4 Chapter 4: Recognizing Needs and Opportunities

Chapter 4: Recognizing Needs & Opportunities

Chapter 4 Introduction[1]

How can we make the floors cleaner? That’s the question that Proctor & Gamble asked its chemists.[2] Years of working on this problem, however, yielded no improved cleaning solution.

So Proctor & Gamble took a different approach and hired a design firm.[3] Rather than focusing on chemical improvements, the designers watched people clean. Observations uncovered the real problem: mops. People spent more time cleaning their mops than they did cleaning their floors. The mop was an ineffective tool for the task at hand.

This insight led to the development of the Swiffer—a billion-dollar product line for Proctor & Gamble. The lesson learned is that innovation isn’t simply about asking the right questions; it also involves framing questions differently. Our approach to problems is affected by the manner in which they are presented. To the chemist, a cleaner floor was a scientific problem, while to the designer it was a human problem.

It’s vital that we be able to shift perspectives when we need to generate different types of results. If our thinking is too narrow, then we may miss breakthroughs. How we formulate problems is just as important as how we solve them. In fact, our ability to discover and translate problems may well be the most significant step toward realizing innovation.

The Art of Problem Discovery

We’re all problem solvers. Every day we deal with unexpected issues commanding our attention. We fix things when they break and correct errors when we detect them. We answer tough questions and make difficult decisions.

It’s also important to draw attention to how we think about problems: how we can discover and convert them into new strategic initiatives. Often, we jump prematurely into problem solving mode before fully exploring the wide range of possibilities.[4] This oversight can ultimately generate solutions that are good enough, but not as good as they could be.

Just to be clear, the problems that ambitious innovators should aim to solve are not mere operational, day-to-day issues – but rather those that can enact systematic disruption.[5] The world is being reshaped right before our eyes. Many things we do today won’t be necessary tomorrow. Likewise, there are many things that we’re not doing that we’ll need to learn. Leaders taking a problem-oriented perspective will be well positioned to discover what’s necessary and to empower their organizations and communities to evolve more effectively. The frameworks and practices described in the following pages are intended to assist in identifying potential growth areas, which can be referred to as the art of problem discovery. By seeking out needs, problems, and aspirations within our communities, we can apply empathic measures toward success. Each community is unique, so we need to leverage tools for addressing local situations.

What is a Problem?

The problem-solving literature offers many definitions, but for our purposes: problems are “questions raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution.”[6] Our pursuit is to seek better questions. Questions with impact. Questions that help us identify obstacles.

Problem discovery entails looking for ways around barriers. Good questions are our currency. They help us investigate the unknown and point us in new directions. But not all problems are equal. Some are presented to us, while others are discovered or created.[7] It’s important that we know the difference so we can engage productively:

- Presented problems tend to be ones that have been encountered before, such as the process of picking a movie or completing an application. What information would you need to perform that task?

- Discovered problems are self-initiated. Imagine that noisy student groups start using the quiet reading room in the library. Other may view them as a nuisance, but you ask: Why? What factors have led to this issue?

- Created problems are ones we invent. For example, an entrepreneur decides to develop a mobile app to capture all local recreation activities. What functionality should it have? What should the user experience be like? The act of creating something new presents a series of questions that need to be examined.

Different problems require different actions. The way they are framed potentially limits or broadens our response. Problem discovery, more than anything else, is an attitude driven by curiosity and empathy: How can we learn more so that we can do more for our users? Problems are valuable in challenging us to confront business-as-usual thinking and to imagine what else is possible. In this sense, problems are a growth strategy.

Problems as Products

Problem discovery encourages us to probe around the fringes rather than to stay confined within conventional limitations. During this stage of ideation, we operate as designers visualizing numerous options. In this manner, problems become products waiting to be shaped.

Our objectives (e.g., a partnership, a website, a process) represent things that we can accomplish. Each of them includes a sequence of questions. By treating problems as products-in-development, we can apply various strategies to help determine the necessary tasks. Sometimes this effort is straightforward, and other times more complex. For instance, a relationship with a particular supplier might begin with an initial meeting to gauge their capabilities, whereas interviewing various stakeholders about their needs will likely require a series of steps.

While having clear objectives helps to structure strategies, sometimes the outcome isn’t well defined. For example, the Swiffer designers started out by watching people clean. They didn’t begin with the goal of reinventing the mop; that insight had to be discovered.

Innovation thought leader Clayton Christensen encourages innovators to consider the job-to-be-done point of view.[8] From this perspective, products and services should revolve around enabling people to accomplish specific tasks. For example, an online instruction platform could provide students with basic research skills on-demand – but the job is to help them write papers more effectively and efficiently.

