of ideas you want to generate—then surpass it. The best way to find one good idea is to come up with lots of ideas.

-

Choose brainstorm questions. Select three to five questions for your brainstorm session. Trust your gut feeling: choose those questions that feel exciting and help you think of ideas right away. Also, select the questions that are most important to address, even if they feel difficult to solve for.

-

Defer judgement. There are NO bad ideas at this point. There will be plenty of time to narrow them down later, during the convergence phase.

-

Generate unusual, even “wild” ideas. When brainstorming, analogous inspiration is your best friend. Bring in random influences to help spark new thinking. Even if some of your ideas seem silly or impossible, this is the time when you can use your imagination.

-

Be visual and “sketch to think”. Sketching even a simple representation of an idea makes you think through a lot of details. Stick figures, mind maps, and simple sketches can say more than many words. Brainstorm ways to bring your concept to life early to figure out how you might take an idea further. Draw your ideas, as opposed to just writing them down.

- Develop “how might we” questions. Evolve your ideas by asking “How might we…?” or “What if…?” questions about each of them. This will encourage you to imagine avenues for further exploration, and to come up with plans to work around constraints you might be facing.

Expand your ideas to further develop them by asking:

- Who can use this and what problem does it solve?

- Where and when will this be used?

- How can I improve this idea?

- What do I need to make this idea work?

Variations of Brainstorming

There are many variations of brainstorming that people in search of ideas may find useful, including (1) nominal group technique, (2) group passing technique, (3) team idea mapping method, (4) electronic brainstorming, (5) directed brainstorming, and (6) question brainstorming.

Nominal group technique

The nominal group technique is a type of brainstorming that encourages all participants to have an equal say in the process. It is also used to generate a ranked list of ideas.

Participants are asked to first write down their ideas. Then they each share their ideas orally or the moderator collects the ideas and each is voted on by the group. The vote can be as simple as a show of hands in favor of a given idea. This process is called distillation. After distillation, the top-ranked ideas may be sent back to the group or subgroups for further brainstorming. For example, one group may work on the color required in a product. Another group may work on the size, and so forth. Each group will come back to the whole group for ranking the listed ideas. Sometimes ideas that were previously dropped may be brought forward again once the group has re-evaluated the ideas. Like all team efforts, it may take a few practice sessions to train the team in the method before tackling the important ideas.

A variation of nominal technique called affinity technique involves using Post-it notes to first generate ideas and then work together to categorize the Post-it notes (see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Affinity Technique in Action

Group passing technique

In the group passing technique, each person in a circular group writes down one idea and then passes the piece of paper to the next person in a clockwise direction, who adds some thoughts. This continues until everybody gets his or her original piece of paper back. By this time, it is likely that the group will have extensively elaborated on each idea.

The group may also create an “Idea Book” and post a distribution list or routing slip to the front of the book. On the first page is a description of the problem. The first person to receive the book lists his or her ideas and then routes the book to the next person on the distribution list. The second person can log new ideas or add to the ideas of the previous person. This continues until the distribution list is exhausted. A follow-up “read out” meeting is then held to discuss the ideas logged in the book. This technique takes longer, but it allows individuals time to think deeply about the problem.

Idea mapping method

The idea mapping method of brainstorming works by the method of association. It may improve collaboration and increase the quantity of ideas, and is designed so that all attendees participate and no ideas are rejected.

The process begins with a well-defined topic. Each participant brainstorms individually, then all the ideas are merged onto one large idea map. During this consolidation phase, participants may discover a common understanding of the issues as they share the meanings behind their ideas. During this sharing, new ideas may arise by the association, and they are added to the map as well. Once all the ideas are captured, the group can prioritize and/or take action.

Electronic brainstorming

Electronic brainstorming is a version of the manual brainstorming technique that relies on digital tools like video conference calls, collaborative documents, chat tools, or even email. Participants share a list of ideas, which are entered independently. In synchronous electronic brainstorming, contributions become immediately visible to all and are typically anonymized to encourage openness and reduce personal prejudice. Some digital tools may allow for asynchronous brainstorming sessions over extended periods of time as well as typical follow-up activities in the creative problem-solving process such as categorization of ideas, elimination of duplicates, assessment, and discussion of prioritized or controversial ideas.

Electronic brainstorming eliminates many of the problems of standard brainstorming, such as production blocking and evaluation apprehension. An additional advantage of this method is that all ideas can be archived electronically in their original form, and then retrieved later for further thought and discussion. Electronic brainstorming also enables much larger groups to brainstorm on a topic than would normally be productive in a traditional brainstorming session (Gallupe et al., 1992).

Some web-based brainstorming techniques allow contributors to post their comments anonymously. This technique also allows users to log on over an extended time period, typically one or two weeks, to allow participants some “soak time” before posting their ideas and feedback.

Directed brainstorming

Directed brainstorming is a variation of electronic brainstorming. It can be done manually or with computers. Directed brainstorming works when the solution space (that is, the criteria for evaluating a good idea) is known before the session. If known, that criteria can be used to intentionally constrain the ideation process.

In directed brainstorming, each participant is given one sheet of paper (or electronic form) and told the brainstorming question. They are asked to produce one response and stop, then all of the papers (or forms) are randomly swapped among the participants. Similar to the group passing technique described above, participants are asked to look at the idea they received and to create a new idea that improves on that idea based on the initial criteria. The forms are then swapped again and respondents are asked to improve upon the ideas, and the process is repeated for three or more rounds. In the laboratory, directed brainstorming has been found to almost triple the productivity of groups over electronic brainstorming (Santanen et al., 2004).

Question Brainstorming

Question brainstorming process involves generating questions, rather than trying to come up with immediate answers and short-term solutions. This technique stimulates creativity and promotes everyone’s participation because no one has to come up with answers. The answers to the questions form the framework for constructing future action plans. Once the list of questions is set, it may be necessary to prioritize them to reach the best solution in an orderly way (Ludy, 2000). Another of the problems for brainstorming can be to find the best evaluation methods for a problem. Brainstorming all the questions has also been called questorming (Roland, 1985).

Evaluating Ideas

Once you have generated a substantial list of ideas through divergent thinking, it becomes necessary to focus in on the ideas that have the highest potential. This brings us to the phase of the ideation process that relies on convergent thinking. To practice convergent thinking, here are some steps to follow:

- Pattern quest. Cluster related ideas. Spend a few minutes immediately after a brainstorming session grouping together similar ideas into categories or buckets. Step back and identify important patterns that have emerged in your data. Try to find overlaps, themes, contradictions and tensions as they relate to each other.

- Grow an idea. Mix and match elements of ideas to create even better ones. By remixing and combining ideas, whether good or bad, feasible or infeasible, you will generate new ones.

- Narrow the set. When engaging in divergent thinking, you are developing ideas without giving much thought to the constraints you may face while attempting to realize it. With a shift to convergent thinking, it makes sense to now do a reality check: look at what’s most important about your idea and find ways to evolve and develop it further. Now is the time for evaluation. Decide what makes some of your ideas more feasible and viable than others. Look at all of the ideas you have generated, then decide which you want to try to build and test first.

- List constraints. Make a list of all the challenges and barriers you are facing with your idea. What are you missing? Who would oppose the idea? What will be most difficult to overcome? You can engage in additional brainstorming to consider how you might address some of these challenges.