Although many aspects influence the product development cycle, the key takeaway is acknowledging that there are some things that we just don’t know. Accepting that, we design a learning process to fill those knowledge gaps.[9] The objective is to move our thinking from hunches toward more viable and actionable directions.

It is helpful to divide the product development process into three distinct stages.[10]

- Incubation

- Preparation

- Production

Each stage requires a different attitude, perspective, skillset, and objective. Incubation defines the discovery period when different ideas are gathered and explored. During the preparation phase the most intriguing ideas are shaped into full concepts. Through greater structure and application, we figure out what’s needed to make it happen. The production phase transforms vision into reality.

Problem Designers

When Ron Hickman pitched the idea of a portable workbench, everyone turned him down. There wasn’t a perceived need. So Hickman took his prototypes to trade fairs where the demand was overwhelming. Black & Decker eventually bought in and marketed the WorkMate, consequently selling over 30 million benches to date.[11]

Not everyone can see problems. In fact, one of the biggest mistakes is to assume that problem solvers should also be problem seekers who find and frame new possibilities.[12] People focused on daily operations may be too entrenched to perceive or desire new directions.

Startup guru Eric Ries believes that organizations should employ two core teams: problem finders and problem solvers.[13] One group remains on the lookout for what’s wrong or what’s missing, and the other group is devoted to addressing the necessary changes. The skill, attitudes, and workflows vary greatly among these functions. An interface designer typically doesn’t code the backend of a website. And an electrician usually won’t design blueprints. A great problem solver isn’t necessarily a great problem discoverer.

Economist William Easterly places this notion in context by suggesting that we need to function as searchers instead of as uninformed planners.[14] The planner presumes to know the best way to address problems, while the searcher admits that they don’t know the answers in advance and therefore commits to pursuing solutions through trial and error.

Searchers focus on specific tasks and test the effectiveness of different approaches, making adjustments along the way. Alternately, planners adhere to fixed objectives and work to achieve the plan as it was prescribed.

Growth-oriented leaders have different objectives than leaders focused on sustaining traditional operations. They push out in new directions, not settling for a static sense of excellence. The innovative leader doesn’t aspire to give users only what they want, but rather aims to discover what they need and then designs solutions that will help advance those interests. The art of discovery is a continual search for the next step.

Thinking Lenses

Astronomers use a technique known as averted vision for viewing faint objects.[15] Instead of observing something directly, they glance slightly to the side. This method enables them to see the item more completely. The same technique can be applied to viewing problems. If we look at them head-on, they may appear too familiar or too foreign for us to fully comprehend. Instead, we need to gaze across the surrounding landscape.

As stated earlier, how we frame problems impacts the way that we think about solutions. To do this effectively we need to apply adaptive thinking – knowing when and how to use different models to accomplish different tasks. Although we often praise critical thinking, at the early stages of problem discovery and ideation, this method actually can be harmful. Rather than dissecting ideas through critical analysis, we need to embrace the designer’s mindset of crosspollination and synthesis.[16] Here are a few “thinking lenses” to expand our perspective.

Systems Thinking [17]

A systems lens broadens our view. It propounds that all distinct components operate together to form a cohesive, interconnected whole. A commonly referenced example is an automobile, in which the brakes, tires, engine, steering wheel and so forth work collectively to propel the vehicle. If one piece fails, then it cannot function properly.

In terms of problem discovery, systems thinking provides a powerful visioning tool. Innovators can observe patterns across processes rather than getting mired in tiny details. From the systems vantage point they can detect issues, adjust procedures, or uncover previously unrealized opportunities.

Design Thinking [18]

This lens enables us to see through the eyes of our users. Similar to systems thinking, design thinking encourages us to examine the total experience beyond individual transactions. Visiting Starbucks is more than just getting coffee; it’s a distinct encounter where the service is choreographed, and a mood is calibrated.

Design thinking is rooted in empathy. By seeking to understand what people are trying to accomplish, we become better positioned to help them succeed. This variant of human-centered design incorporates behaviors into the process. Minimizing users’ frustrations or confusions amplifies the utility, and thereby the desirability of a product or service. The Swiffer team used design thinking to study the cleaning experience and then turned that insight into a better tool for the task.

As a methodology, design thinking emphasizes solutions-based thinking, beginning with an intended goal rather than a specific problem. For example: Cleaner floors. This process (outlined below and illustrated in Figure 4.1) differs from the classic scientific method, which defines the parameters of the problem and then tests the hypothesis. Instead, design thinking starts with the desired outcome and then works backwards. Amtrak offers a good case study.[19] The train line wanted to revamp the interior of their passenger cars to attract new customers. Their design firm, however, urged them to consider the totality of all customer touch points, from purchasing tickets to waiting in the station to boarding and disembarking. Fancier furniture alone wasn’t enough; instead, Amtrak needed to reinvent the train riding experience.