- Archive ideas. Let go of ideas that feel too difficult to create, or that you are not excited about. But keep your Post-its and notes so you can revisit them later!

Here are some other idea evaluation techniques to help you explore ideas in more depth. In most cases it is useful to remember that your options aren’t necessarily limited to the ones that are currently on the table. If you can’t decide between two ideas, you can try to find a new option that combines the benefits of both, and addresses key concerns. These tools also help you to get a better understanding of your priorities, even if you don’t end up proceeding with any of the options exactly as they are.

Pros & Cons

This tool can be used to decide between different options and to identify different needs and priorities around an issue. For each idea, list the benefits (pros) and drawbacks (cons) and compare the results. Most groups will benefit from a third category of ‘other’ or ‘interesting’ to capture any points that aren’t obviously a pro or a con. You could do this in the form of a table or a mind map.

In groups, this process can be completed as a full group or in pairs. You could also task sub-groups to work on either the pros or the cons of a different idea each and then report back to the whole group. Sometimes groups find it helpful to score the pros and cons according to how significant of an advantage/disadvantage they are. For example, if a shared household was choosing a new kitchen table, ‘We can’t afford it’ might be ranked as 9/10, and ‘We don’t like the color’ might only rank 2/10, because it could be re-painted.

There are a few things to be aware of when considering pros and cons in a group. First, you may find that you don’t all agree on what is a pro and what is a con. Alternately, you might have different views on which pros and cons are most significant. This can be a great starting point for discussion about your differences. However, it helps to think in advance how you will take differences into account when taking note of people’s answers. For example, record the same point in both the pros and cons column if people don’t agree. Or, instead of trying to find a definitive whole-group score to measure how significant each point is, use a tool that allows each person to give their own answer.

Urgent/Important Grid

This is a classic time-management tool that can be applied to prioritizing ideas! First, map the ideas according to their urgency and importance. Urgency refers to the timeliness of an idea – things that are urgent must be addressed immediately. Importance, on the other hand, refers to how central an idea is to our key objectives. For example, as an entrepreneur, responding to an email from a supplier about a shipment may be urgent. In contrast, cultivating new customer relationships is a critically important task that doesn’t have a clear timeline, which can lead an entrepreneur to feel less urgency about it.

You can use this tool on a whiteboard, paper, or even the floor. If you are using the floor, it is best to mark the lines using string or masking tape, so that it is easy to see the whole grid. Add labels at the end of the lines to remind people what they mean (see Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5 Urgent/Important Grid

Ranking Ideas

This is a great technique for using in small groups. Write each idea on a card or post-it note, and give each group a full set of cards/notes. Set a time limit and ask the groups to rank the options, or to reduce the options to the top three options. It’s helpful to set out clear criteria for ranking at the start. For example, “You’ve got 15 minutes. We’re looking for ideas that need to be done most urgently, are most important, and yet realistic with the resources available. Also we’ve only got a month to make it happen, so please think about what we can realistically achieve in the time available.”

The Difference Between Ideas and Opportunities

Aspiring entrepreneurs can come up with ideas all day long. During the ideation phase, we stress that there are no such things as bad ideas in the spirit of being generative. But realistically, at the end of the day, not every idea is necessarily a good idea. In the field of entrepreneurship, specific criteria distinguish an idea from an opportunity. In other words, we must determine whether an idea meets the criteria by which is can be translated into an entrepreneurial opportunity. Entrepreneurial opportunity is the point at which identifiable consumer demand (i.e., is there a market) meets the entrepreneur’s ability to (profitably) deliver the requested product or service (i.e., do we have the resources and skills needed). This aligns with the three design thinking criteria that were previously highlighted: desirability, feasibility, and viability.

Once you have determined – through as many iterative rounds of divergent and convergent thinking as needed – that your idea has potential, you can begin to validate whether or not it represents an entrepreneurial opportunity. This requires additional market analysis, developing a business model, and testing and experimenting to refine your solution. These processes will be discussed further in future chapters.

Attributions: Material from the following open source texts was adapted and integrated into this chapter.

“Chapter 3: Ideate.” Sidneyeve Matrix. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://pressbooks.pub/innovationbydesign/chapter/ideate/

“Chapter 15: Enhancing Creativity in Groups.” J.R. Linabary. 2021. CC-BY-SA 4.0. https://pressbooks.pub/smallgroup/chapter/creativity/

“Chapter 4: Creativity, Innovation, and Inventon.” In Entrepreneurship. Michael Laverty & Chris Littel. CC-BY OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/entrepreneurship/pages/4-2-creativity-innovation-and-invention-how-they-differ

“Collective Action Toolkit” Frog Design. Circa 2016. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 https://www.frogdesign.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/CAT_2.0_English.pdf

“Design Thinking for Educators” IDEO. Circa 2013. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 https://designthinkingforeducators.com/toolkit/

“Design Thinking for 11th Graders” Bridget McGraw. Circa 2016. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 http://www.open.edu/openlearn/science-maths-technology/engineering-andtechnology/design-and-innovation/design/design-thinking/content-section-0

“Facilitation Tools for Meetings and Workshops.” Seeds of Change. 2020. CC-BY-NC-SA. https://www.seedsforchange.org.uk/downloads/tools.pdf

“The K12 Lab Network wiki” Circa 2015. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 https://dschool-old.stanford.edu/groups/k12/

This module describes the emotional roller coaster you ride when starting a company and suggests some principles for choosing your right approach. This emotional roller coaster represents a natural part of the entrepreneurship process, and you will find other chief executive officers (CEO), founders, and entrepreneurs go through similar experiences.

This module makes a case for being intrinsically motivated and passionate about problem solving as a method for surviving the emotional ups and downs of entrepreneurship.

The module covers the following topics:

- Romanticized CEO versus Reality CEO

- Recognizing The Hype Cycle

- Choosing Passion versus Profit and Risk versus Reward

- What Type of Entrepreneur Are You?

- What’s Your Motivation?

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Identify the ups and downs of being an entrepreneur

- Recall various concepts associated with entrepreneurship

- Discover personal motivations for considering entrepreneurship

Section A: Romanticized CEO versus Reality CEO

Modern media often romanticize startup founders as geniuses, visionaries, or mavericks. While becoming a chief executive officer (CEO), founder, or entrepreneur might offer the biggest buzz you’ve ever felt, entrepreneurship can also be a lonely activity. You may work harder than ever before, but may also spend long hours battling uncertainty. That’s why embarking on this journey requires conviction and passion to both embrace the joys of succeeding in your own business, and to survive both the naysayers and the emotional ups and downs.

To highlight both sides of this perspective, here are two examples:

| Romanticized CEO | Read about the glorification of the entrepreneur. |

| Reality CEO | Read about the realities of being a founder from the perspective of 2SLGBTQ+ entrepreneurs. |

Pause

Boyd Reid, Nick Baksh, and Tenille Spencer give their opinions on the reality of being an entrepreneur and discuss some specific challenges that they encountered on their entrepreneurial journey.

Reality CEO

The job description of a CEO is a bit of a paradox: it’s both simple and complex. A CEO has five main responsibilities:

1. Set & Communicate Strategy

The CEO sets the company’s strategy. Once that strategy gets established, the CEO needs to communicate their strategy clearly to everyone in the company.

Think of the startup as a ship and the CEO as the Captain. The ship and its crew want to sail from a starting point to a destination. The Captain charts the course and communicates the heading to the crew. If the crew misunderstands the direction, however, or worse decides to set their own course, the ship will lie stalled in the water. If it doesn’t sink first….

Authenticity and repetition should become key aspects of how CEO’s communicate to their teams. Great leaders communicate their strategy consistently and often. And if the strategy needs to change, a leader must have the confidence and authority to provide a rationale for this new direction. Ed Catmull former President of Pixar Studios summarized this concept well:

“As long as you have been candid and had good reasons for making your (now- flawed-in-retrospect) decisions, your crew will keep rowing. But if you find that the ship is just spinning around— and if you assert that such meaningless activity is, in fact, forward motion—then the crew will balk.

They know better than anyone when they are working hard but not going anywhere. People want their leaders to be confident. Andrew doesn’t advise being confident merely for confidence’ sake. He believes that leadership is about making your best guess and hurrying up about it so if it’s wrong, there’s

still time to change course.”Ed Catmull, Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration

In the article “Here's the Advice I Give All of Our First Time Founders”, First Round Capital partner, Rob Hayes, says:

“Your job is to get great people and get the best out of them. Even if this makes you uncomfortable, you'll find that really good things happen.”

“As a founder, part of your job is making the rounds and asking people, 'Hey, why are you doing that? How is that going to get us to our goal?' You want to start meaningful dialogues about this, not just so everyone keeps pulling together, but to make sure you're headed in the right direction.”

2. Set & Communicate Values

A company’s values inform its culture, meaning the written or unwritten rules that define how the company sells its products or services, hires its people and works with its customers. Those values are set from the beginning, and are best developed by considering some tradeoffs: Does your company value speed or accuracy? Does your company prioritize customer’s interests over shareholder’s interests?

Regardless of the values your organization lives by, the CEO must communicate these values clearly to their employees. That communication can come from the CEO’s words, but also from the ways they champion the organization's values in their day-to-day conduct; you may find that “lead by example” is both a cliché and a core CEO competency!

As with communicating your company’s strategy, demonstrating authenticity and using repetition can help to communicate your company’s values. For example, Jeff Bezos consistently communicates Amazon’s priority of putting customers’ interests first, above all else. From Bezos’ first shareholder letter in 1997 to today’s Amazon’s leadership principles, the phrase “Customer Obsession” comes up regularly.

3. Manage Finances

Startup research firm CB Insights, after conducting 101 startup post-mortems, highlights one of the reasons why startups fail: they run out of cash. Simply put, the CEO needs to keep cash in the bank account, and they can do this by:

- Leading sales efforts and closing sales

- Raising money from investors

- Managing cash flow and expenses

4. Build the Team

A startup may initially be the idea or passion of one person or a group of co-partners, but eventually entrepreneurs need to recruit people to join in actualizing their company’s vision. Every CEO wants to find, attract, and recruit early team members. Recruiting early team members, however, can create a difficult balancing act of:

- Recruiting people with the right skill sets at the right time needed to move the company forward

- Recruiting people who buy into the vision and align with the culture

- Convincing people to join a startup that is obviously risky, and which lacks the resources of a larger enterprise.

Here are a few quotes from Rob Hayes on early hires and building a team:

- “Growth is all about hiring the people who can give you momentum.”

- “If you hate hiring, hire all your top people right away and then let them do the rest.”

- “Find your lieutenants first.”

- “Start small with hiring — ideally with hires who can take something off [your] plate that [you] really shouldn't be doing.”

- “When you hire amazing people who are better than you at what they do, you look like a genius.”

- “Don't just hire the best; hire the best people for you.”

- “If you don't think you can convince amazing people to work for your company, you've got a much bigger problem.”

- “If you can't convince the people you want that your startup is the best possible opportunity, then you should find something else to do. A lot of founders get caught up in comparing the package they can provide, to compensation elsewhere. But this comes back to finding the right people for you.”

5. Everything else

In the world of startups, the CEO must set strategy, communicate authentically and consistently, manage cash flows, lead recruitment…and simply do whatever is required to ensure the business succeeds. In other words, you might start your day fine-tuning the CRM software, but end the day repairing the copy machine! In this article, “Black in Tech: Startup advice from Black founders who made it” Alexandra McCalla, co-founder of AirMatrix, provides some advice:

“You have to just get in and do the work every day. It’s not glamorous at all. I’ve done everything from filing receipts for the company, filing taxes, making decks, handling the logistics of shipping.”

How to Deal With Challenges

Launching and building a company can be extremely hard, but can also be a lot of fun. Enduring the ups and downs requires staying focused, both on solving problems and on creating value for customers in a way that rewards you financially and personally. Said another way, co-founder of Lifetise, Caroline Hughes shares:

“I’ve rejected the startup dogma that you have to move fast and break things, or always be “crushing it” or “killing it”. I’m doing none of those things. I’m building a thoughtful, empathetic FinTech business from the ground up. It’s slow going.”

Optional Reading

Hayes, Rob. “Here's the Advice I Give All of Our First Time Founders.”

Pinkett, Randal. “Black Faces in White Places”

Hughes, Caroline. “Why I'm Not Crushing It or Killing It in My Startup, and nor Should You.”

Finkelstein, Harley “Our Image of an Entrepreneur Desperately Needs an Update”

Agarwal, Pragya. It Is Time We Acknowledged Loneliness in Entrepreneurs and Did Something about It”.

Abrams, Stacey. “Lead from the Outside: How to Build Your Future and Make Real Change”.

Section B: Recognizing the Hype Cycle

The 1980s rap group, Public Enemy, said it best: “Don’t Believe the Hype.”