Complexity is key to design thinking. Straightforward problems that can be solved with enough money and force do not require much design thinking. Creative design thinking and planning are about finding new solutions for problems with several tricky variables in play. Designing products for human beings, who are themselves complex and sometimes unpredictable, requires design thinking.

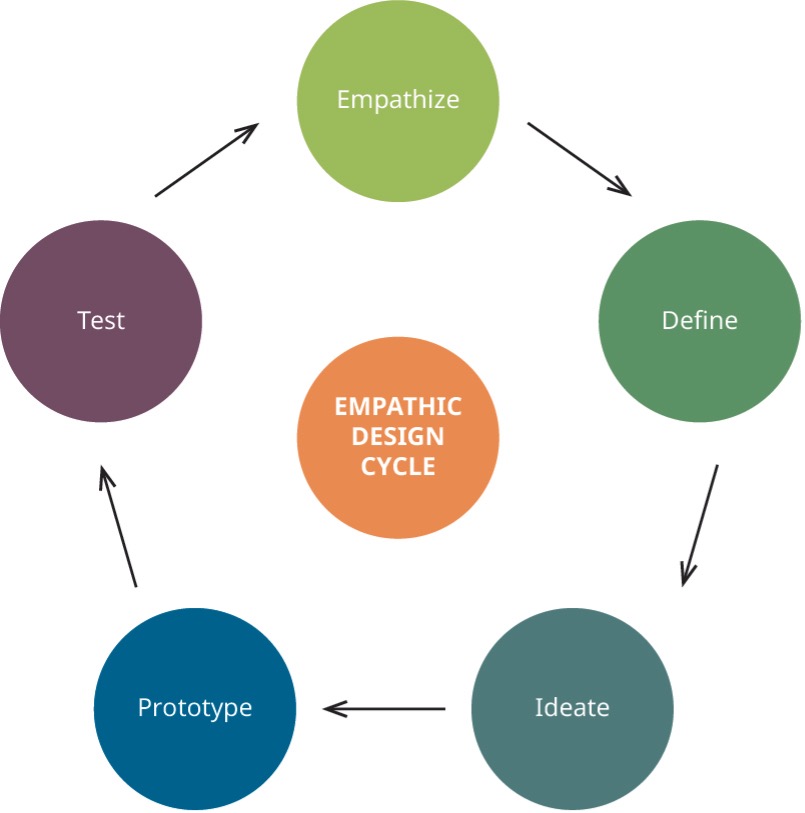

The design thinking process consists of five (non-linear) steps:

- Accessing and expressing empathy. Empathy is essential to beginning a process of human-centric design. Practicing empathy enables us to relate to people, see the problem through their eyes, and understand the feelings of those who experience it. By expressing empathy, you can begin to understand many facets of a problem and start to think about all of the forces you will need to bring to bear on it. Empathy sets the stage for the second step.

- Defining the problem. Defining the problem must be based on honest, rational, and emotional observation for human-centric design to work.

- Ideating solutions (brainstorming). Third in the process is brainstorming solutions. We will delve more deeply into brainstorming, what it means, and how you can brainstorm creatively beyond the basic whiteboard scribbling when we get to generating solutions.

- Prototyping. After ideation, you will build low quality versions of your potential solutions, often with cheaper materials and/or easier to create mockups of how it works.

- Testing. At this point, you will vet your ideas and prototypes with customers/users by bringing your prototype back to them for feedback. This stage helps you gain a deeper understanding of your users and their needs, in order to improve your designs.

Figure 4.1 The empathetic design cycle is human-centric. (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Figure 4.1 The empathetic design cycle is human-centric. (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

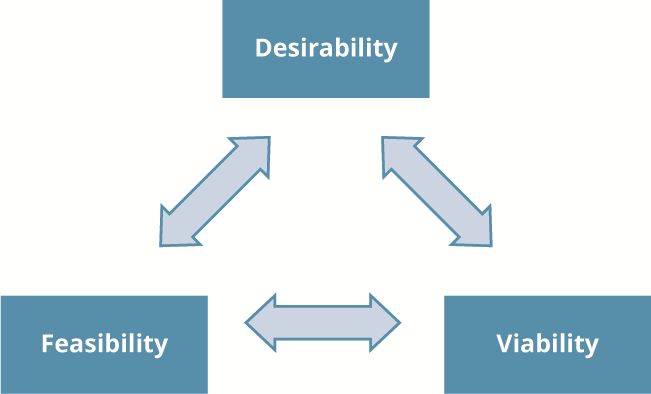

Again, it must be stressed that design thinking is a non-linear process. In other words, you may iterate multiple times and go back and forth between steps on your journey toward developing a solution that meets the three criteria for solutions in design thinking:

- Desirability: How desirable is the idea? Will customers use it, and why?

- Feasibility: How feasible is this idea? What are the costs of making it? How practical is the concept?

- Viability: Will this idea be viable? How will it be sustained over time (i.e., through revenue generation)?

Figure 4.2 Design thinking criteria of desirability, feasibility, and viability. (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Integrative Thinking [20]

This lens enables us to combine diverse ideas into a more cohesive concept. Integrative thinking aims to synthesize positive components, while minimizing negatives. The objective is to develop togetherness and to avoid wholly accepting one outcome at the expense of others.

For example, imagine that the university library is considering merging various reference desks into a single service point. They might be exploring alternative options such as roving assistants or kiosks – and each alternative will have obvious pros and cons. Instead of selecting one over the other, an integrative approach endeavors to combine them and offer a different resolution.

A benefit of this approach is that it shifts thinking away from positional battles toward developing shared interests.[21] Reaching a mutually desired outcome (e.g., what’s best for users), becomes the target, rather than satisfying personal preferences. The integrative framework prioritizes the most relevant aspects and separates the less critical ones. Attention focuses on challenging assumptions and measuring their validity. The objective here isn’t to compromise, but rather to establish a foundation for a more robustly imagined model.[22]

Lateral Thinking [23]

This lens empowers us to generate novel and unexpected ideas. Whereas traditional “vertical” thinking carries ideas forward through a predictable analytical process, lateral thinking challenges the status quo. It constitutes both a mindset and a series of techniques aimed at disrupting routine thinking by searching for different types of ideas, solutions, or problems.

Lateral thinking distances itself from critical thinking, which is arguably concerned with judging value and seeking errors. Contrarily, lateral thinking directs the movement of ideas in multiple directions. A sampling of methods:

- Alternatives: Imagine different ways of doing things. For example, recall Stephanie Phillip’s challenge to students after her presentation: “What if there wasn’t a landfill?” The focus isn’t on “why we need a landfill,” but instead on visualizing other solutions that could emerge.

- Whitespace: Focus on areas where no one else is looking. As you consider your surroundings, stay alert to things that are missing or previously unarticulated problems. For example, imagine you learn that students studying in the library at night don’t want to lose their seat. What if the library café offered an occasional cart service bringing snacks to hungry patrons?

- Challenges: Break from the limitations of current practices. This tool is designed to ask the question “why?” in a nonthreatening manner. Challenging existing values, operations, and processes pushes us to consider new opportunities. Why are glass recycling and organics not collected in many neighborhoods and municipalities? By exploring a challenging line of questioning, we may find that some materials could be collected elsewhere, or we may consider the value of on-demand collection.

Agile Thinking [24]

An agile lens enables us to modify concepts while projects are in motion. As we learn more about what needs to be done or what else might be possible, we can adapt our initial plans. Agile derives from software development and describes both a mindset and a method that encourages iterative development. Objectives and requirements are expected to evolve, enabling partners to contribute towards a better outcome.

A benefit to this type of thinking is that it minimizes reliance on assumptions and instead embraces a discovery-oriented position to quickly address needs or issues that surface. With everyone on the same page, it invites creativity and establishes a tone of always being on the lookout for appropriate changes.

Computational Thinking [25]

This lens enables us to analyze processes for unrealized opportunities. Computational thinking draws from computer science techniques that apply algorithmic methods to finding, defining, and solving problems. This mode is less concerned with generating solutions than with determining the sequence of steps necessary for a particular outcome.

Let’s say that you want to add a new feature to your company website. Computational thinking would be used to envision what needs to be coded line by line. This thinking style, however, extends beyond software development to diverse tasks such as writing a proposal or launching a fundraising campaign. Each of these objectives requires a sequence of tasks to be performed in an optimal order — essentially, an algorithm.

Computational thinking helps us determine not only what information is necessary, but also that which is missing. It encourages a hacker mentality, in creating new possibilities or reviewing existing processes for better efficiencies, anomalies, vulnerabilities, and other correlations. In the circular economy problem area, examples might include examining city waste collection/disposal procedures or reviewing existing nonprofits to identify potential collaboration opportunities.

Practices

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark crossed the continent with commercial, military, and political goals in mind. Yet the overarching objective of their expedition was gleaning an accurate sense of the resources and character of the West– to acquire new knowledge.

To undertake their discovery-based mission, they received training in geography, astronomy, ethnology, climatology, mineralogy, meteorology, botany, ornithology, and zoology prior to the trip.[26] Over the course of their journey, they generated 140 maps and gathered scientific information on over 200 plants and animals.

The compelling aspect of Lewis and Clark is their preparation. How did they plan for the unknown? Traveling for two years across 7,000 miles of wilderness, they had to be agile thinkers, adapting to the environment they encountered.