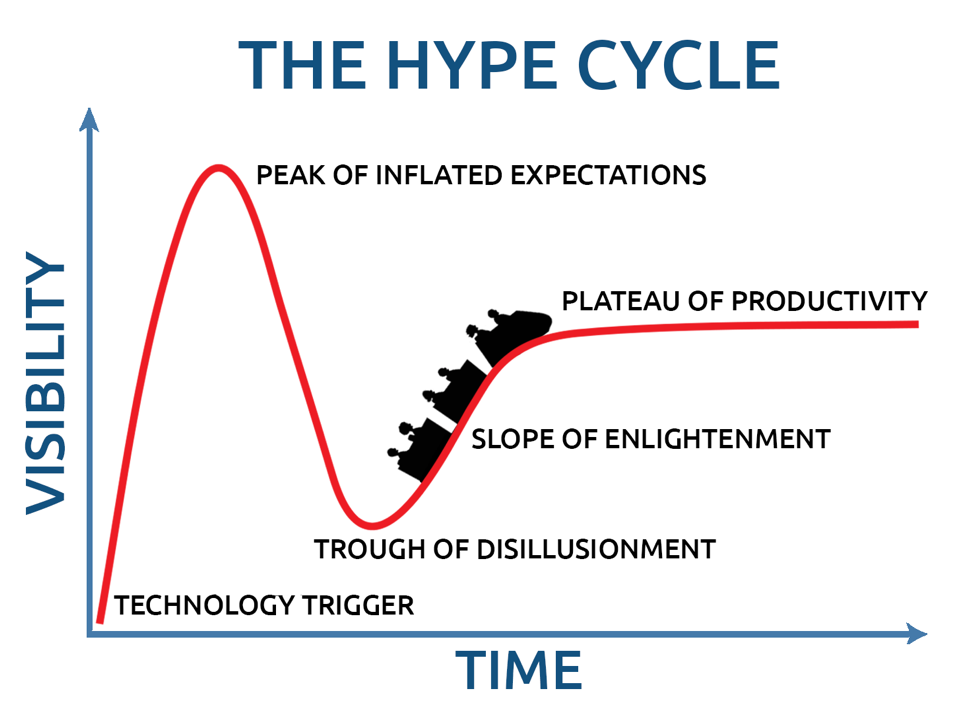

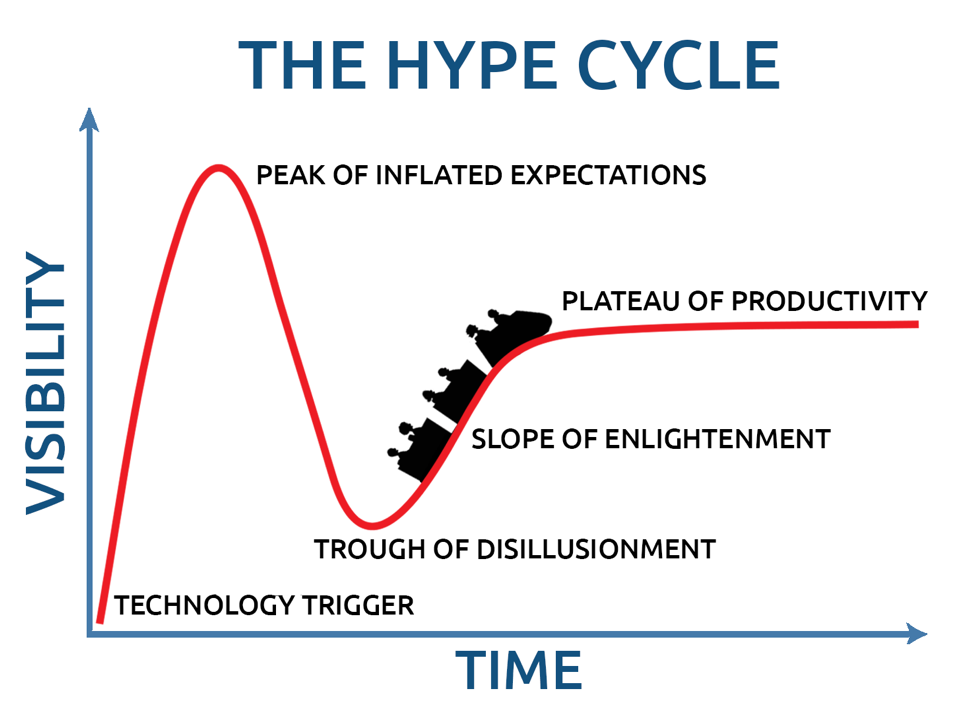

Gartner, a research consulting firm, developed the "Gartner Hype Cycle" to chart the development path of new technologies as they are invented and adopted. But the Hype Cycle can also chart the challenges many entrepreneurs experience when launching a new venture. The curve of the Hype Cycle resembles the curvature of a roller coaster drop and involves five phases.

Phase 1 - Innovation Trigger

This is the big bang moment when you have an idea. Everything seems possible and it all feels exciting.

Phase 2 - Peak of Inflated Expectations

You share your idea with friends and family who all support it. You get working on building it.

You pick a name, a logo, business cards, a website, and build a product or service. Your idea becomes a real thing as your excitement builds.

The article “The Struggle” pulls excerpts from Ben Horowitz’s management book “The Hard Things About Hard Things.” Ben Horowitz knows a little bit about how hard it is to build and run a company. Ben co-founded, built, IPO’d, saved from collapse, and sold Opsware for $1.65B. Now he is co-founder of Venture Capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

"Every entrepreneur starts her company with a clear vision for success. You will create an amazing environment and hire the smartest people to join you. Together you will build a beautiful product that delights customers and makes the world just a little bit better. It’s going to be absolutely awesome."

Phase 3 - Trough of Disillusionment

You're ready to unveil your “baby” to the world. But the world responds far less enthusiastically than you had expected. The downloads, sign ups, and purchases fail to ring in the way you had hoped. And so you struggle to get people to “Add To My Cart”, or otherwise engage with your product or service. Anthony Morgan, Founder of Science Everywhere and Freestyle Social, has some advice, as written by Takara Small:

"Expect a lot of things to go wrong. No one’s road to success is paved in gold. You should expect a lot of problems, because when you expect these things you won’t panic when they rear their ugly heads. I find keeping that mindset helps me remain calm.”

Learning from failure is one of the most important lessons for an entrepreneur. In this video Boyd Reid, Michele Young-Crook, and Sarah Butts discuss their “trough of disillusionment” and what they learned from the experience.

Phase 4 - Slope of Enlightenment

This is the phase where the struggle really begins and when your passion for problem solving becomes most important. At this phase, the only thing that will push your venture beyond the Trough of Disillusionment is your hard work. After all, you’ve put a lot of energy into building a thoughtful business that generates meaningful value for your customers; there must be a way out of this situation. There are no ‘silver bullets’, no easy answers, and each situation is different, but there is hope. Module 3.2 - Launching a Beta Product will cover the tools and best practices for getting your venture off the ground and up the Slope of Enlightenment.

Phase 5 - Plateau of Productivity

The Plateau of Productivity is when your venture has achieved product market fit and is ready to optimize operations and scale growth. That concept will get developed in later modules.

Optional Reading

Farnam Street Blog. “Ben Horowitz: The Struggle.”

Grove, Andrew S. Only the Paranoid Survive!: the Threat and Promise of Strategic Inflection Points.

Cutruzzola, Annemarie “The Realities of Being a 2SLGBTQ+ Entrepreneur”

Small, Takara, “Black in Tech: Startup advice from Black founders who made it”

Section C: Choosing Passion versus Profit and Risk versus Reward

Intrinsic or Extrinsic Motivation

Before launching your venture, you need to understand your motivations for doing so. Specifically, you should consider the extent to which you’re intrinsically motivated or extrinsically motivated? To dive deeper into this concept, read Brad Feld’s blog post on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Extrinsic motivation outcomes, such as money and recognition, can be extremely fickle and difficult to achieve, especially in the earliest days of a new venture when you need sustainable motivation the most. Intrinsic motivations, like passion and problem solving, often sustain entrepreneurs through the difficult times when there is a lack of extrinsic motivators.

While every entrepreneur will possess a mix of motivations, this module makes a case for being intrinsically motivated and passionate about solving your problems as a method for surviving the roller coaster of ups and downs. Please note that being intrinsically motivated is not an absolute law, nor should it be applied to all people or situations.

Co-founder of PayPal and Facebook investor, Peter Thiel, shares his view on motivations from an investor’s perspective, as written by Greg Ferenstein:

“I’m nervous about people who say they want to be an entrepreneur. That’s like saying I want to be rich or I want to be famous. You don’t want to start a business for the sake of it, but because there is a problem that cannot be solved in existing structures.”

What’s Your Passion?

Intrinsic motivations help you stay motivated during hard times, but every company needs profits. This Venn diagram shows the ideal intersection of passion, skills, and being paid for your value creation (meaning there is demand for your skills).