Startup companies encounter a similar process. Taking an idea from concept to implementation and building a successful enterprise is a challenging journey with unexpected pivots along the way. Entrepreneurs often refer to innovation as a mindset not a toolset.[27] While numerous techniques and methodologies can be applied to finding and solving problems or developing ideas, there’s no magic bullet.

Designer, hacker, anthropologist, and product developer: our roles as leaders require us to wear multiple hats.[28] Different problems require different approaches, and we need to be able to adapt thinking styles accordingly. Problem discovery isn’t a one-size-fits-all process. Our cities have unique cultures and varying tolerances to change. Our communities are all slightly different, and therefore our efforts must be adjusted appropriately. Below you will find a collection of practices to inspire your thinking.

Search for Better Questions

Start by asking all the obvious questions.[29] Get the easy stuff out of the way in order to make room for the more difficult or hidden possibilities. Once a concept has been defined you can push beyond what is predictable and into more imaginative directions. Two of the most powerful questions a leader can ask are “Why?” and “What if?” Why are we doing this? Why is this method effective? Why does this matter? What if we try something new? What if we changed the model? What if we stopped doing this?

To spark innovation we need to think differently. Asking thought-provoking questions can lead to novel concepts that push our creativity. It is vital that we can confidently free ourselves from conventional thinking and indulge divergent paths. Here are three frameworks to help us ask better questions.[30]

- Challenges: How can we produce a novel good/service with only existing materials?

- Provocation: What if we only purchase/consume resources as they are needed?

- Achievement: What steps do we need to take to become a zero-waste city?

Simply asking the right questions doesn’t go far enough. Innovation-minded leaders should be conscious of developing a questioning culture – fostering an environment where questions are linked to growth rather than criticism.[31] Our intention should be to cultivate the learner mindset: optimistic, curious, and open to new possibilities. This mode contrasts with the judger mindset, defined as reactive, protective, and skeptical of change. Questions can be our greatest assets or the things holding us back.

Our quest should always be one for better questions—those that will enable us to gain a richer understanding, consider alternatives, or reach for new insights. The best questions add value and lead us in unexpected directions.

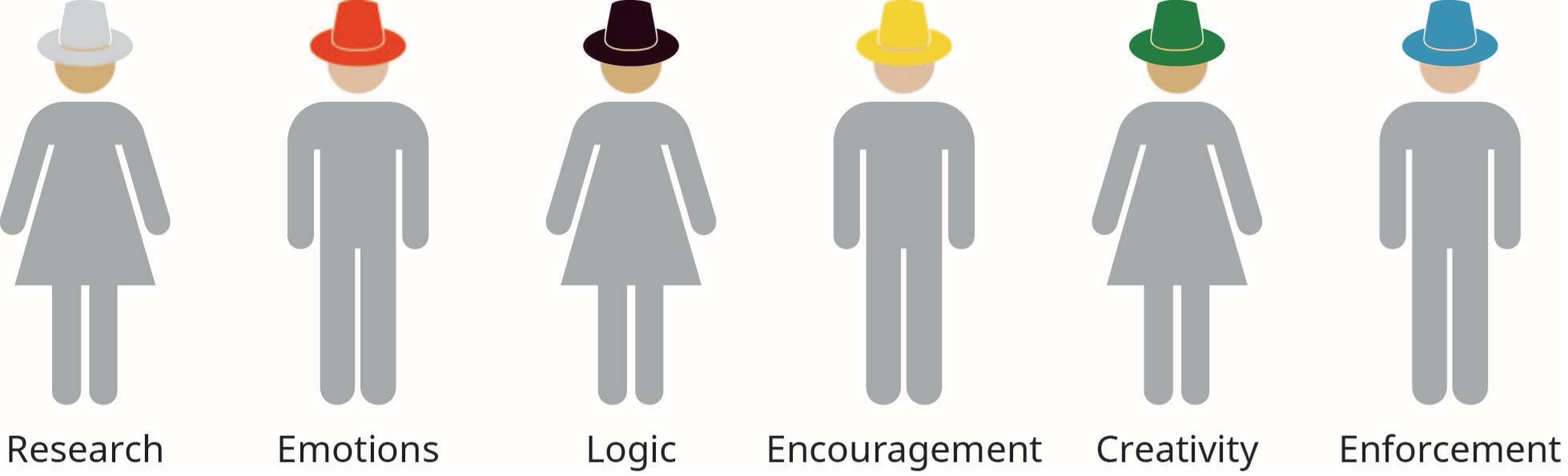

Change Your Thinking Cap

Questions aren’t the only things that get us thinking differently; sometimes we have to challenge ourselves more deliberately. The benefit in this is that it enables us to appreciate a wider perspective. The Six Thinking Hats [see Figure 4.3] structure offers a guide for leading ideation sessions.[32] The framework isn’t scripted, but it establishes roles for more conscientious engagement.

- Blue Hat: The moderator. The Blue Hat frames the process, maintains the broader structure of the discussion, and may set the terms by which progress will be judged. They make sure the other hats play by the rules or stay in their respective “lanes”.

- White Hat: The objective perspective. The White Hat is concerned with facts and figures and acts as information gatherer by conducting research and bringing quantitative analysis to the discussion.

- Red Hat: The emotional perspective. The Red Hat brings raw emotion to the mix and offers feelings without having to justify them.

- Black Hat: The critical perspective. The Black Hat (also known as the “devil’s advocate”) employs logic and caution and warns participants about institutional limitations.

- Yellow Hat: The optimistic perspective. The Yellow Hat brings the “logical positive” of optimism to the group and encourages solving small and large problems.

- Green Hat: The creative perspective. The Green Hat introduces new ideas and change and may provoke other members when needed.

Figure 4.3 The Six Thinking Hats exercise is designed to have each participant focus on a particular approach to the problem or discussion. (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Figure 4.3 The Six Thinking Hats exercise is designed to have each participant focus on a particular approach to the problem or discussion. (Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

There are different versions of this ideation game, but all of them are quite useful for encouraging thought by limiting the mindset of those involved in the game. One way to use this system is to assign participants a particular hat for a set period of time. For example, when a new idea is being discussed, everyone is encouraged to offer yellow-hat thinking as an effort to explore all the positive attributes. The moderator could then ask everyone to switch to green hats in order to talk about how the concept might take shape. Being encouraged to embody one mode of thinking frees you from considering other aspects of a problem that can limit creativity when you are looking for a solution.

Another way to use this approach is to assign each participant to a specific hat. By being responsible for only one mode of thinking, participants can fully advocate for that point of view and can think deeply about that particular aspect of the solution. Thus, the group can be deeply creative, deeply logical, deeply optimistic, and deeply critical. This practice is meant to move groups past surface-level solutions. If you practice this exercise well, the challenges of implementing it are well worth the effort. It gives you the opportunity to vet ideas thoroughly while keeping many personality clashes at bay. If the participants stay in character, they can be accused only of acting in the best interests of their hat.

This tool is helpful for facilitation, because it directs the conversation toward one aspect at a time, rather than going off on too many tangents. Moderators can also ask people to switch their thinking. Therefore, if a teammate is too emotionally invested (red hat) or overly critical (black hat), he could be redirected from distracting a productive conversation. This ability to steer attention is a powerful practice for leaders. It enables you to keep people focused and establish a comprehensive view of the topic at hand.

Ethnography

Ethnography and other sociological methods have become widespread in design thinking other discovery techniques. This reflects a trending away from satisfaction surveys toward observational and behavior studies seeking to uncover unexpressed or unmet user needs.[33] Ethnography and related techniques can jumpstart your design thinking process. Like the Swiffer design team’s observations of people cleaning, these types of interactions with potential customers and users can help bolster our empathic insights and pinpoint areas of potential growth.

Affinity Groups

Focus groups are powerful discovery tools. Structured conversations with users (or non-users) provide rich data. They can also help to unravel delicate or tricky instances of service failures, miscommunications, or other missed opportunities. When moderated effectively, focus groups are a valuable instrument for provoking new insights, validating perceptions, and exploring lateral thinking.[34]

Affinity groups are a useful focus group technique.[35] Participants are given a broad topic such as: What does the ideal dining experience look like? Describe the most enjoyable vacation you’ve ever taken. How does waste impact your life? Using sticky notes, participants work on responses independently and are occasionally given prompts to ignite their thinking. The goal is to capture as many ideas as possible. The activity then shifts into a collaborative effort with participants, combining all their ideas and adding new ones as they sort them into similar categories. Finally, a follow-up conversation takes place about the concepts and their thinking throughout the process.

Focus groups might not always provide the answers we need for breakthrough ideas, but they can help us discover additional questions to explore using other methods.

IDEO’s Discovery Process

IDEO is a premier design and innovation consultancy firm. They have developed many products that we use every day. IDEO employs a variation of design thinking that can be applied beyond the practices of business or product development. In fact, they created a toolkit specifically for educators, walking them through its innovation methodology.[36]

The process includes five phases: Discovery, Interpretation, Ideation, Experimentation, and Evolution. IDEO encourages human-centered, outcomes-based exploration. For example, “How do we help students thrive?” is a different question from the metrics-based “How do we raise test scores?”.

IDEO recommends starting out with broad questions posed as aspirational challenges. How might learning spaces be better designed to meet students’ needs? How do we create a 21st century learning experience for students? Their process then works toward achieving each goal.