Intrinsic, extrinsic, or a mixture of both? Sinan Mohsin, Nick Baksh, and Tenille Spencer discuss their motivations for becoming entrepreneurs.

Plan

Take a few minutes to fill in this Venn diagram to help identify your motivations.

Risk versus Reward

You will know that, in business and in investing, risk drives return. If you want a big reward, you have to take a big risk. When launching a new venture, aside from the obvious financial risk, you cannot forget the emotional risk which will often display itself through stress.

Read this blog post by Paul Graham, co-founder of startup accelerator Y Combinator, about the pain of the wealth creation process when starting a company.

Pause

Reflect on the following quote from the Paul Graham blog post. Do you agree with this quote? Is this version of entrepreneurship appealing to you?

“Economically, you can think of a startup as a way to compress your whole working life into a few years. Instead of working at a low intensity for forty years, you work as hard as you possibly can for four.”

Section D: What Type of Entrepreneur Are You?

Activity

Take a few minutes to complete the Shopify Survey called “The Founder’s Zodiac: What Type of Entrepreneur Are You?” Once you have completed the survey, read the corresponding link below to learn more about your Founder Zodiac as classified by Shopify.

The Mountaineer: Growth-Minded, Optimistic, and a True Visionary

The Trailblazer: Passionate, Creative, and a Natural Leader

The Cartographer: Reliable, Disciplined, and Obsessed with Detail

The Firestarter: Outgoing, Risk-Taking, and Master of the Pitch

The Outsider: Serious, Consistent, and Skilled at Your Craft

This Shopify survey is very general, but it may help you understand where you sit in the spectrum of entrepreneurial styles.

Pause

Hanna Haponenko, Sinan Mohsin, and Martin Magill reflect on their results from the Founder’s Zodiac survey.

Section E: What’s Your Motivation?

In this module we explore the difficult reality of starting a company and the additional challenges for those from underrepresented communities. This module focuses on intrinsic motivation and passion as a way to survive the ups and downs of the startup roller coaster.

Pause

Take a few minutes to think about the problem you are passionate about and your motivations for wanting to start a company to solve that problem. Here are a few questions to answer:

- Are you intrinsically motivated or extrinsically motivated? List a few of those motivations.

- What are you passionate about?

- How do your skills align with your passion?

Quiz

This module describes the emotional roller coaster you ride when starting a company and suggests some principles for choosing your right approach. This emotional roller coaster represents a natural part of the entrepreneurship process, and you will find other chief executive officers (CEO), founders, and entrepreneurs go through similar experiences.

This module makes a case for being intrinsically motivated and passionate about problem solving as a method for surviving the emotional ups and downs of entrepreneurship.

The module covers the following topics:

- Romanticized CEO versus Reality CEO

- Recognizing The Hype Cycle

- Choosing Passion versus Profit and Risk versus Reward

- What Type of Entrepreneur Are You?

- What’s Your Motivation?

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Identify the ups and downs of being an entrepreneur

- Recall various concepts associated with entrepreneurship

- Discover personal motivations for considering entrepreneurship

Section A: Romanticized CEO versus Reality CEO

Modern media often romanticize startup founders as geniuses, visionaries, or mavericks. While becoming a chief executive officer (CEO), founder, or entrepreneur might offer the biggest buzz you’ve ever felt, entrepreneurship can also be a lonely activity. You may work harder than ever before, but may also spend long hours battling uncertainty. That’s why embarking on this journey requires conviction and passion to both embrace the joys of succeeding in your own business, and to survive both the naysayers and the emotional ups and downs.

To highlight both sides of this perspective, here are two examples:

| Romanticized CEO | Read about the glorification of the entrepreneur. |

| Reality CEO | Read about the realities of being a founder from the perspective of 2SLGBTQ+ entrepreneurs. |

Pause

Boyd Reid, Nick Baksh, and Tenille Spencer give their opinions on the reality of being an entrepreneur and discuss some specific challenges that they encountered on their entrepreneurial journey.

Reality CEO

The job description of a CEO is a bit of a paradox: it’s both simple and complex. A CEO has five main responsibilities:

1. Set & Communicate Strategy

The CEO sets the company’s strategy. Once that strategy gets established, the CEO needs to communicate their strategy clearly to everyone in the company.

Think of the startup as a ship and the CEO as the Captain. The ship and its crew want to sail from a starting point to a destination. The Captain charts the course and communicates the heading to the crew. If the crew misunderstands the direction, however, or worse decides to set their own course, the ship will lie stalled in the water. If it doesn’t sink first….

Authenticity and repetition should become key aspects of how CEO’s communicate to their teams. Great leaders communicate their strategy consistently and often. And if the strategy needs to change, a leader must have the confidence and authority to provide a rationale for this new direction. Ed Catmull former President of Pixar Studios summarized this concept well:

“As long as you have been candid and had good reasons for making your (now- flawed-in-retrospect) decisions, your crew will keep rowing. But if you find that the ship is just spinning around— and if you assert that such meaningless activity is, in fact, forward motion—then the crew will balk.

They know better than anyone when they are working hard but not going anywhere. People want their leaders to be confident. Andrew doesn’t advise being confident merely for confidence’ sake. He believes that leadership is about making your best guess and hurrying up about it so if it’s wrong, there’s

still time to change course.”Ed Catmull, Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration

In the article “Here's the Advice I Give All of Our First Time Founders”, First Round Capital partner, Rob Hayes, says:

“Your job is to get great people and get the best out of them. Even if this makes you uncomfortable, you'll find that really good things happen.”

“As a founder, part of your job is making the rounds and asking people, 'Hey, why are you doing that? How is that going to get us to our goal?' You want to start meaningful dialogues about this, not just so everyone keeps pulling together, but to make sure you're headed in the right direction.”

2. Set & Communicate Values

A company’s values inform its culture, meaning the written or unwritten rules that define how the company sells its products or services, hires its people and works with its customers. Those values are set from the beginning, and are best developed by considering some tradeoffs: Does your company value speed or accuracy? Does your company prioritize customer’s interests over shareholder’s interests?

Regardless of the values your organization lives by, the CEO must communicate these values clearly to their employees. That communication can come from the CEO’s words, but also from the ways they champion the organization's values in their day-to-day conduct; you may find that “lead by example” is both a cliché and a core CEO competency!

As with communicating your company’s strategy, demonstrating authenticity and using repetition can help to communicate your company’s values. For example, Jeff Bezos consistently communicates Amazon’s priority of putting customers’ interests first, above all else. From Bezos’ first shareholder letter in 1997 to today’s Amazon’s leadership principles, the phrase “Customer Obsession” comes up regularly.

3. Manage Finances

Startup research firm CB Insights, after conducting 101 startup post-mortems, highlights one of the reasons why startups fail: they run out of cash. Simply put, the CEO needs to keep cash in the bank account, and they can do this by:

- Leading sales efforts and closing sales

- Raising money from investors

- Managing cash flow and expenses

4. Build the Team

A startup may initially be the idea or passion of one person or a group of co-partners, but eventually entrepreneurs need to recruit people to join in actualizing their company’s vision. Every CEO wants to find, attract, and recruit early team members. Recruiting early team members, however, can create a difficult balancing act of:

- Recruiting people with the right skill sets at the right time needed to move the company forward

- Recruiting people who buy into the vision and align with the culture

- Convincing people to join a startup that is obviously risky, and which lacks the resources of a larger enterprise.