While the full framework is beyond our scope, the IDEO toolkit offers a practical guide for ideation and development. Whether you are considering something tactile such as a mobile app or product or a more process-oriented offering like a new service, IDEO’s methods can help you advance your understanding of needs.

Concluding Comments on Problem Discovery

Many astronauts experience a phenomenon known as the overview effect, a cognitive shift in awareness while viewing Earth from orbit.[37] They report a profound sense of interconnectedness: seeing our planet as an ecosystem rather than just the place they live.

Pushing ourselves outside of traditional boundaries can have a similar impact on our self-awareness. Our day-to-day activities magnify a sense of significance; yet, viewing those activities more holistically conveys a deeper perspective. This empathic outlook can alter perceptions; customers and users become more than clicks, downloads, and purchases. They are people trying to solve problems.

As leaders we need to be able to adapt our thinking appropriately. Approaching the same problems with the same toolset will never generate new results. Not only should we use different tools, but we must also employ different methods for finding, framing, and solving problems.

“Think outside the box” is a cliché that’s tossed around a lot. But what we really mean is that we want to disrupt business-as-usual. This ambition requires a different mode of thinking, and the best approach is cross-pollination.[38] We reach into cognitive toolboxes from other disciplines and apply their theories and frameworks to situations within our environment.[39]

As innovators, you need to be experimenters, designers, venture capitalists, product developers, and entrepreneurs always on the alert for growth and innovation. The way that we view ourselves is important, because it influences our behaviors. It shapes the way we think and feel about change and the future. It determines the types of questions that we ask and the paths we follow to answer them.

Problem discovery, as described here, isn’t a precise checklist of techniques; it’s an ethos and an attitude. By investing in other people’s problems, we can learn exactly what it is that they need to do, even if they don’t know what that is yet. By casting out our empathic radar, we can convert these insights into strategic initiatives.

The ability to learn, unlearn, and relearn is a vital attribute for the innovation seeker.[40] Taken further, the ability to conceptualize and then reconceptualize ideas based on feedback, usage, observations, corrected assumptions, or shifting priorities is another essential characteristic. We need to constantly recalibrate our thinking while things are in motion. We need to be okay with the prospect of not knowing everything and embracing the opportunity to figure out the next steps. We must always be looking for Plan B or Option C.

Our intention should never be to give people what they want, per se. Rather, through the art of problem discovery, we can design and develop the capacities, service models, and solutions necessary to deliver what people need, in order to accomplish the outcomes they desire.

Chapter 4 References

[1] Chapter 4 (Recognizing Needs and Opportunities is derivative of two works. 1) Entrepreneurship by Michael Laverty & Chris Littel, CC licensed by OpenStax; and 2) The Art of Problem Discovery by Brian Mathews (2013), CC-SA licensed by Virginia Tech.

[2] Lehrer, J. (2012). Imagine: How creativity works. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Liedtka, J., & Ogilvie, T. (2011). Designing for Growth. New York: Columbia University Press.

[3] Continuum. Swiffer: A Game Changing New Product. Retrieved from http://continuuminnovation.com/work/swiffer/

[4] Schoennauer, A. W. W. (1981). Problem Finding and Problem Solving. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. Runco, M. A. (1994). Problem Finding, Problem Solving, and Creativity. Norwood, N.J: Ablex.

[5] Christensen, C. M., Horn, M. B., & Johnson, C. W. (2008). Disrupting Class: How disruptive innovation will change the way the world learns. New York: McGraw-Hill.; Mathews, B. (2012). Think like a startup. Retrieved from http://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/18649 Neal, J. (March 2011). Prospects for Systemic Change across Academic Libraries. EDUCAUSE Review, 10-11.

[6] Dictionary – Merriam Webster. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com

[7] Getzels, J. W. (April 01, 1979). Problem Finding: a Theoretical Note. Cognitive Science, 3, 2, 167-172.

[8] Christensen, C. M., Cook, S., & Hall, T. (2005).; MARKETING MALPRACTICE. Harvard Business Review, 83(12), 74-83.

[9] Argyris, C. (May 01, 1991). Teaching Smart People How to Learn. Harvard Business Review, 69, 3, 99-109.; McGrath, R. G., & MacMillan, I. C. (2009). Discovery-Driven Growth: Boston: Harvard Business Press.

[10] Rodgers, P., & Milton, A. (2011). Product Design. London: Laurence King. Cagan, M. (2008). Inspired: How to create products customers love. Sunnyval, Calif: SVPG Press. Collins, M. (January 2010). Partnering for Innovation: Interviews with OCLC and Kuali OLE. Serials Review, 36, 2, 93-101.

[11] Oates, J. (Feb 18, 2011). Inventor of WorkMate dies. The Register. Retrieved from http://www.theregister.co.uk/2011/02/18/workmate_lotus/

[12] Runco, M. A. (1994). Problem Finding, Problem Solving, and Creativity. Norwood, N.J: Ablex.