Here are a few quotes from Rob Hayes on early hires and building a team:

- “Growth is all about hiring the people who can give you momentum.”

- “If you hate hiring, hire all your top people right away and then let them do the rest.”

- “Find your lieutenants first.”

- “Start small with hiring — ideally with hires who can take something off [your] plate that [you] really shouldn't be doing.”

- “When you hire amazing people who are better than you at what they do, you look like a genius.”

- “Don't just hire the best; hire the best people for you.”

- “If you don't think you can convince amazing people to work for your company, you've got a much bigger problem.”

- “If you can't convince the people you want that your startup is the best possible opportunity, then you should find something else to do. A lot of founders get caught up in comparing the package they can provide, to compensation elsewhere. But this comes back to finding the right people for you.”

5. Everything else

In the world of startups, the CEO must set strategy, communicate authentically and consistently, manage cash flows, lead recruitment…and simply do whatever is required to ensure the business succeeds. In other words, you might start your day fine-tuning the CRM software, but end the day repairing the copy machine! In this article, “Black in Tech: Startup advice from Black founders who made it” Alexandra McCalla, co-founder of AirMatrix, provides some advice:

“You have to just get in and do the work every day. It’s not glamorous at all. I’ve done everything from filing receipts for the company, filing taxes, making decks, handling the logistics of shipping.”

How to Deal With Challenges

Launching and building a company can be extremely hard, but can also be a lot of fun. Enduring the ups and downs requires staying focused, both on solving problems and on creating value for customers in a way that rewards you financially and personally. Said another way, co-founder of Lifetise, Caroline Hughes shares:

“I’ve rejected the startup dogma that you have to move fast and break things, or always be “crushing it” or “killing it”. I’m doing none of those things. I’m building a thoughtful, empathetic FinTech business from the ground up. It’s slow going.”

Optional Reading

Hayes, Rob. “Here's the Advice I Give All of Our First Time Founders.”

Pinkett, Randal. “Black Faces in White Places”

Hughes, Caroline. “Why I'm Not Crushing It or Killing It in My Startup, and nor Should You.”

Finkelstein, Harley “Our Image of an Entrepreneur Desperately Needs an Update”

Agarwal, Pragya. It Is Time We Acknowledged Loneliness in Entrepreneurs and Did Something about It”.

Abrams, Stacey. “Lead from the Outside: How to Build Your Future and Make Real Change”.

Section B: Recognizing the Hype Cycle

The 1980s rap group, Public Enemy, said it best: “Don’t Believe the Hype.”

Gartner, a research consulting firm, developed the "Gartner Hype Cycle" to chart the development path of new technologies as they are invented and adopted. But the Hype Cycle can also chart the challenges many entrepreneurs experience when launching a new venture. The curve of the Hype Cycle resembles the curvature of a roller coaster drop and involves five phases.

Phase 1 - Innovation Trigger

This is the big bang moment when you have an idea. Everything seems possible and it all feels exciting.

Phase 2 - Peak of Inflated Expectations

You share your idea with friends and family who all support it. You get working on building it.

You pick a name, a logo, business cards, a website, and build a product or service. Your idea becomes a real thing as your excitement builds.

The article “The Struggle” pulls excerpts from Ben Horowitz’s management book “The Hard Things About Hard Things.” Ben Horowitz knows a little bit about how hard it is to build and run a company. Ben co-founded, built, IPO’d, saved from collapse, and sold Opsware for $1.65B. Now he is co-founder of Venture Capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

"Every entrepreneur starts her company with a clear vision for success. You will create an amazing environment and hire the smartest people to join you. Together you will build a beautiful product that delights customers and makes the world just a little bit better. It’s going to be absolutely awesome."

Phase 3 - Trough of Disillusionment

You're ready to unveil your “baby” to the world. But the world responds far less enthusiastically than you had expected. The downloads, sign ups, and purchases fail to ring in the way you had hoped. And so you struggle to get people to “Add To My Cart”, or otherwise engage with your product or service. Anthony Morgan, Founder of Science Everywhere and Freestyle Social, has some advice, as written by Takara Small:

"Expect a lot of things to go wrong. No one’s road to success is paved in gold. You should expect a lot of problems, because when you expect these things you won’t panic when they rear their ugly heads. I find keeping that mindset helps me remain calm.”

Learning from failure is one of the most important lessons for an entrepreneur. In this video Boyd Reid, Michele Young-Crook, and Sarah Butts discuss their “trough of disillusionment” and what they learned from the experience.

Phase 4 - Slope of Enlightenment

This is the phase where the struggle really begins and when your passion for problem solving becomes most important. At this phase, the only thing that will push your venture beyond the Trough of Disillusionment is your hard work. After all, you’ve put a lot of energy into building a thoughtful business that generates meaningful value for your customers; there must be a way out of this situation. There are no ‘silver bullets’, no easy answers, and each situation is different, but there is hope. Module 3.2 - Launching a Beta Product will cover the tools and best practices for getting your venture off the ground and up the Slope of Enlightenment.

Phase 5 - Plateau of Productivity

The Plateau of Productivity is when your venture has achieved product market fit and is ready to optimize operations and scale growth. That concept will get developed in later modules.

Optional Reading

Farnam Street Blog. “Ben Horowitz: The Struggle.”

Grove, Andrew S. Only the Paranoid Survive!: the Threat and Promise of Strategic Inflection Points.

Cutruzzola, Annemarie “The Realities of Being a 2SLGBTQ+ Entrepreneur”

Small, Takara, “Black in Tech: Startup advice from Black founders who made it”

Section C: Choosing Passion versus Profit and Risk versus Reward

Intrinsic or Extrinsic Motivation

Before launching your venture, you need to understand your motivations for doing so. Specifically, you should consider the extent to which you’re intrinsically motivated or extrinsically motivated? To dive deeper into this concept, read Brad Feld’s blog post on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Extrinsic motivation outcomes, such as money and recognition, can be extremely fickle and difficult to achieve, especially in the earliest days of a new venture when you need sustainable motivation the most. Intrinsic motivations, like passion and problem solving, often sustain entrepreneurs through the difficult times when there is a lack of extrinsic motivators.

While every entrepreneur will possess a mix of motivations, this module makes a case for being intrinsically motivated and passionate about solving your problems as a method for surviving the roller coaster of ups and downs. Please note that being intrinsically motivated is not an absolute law, nor should it be applied to all people or situations.

Co-founder of PayPal and Facebook investor, Peter Thiel, shares his view on motivations from an investor’s perspective, as written by Greg Ferenstein:

“I’m nervous about people who say they want to be an entrepreneur. That’s like saying I want to be rich or I want to be famous. You don’t want to start a business for the sake of it, but because there is a problem that cannot be solved in existing structures.”

What’s Your Passion?

Intrinsic motivations help you stay motivated during hard times, but every company needs profits. This Venn diagram shows the ideal intersection of passion, skills, and being paid for your value creation (meaning there is demand for your skills).

Intrinsic, extrinsic, or a mixture of both? Sinan Mohsin, Nick Baksh, and Tenille Spencer discuss their motivations for becoming entrepreneurs.

Plan

Take a few minutes to fill in this Venn diagram to help identify your motivations.

Risk versus Reward

You will know that, in business and in investing, risk drives return. If you want a big reward, you have to take a big risk. When launching a new venture, aside from the obvious financial risk, you cannot forget the emotional risk which will often display itself through stress.