[13] Ries, E. (2011). The Lean Startup. New York: Crown Business. Ries, E. Startup Lessons Learned. Blog: http://www.startuplessonslearned.com

[14] Easterly, W. (2006). The White Man’s Burden. New York: Penguin Press.

[15] Anstis, S. M. (1974). A chart demonstrating variations in acuity with retinal position. Vision Research. 14, 589-592. Kreider, T. (Aug 2, 2009). Averted Vision. New York Times. Retrieved from http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/02/averted-vision/

[16] Cross, N. (1982). Designerly Ways of Knowing. Design Studies. 3.4, 221-27. Seelig, T. (2013). Shift Your Lens: The Power of Re-Framing Problems. Rotman Magazine, 46-51.

[17] Checkland, P. (1981). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester: Wiley.

[18] Lockwood, T. (2010). Design Thinking: Integrating innovation, customer experience and brand value. New York: Allworth Press. Kelley, T., & Littman, J. (2001). The Art of Innovation. New York: Currency/Doubleday. Cross, N. (2011). Design Thinking: Understanding how designers think and work. Oxford: Berg. Bell, S. (January 2008). Design Thinking – a Design Approach to the Delivery of Outstanding Service Can Help Put the User Experience First. American Libraries, 44-49

[19] Martin, R. L. (2007). The Opposable Mind: How successful leaders win through integrative thinking. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

[20] Riel, J., & Martin, R. (2012). Integrative Thinking ,Three Ways: Creative Resolutions to Wicked Problems. Rotman Magazine, 4-9.

[21] Fisher, R., Ury, W., & Patton, B. (1991). Getting to Yes. New York, N.Y: Penguin Books.

[22] Martin, R & Austen, H. (1999). The Art of Integrative Thinking. Rotman Magazine, 2-4.

[23] De, B. E. (2010). Lateral Thinking. London: Viking. De, B. E. (1973). Lateral Thinking: Creativity step by step. New York: Harper & Row.

[24] Broza, G. (2012). The Human Side of Agile: How to help your team deliver. Toronto: Vantage Media. Cohen, D., Lindvall, M., & Costa, P. (January 01, 2004). An Introduction to Agile Methods. Advances in Computers, 62, 2-67.

[25] National Research Council (U.S.). (2011). Report of a workshop of pedagogical aspects of computational thinking. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press. Exploring Computational Thinking. Google in Education. Retrieved from http://www.google.com/edu/computational-thinking/what-is-ct.html Wing, J. M. (January 01, 2006). Computational Thinking. Communications- ACM, 49, 3, 33-35.

[26] Fritz, H. W. (2004). The Lewis and Clark Expedition. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press.

[27] Ginn, A. (Dec 8, 2012). Defining A Growth Hacker. Tech Crunch. Retrieved from http://techcrunch.com/2012/12/08/defining-a-growth-hacker-6-myths-about-growth-hackers/

[28] Kelley, T., & Littman, J. (2008). The Ten Faces of Innovation. London: Profile.

[29] McKinney, P. (2012). Beyond the Obvious. New York: Hyperion. Liedtka, J., & Ogilvie, T. (2011). Designing for growth. New York: Columbia University Press.

[30] Michalko, M. (2006). Thinkertoys: A handbook of creative-thinking techniques. Berkeley: Ten Speed.

[31] Marquardt, M. J. (2005). Leading with Questions: San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[32] De, B. E. (1985). Six Thinking Hats. Boston: Little, Brown.

[33] Foster, N. F., & Gibbons, S. (2007). Studying Students. Chicago: ACRL. Asher, A. & Miller, S. (2011) Ethnographic Research in Illinois Academic Libraries, Toolkit. Retrieved from http://www.erialproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Toolkit-3.22.11.pdf

[34] Bystedt, J., Lynn, S., Potts, D., & Fraley, G. (2003). Moderating to the max: A full-tilt guide to creative, insightful focus groups and depth interviews. Ithaca, NY: Paramount Market.

[35] Affinity Focus Group Exercise. Georgia Tech Libraries. Retrieved from http://librarycommons.gatech.edu/about/docs/affinity_exercise.pdf

[36] IDEO. (2011) Design Thinking for Educators, Toolkit, 2nd Edition. Retrieved from http://www.ideo.com/work/toolkit-for-educators

[37] White, F. (1987). The Overview Effect. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

[38] Johnson, S. (2010). Where Good Ideas Come From. New York: Riverhead Books.

[39] Here are some topics of potential interest: evolutionary ecology, lean manufacturing, emotional cartography, responsive design, user experience design, and visual merchandising.

[40] Toffler, A. (1970). Future Shock. New York: Random House.