Read this blog post by Paul Graham, co-founder of startup accelerator Y Combinator, about the pain of the wealth creation process when starting a company.

Pause

Reflect on the following quote from the Paul Graham blog post. Do you agree with this quote? Is this version of entrepreneurship appealing to you?

“Economically, you can think of a startup as a way to compress your whole working life into a few years. Instead of working at a low intensity for forty years, you work as hard as you possibly can for four.”

Section D: What Type of Entrepreneur Are You?

Activity

Take a few minutes to complete the Shopify Survey called “The Founder’s Zodiac: What Type of Entrepreneur Are You?” Once you have completed the survey, read the corresponding link below to learn more about your Founder Zodiac as classified by Shopify.

The Mountaineer: Growth-Minded, Optimistic, and a True Visionary

The Trailblazer: Passionate, Creative, and a Natural Leader

The Cartographer: Reliable, Disciplined, and Obsessed with Detail

The Firestarter: Outgoing, Risk-Taking, and Master of the Pitch

The Outsider: Serious, Consistent, and Skilled at Your Craft

This Shopify survey is very general, but it may help you understand where you sit in the spectrum of entrepreneurial styles.

Pause

Hanna Haponenko, Sinan Mohsin, and Martin Magill reflect on their results from the Founder’s Zodiac survey.

Section E: What’s Your Motivation?

In this module we explore the difficult reality of starting a company and the additional challenges for those from underrepresented communities. This module focuses on intrinsic motivation and passion as a way to survive the ups and downs of the startup roller coaster.

Pause

Take a few minutes to think about the problem you are passionate about and your motivations for wanting to start a company to solve that problem. Here are a few questions to answer:

- Are you intrinsically motivated or extrinsically motivated? List a few of those motivations.

- What are you passionate about?

- How do your skills align with your passion?

Quiz

Building a company is hard. It requires long hours and diverse skill sets. Having a co- founder is a common way to share responsibilities, to build complementary skill sets, and to smooth out the emotional ups and downs.

This module will cover the following topics:

- Having a Co-Founder

- Understanding Your Entrepreneurial Function

- Choosing Your Board of Directors, Advisors & Mentors

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Assess the pros and cons of having a co-founder

- Examine the three core skill sets involved with developing a startup

- Identify the roles and responsibilities of various actors in a venture

Section A: Having a Co-Founder

Any friendship or relationship has its pluses and minuses; having a co-founder or business partner is no different.

Consider the following benefits and challenges to having a co-founder.

Benefits

Contribution Of Resources

- Time and energy: Each new partner offers labour, energy and ideas to speed up the venture. Multiple co-founders can also conquer the seemingly endless list of tasks.

- Money or startup capital: Potential co-founders can bring startup capital to cover early expenses.

- Network: Adding co-founders expands your company’s network of potential customers, investors, and employees.

Complementary Skill Sets

The next section covers the variety of skills needed to launch a new venture. For example, engineering, sales, and strategy are the most common skills needed in a venture’s earliest days. It’s rare for one person, however talented and experienced they may be, to have all the necessary skills.

Diverse Perspectives And Opinions

This TechCrunch article highlights the clear benefits of a diverse founding team:

“Diverse teams perform better. First Round Capital found that, over 10 years, teams with at least one female co-founder performed 63 percent better than male-only teams. Racially diverse teams also perform 35 percent better than their industry peers. Yet only 8 percent of venture capital money is going to women-led companies, and 1 percent is going to companies with a black founder. While black and Latina women in particular are behind 80 percent of new female-led companies, they capture a meager .2 percent of VC funding.”

Pause

Sharing Responsibilities, Decision Making & Stress

As discussed in the last module - The Start Up Roller Coaster - getting a company off of the ground can be a lonely, difficult and stressful process. Many entrepreneurs succeed on their own, but having a partner can make the process a lot easier.

A partner can help with decision-making. You may think your idea or strategy is the greatest ever, but smart entrepreneurs know the benefit of a second set of eyes, ears and thoughts. Having a partner helps vet ideas and strategies to ensure the approach is well thought out and sound.

Make no mistake, however: deciding to work with a partner or co-founder differs from hiring a senior employee. With a senior employee you give direction and monitor performance; with a partner you share responsibilities, decision-making, successes and, yes, stress. Senior employees, no matter how dedicated or skilled, don’t share the full emotional stress of running a business.

Investors Often Favour Teams

For the reasons mentioned above,professional investors often favor investing in teams rather than solo-founders. This isn’t a law; solo-founders can successfully raise outside capital, but often with more difficulty.

Review this TechCrunch article by Haje Jan Kamps which provides two viewpoints, breaking down the data to show that solo-founders have been more successful in raising capital and selling their ventures than larger founding teams, while recommending having a co-founder.

Hanna Haponenko, Sarah Butts, and Martin Magill share their opinions on the many advantages of having a co-founder.

Challenges

Differences In Values & Communication Styles

Partnerships, like any relationship, can expose differences in opinions, values, motivations, work styles, and communication styles. When looking for a partner on a new venture these differences need to be discussed as early as possible.

Review this article from Crunchbase by Sami Rusani and consider the tricks it outlines for assessing a new partner.

Commitment To The Venture

Another common source of tension: differences in each partner’s commitment. This difference in commitment can arise from waning interest in the project, pressing family commitments, or differences in motivation and values.

Co-founders can make your business succeed. When choosing a co-founder, however, you need to choose right the first time, as Paul Graham shares:

“Co-founders are for a startup what location is for real estate. You can change anything about a house except where it is. In a startup you can change your idea easily, but changing your co-founders is hard.”

Having a co-founder can have its disadvantages as well. Hanna Haponenko, Sarah Butts, and Boyd Reid share their insights on some of the disadvantages of having a co-founder.

How to Know if it Will Work With Your Co-Founder

In a lot of ways, having a co-founder is like being married. You make a multi-year commitment to a partnership to share in the responsibility, stress, and ups and downs. You will spend a lot of waking hours with your partner and you will need to get along for the sake of the company. Here are a few areas to explore with a potential partner before becoming committed to each other.

- What are their motivations for starting a company? Are they intrinsically motivated to solve a problem, or are they extrinsically motivated by money?

- What is their vision for the venture? Do they want to create a small company that sustains their lifestyle, or do they want to build a billion dollar company?

- How do they like to work and communicate? A company’s culture is set from the top, built on the values held by the founding team. It’s important for partners to align their values in the earliest days of the company.

- When determining what the company values in order to determine how it gets work done, it’s best to prioritize some values over others. For example, does the company value speed over accuracy?

Airport Rule

Picture yourself stranded in an airport, seated next to your partner or co-founder for 24 hours straight. How might that day play out? Could you get along for long periods of time, in close contact, during stressful times?

Finding a Co-Founder

Analogous to marriage, there is no easy solution or formula for finding the right partner. Co-founding often happens in a very organic way, as two or more people come together around a common goal or set of values. Also like marriage, it is best to move slowly through this process; maybe you need to “date” first before you jump into the venture?

There is no perfect solution for finding a partner, but there are services to assist in corporate matchmaking like the CoFoundersLab.

Optional Reading

Farley, Shannon “Why we need diverse founder and funding teams and how to find them”

Hellstern, Meghan, and Kim de Laat “Growing Their Own Way: High-growth women entrepreneurs in Canada

Section B: Understanding Your Entrepreneurial Function - Hipster, Hacker, and Hustler

When starting a new venture it is important to consider the three core functions of a successful business: determining the business strategy, building the product or service, and selling the product or service. These three core functions often fall into these early job titles:

- Set the vision of the company - Chief Executive Officer (CEO)

- Build the product or service - Chief Technology Officer (CTO)

- Sell the product or service - Chief Revenue Officer (CRO) or VP Sales

In modern startup culture these three functions have been coined the Hipster (design), Hacker (engineering), and Hustler (sales and strategy).

Review this Forbes article written by Andy Ellwood which dives deeper into the Hipster, Hacker, and a Hustler concept.

In reality, the three job functions can be split across two people. For example:

- Product or service focused CEO: Job 1 and 2 can be done by the same person - think Mark Zuckerberg

- Sales focused CEO: Job 1 and 3 done by the same person - think Steve Jobs

Pause

Section C: Choosing Your Board of Directors, Advisors, and Mentors

It takes a village to build a startup, and advisors form a big part of a startup’s development. This might include a Board of Directors or Board of Advisors.

Board of Directors

When you incorporate a company you need to define your corporate legal structure: namely your Shareholders, Board of Directors, and Management. A board of directors has a fiduciary responsibility to act on behalf of the shareholders in governing the overall enterprise, and in overseeing the management team. The CEO reports to the board of directors during regular board meetings.

When a startup is incorporated, the shareholders, board members and founding team may be one and the same. It’s often much later in the startup’s life, perhaps at the stage of fundraising from external investors (e.g. Series A financing), that the board of directors becomes formalized with regular meetings and structure. At this later stage, investors and seasoned independent advisors may be added as board members.

Board of Advisors

A board of advisors serves as an informal group of advisors and industry experts that provides guidance and advice to the management team; such advisors can also open doors to key industry leaders. Often these advisors offer years of experience in a specific field, or can fill skill sets missing in the founding management team. A board of advisors is, however, not part of the corporation’s legal structure.

What to Look For in Advisors

When asked to provide advice, many mentors, advisors, and coaches often tend to provide their opinions on which market to tackle, or what product or service-features to build. Advisory opinions, however, can cause a few problems:

- Unless the advisor has built this exact type of business before, they will never know your business better than you do.

- Advice from multiple advisors can conflict, leaving the founder confused on which advice to follow.

- Opinions disguised as advice are still opinions, not facts. No matter the opinion expressed, it represents only one data point in a spectrum of perspectives.

Surrounding yourself with the right people is crucial to the success of your business. In this video Boyd Reid, Nick Baksh, and Michele Young-Crook share what characteristics they look for in mentors, investors and co-founders.

The best advisors respect the founder’s depth of knowledge of their own business, and provide the founder with disciplined thinking and sound logic; they often prove useful in challenging and validating the founder’s assumptions when helping to make decisions.

Quiz

Building a company is hard. It requires long hours and diverse skill sets. Having a co- founder is a common way to share responsibilities, to build complementary skill sets, and to smooth out the emotional ups and downs.

This module will cover the following topics:

- Having a Co-Founder

- Understanding Your Entrepreneurial Function

- Choosing Your Board of Directors, Advisors & Mentors

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Assess the pros and cons of having a co-founder

- Examine the three core skill sets involved with developing a startup

- Identify the roles and responsibilities of various actors in a venture

Section A: Having a Co-Founder

Any friendship or relationship has its pluses and minuses; having a co-founder or business partner is no different.

Consider the following benefits and challenges to having a co-founder.

Benefits

Contribution Of Resources

- Time and energy: Each new partner offers labour, energy and ideas to speed up the venture. Multiple co-founders can also conquer the seemingly endless list of tasks.

- Money or startup capital: Potential co-founders can bring startup capital to cover early expenses.

- Network: Adding co-founders expands your company’s network of potential customers, investors, and employees.

Complementary Skill Sets

The next section covers the variety of skills needed to launch a new venture. For example, engineering, sales, and strategy are the most common skills needed in a venture’s earliest days. It’s rare for one person, however talented and experienced they may be, to have all the necessary skills.

Diverse Perspectives And Opinions

This TechCrunch article highlights the clear benefits of a diverse founding team:

“Diverse teams perform better. First Round Capital found that, over 10 years, teams with at least one female co-founder performed 63 percent better than male-only teams. Racially diverse teams also perform 35 percent better than their industry peers. Yet only 8 percent of venture capital money is going to women-led companies, and 1 percent is going to companies with a black founder. While black and Latina women in particular are behind 80 percent of new female-led companies, they capture a meager .2 percent of VC funding.”

Pause

Sharing Responsibilities, Decision Making & Stress

As discussed in the last module - The Start Up Roller Coaster - getting a company off of the ground can be a lonely, difficult and stressful process. Many entrepreneurs succeed on their own, but having a partner can make the process a lot easier.

A partner can help with decision-making. You may think your idea or strategy is the greatest ever, but smart entrepreneurs know the benefit of a second set of eyes, ears and thoughts. Having a partner helps vet ideas and strategies to ensure the approach is well thought out and sound.

Make no mistake, however: deciding to work with a partner or co-founder differs from hiring a senior employee. With a senior employee you give direction and monitor performance; with a partner you share responsibilities, decision-making, successes and, yes, stress. Senior employees, no matter how dedicated or skilled, don’t share the full emotional stress of running a business.

Investors Often Favour Teams

For the reasons mentioned above,professional investors often favor investing in teams rather than solo-founders. This isn’t a law; solo-founders can successfully raise outside capital, but often with more difficulty.

Review this TechCrunch article by Haje Jan Kamps which provides two viewpoints, breaking down the data to show that solo-founders have been more successful in raising capital and selling their ventures than larger founding teams, while recommending having a co-founder.

Hanna Haponenko, Sarah Butts, and Martin Magill share their opinions on the many advantages of having a co-founder.

Challenges

Differences In Values & Communication Styles

Partnerships, like any relationship, can expose differences in opinions, values, motivations, work styles, and communication styles. When looking for a partner on a new venture these differences need to be discussed as early as possible.

Review this article from Crunchbase by Sami Rusani and consider the tricks it outlines for assessing a new partner.

Commitment To The Venture

Another common source of tension: differences in each partner’s commitment. This difference in commitment can arise from waning interest in the project, pressing family commitments, or differences in motivation and values.

Co-founders can make your business succeed. When choosing a co-founder, however, you need to choose right the first time, as Paul Graham shares:

“Co-founders are for a startup what location is for real estate. You can change anything about a house except where it is. In a startup you can change your idea easily, but changing your co-founders is hard.”

Having a co-founder can have its disadvantages as well. Hanna Haponenko, Sarah Butts, and Boyd Reid share their insights on some of the disadvantages of having a co-founder.

How to Know if it Will Work With Your Co-Founder

In a lot of ways, having a co-founder is like being married. You make a multi-year commitment to a partnership to share in the responsibility, stress, and ups and downs. You will spend a lot of waking hours with your partner and you will need to get along for the sake of the company. Here are a few areas to explore with a potential partner before becoming committed to each other.

- What are their motivations for starting a company? Are they intrinsically motivated to solve a problem, or are they extrinsically motivated by money?