13 Chapter 13: Pursuing Next Steps

Getting Ready to Launch Your Venture[1]

The big day has arrived. Your opportunity recognition process noted that your idea solves a significant problem or need, you double-checked that the target market is large enough for potential profitability, you have a method to reach this target market, you have a passion to start this company, and you found resources to support the start-up. Knowing that you analyzed and addressed these topics, you now need to consider some of the more sensitive topics regarding the agreements within your team. Many entrepreneurs overlook the issues discussed here or act on them in a generic manner instead of fitting them to the specific needs of the venture. This lack of due diligence can be detrimental to the success of the business. The advice presented here can help you avoid those same mistakes.

To protect the interests of all parties involved at launch, the team should develop several important documents, such as a founders’ agreement, nondisclosure and noncompete forms, and a code of conduct. Before these are drafted, the team should ensure the venture’s vision is agreed upon. The founding team needs to be in complete agreement on the vision of the venture before they can successfully create the founders’ agreement. If some team members have an interest in creating a lifestyle business, while other team members want to harvest the venture with significant returns, there is a clash between these expectations.

Important Founding Agreements

Honest and open discussions between the founding team (including your investor(s) if they are part of your initial funding) must take place before opening the venture. These frank discussions need to include a founders’ agreement as well as the identified vision for the venture. The founders’ agreement should describe how individual contributions are valued and fit into the compensation plan and should consider and answer these questions:

- Will the entrepreneurial team members receive a monthly compensation?

- Is there a vesting plan with defined timelines aligned with equity percentages?

- What happens if a team member decides to leave the venture before an exit event? How will that team member be compensated, if at all?

Discussing the entrepreneurial team members’ expectations avoids the problem of an entrepreneurial team member expecting a large equity stake in the company for a short-term commitment to the venture, and other misguided expectations. Such problems can be avoided by addressing the following questions:

- What activities and responsibilities are expected from each team member, and what is the process or action when individual overstep their authority?

- Is there an evaluation period during which the team members discuss each other’s performance? If so, how is that discussion managed, and is there a formal process?

- What happens if a team member fails to deliver on expected actions, or if an unexpected life event occurs?

The founders’ agreement should also outline contingency plans if the business does not continue. The following questions help define those next steps and need to be answered prior to opening the venture:

- If the venture is unsuccessful, how will the dissolution of the venture be conducted?

- What happens to the assets, and how are the liabilities paid?

- How is the decision made to liquidate the venture?

- What happens to the originally identified opportunity? Does a team member have access to that idea, but with a different team, or implemented using a different business model?

Once the venture opens, discussing these topics becomes more complicated because the entrepreneurial team is immersed in various start-up activities, and new information affects their thoughts on these issues. Along with these topics, the founders’ agreement should also state the legal form of ownership, division of ownership, as well as the buyback clause. The buyback clause addresses the situations in which a team member exits the venture prior to the next financing round or harvesting due to internal disputes with team members, illness, death, or other circumstances, clearly stating compensation and profit distribution (with consideration of what is reinvested into the venture). Discussing these topics provides agreement between all team members about how to address these types of situations. The buyback clause should also include a dispute resolution process with agreement on how the dispute solution is implemented. Identifying exactly how these items are handled within the founders’ agreement prevents future conflicts and even legal disputes.

After completing the founders’ agreement, you may want to have an attorney evaluate the documents. This checkpoint can identify gaps or decisions that were not stated clearly. After receiving the examined documents back, the team should once again review documents for agreement. If everyone is satisfied, each team member should sign the document and receive a copy. If, later, the team decides a change needs to be made to the founders’ agreement, an addendum can be created, again with all parties agreeing to any changes.

Your team may also want to consider two other formal documents: a nondisclosure agreement and a noncompete agreement. These documents can apply to not only the founding team but also other contributors. A nondisclosure agreement (NDA) prevents an individual from disclosing information about the venture. This document may include various topics, such as trade secrets, key accounts, or other information that is highly valuably to the venture and/or potentially useful to a competitor. A noncompete agreement prevents an individual from working for a competing organization while working for the venture, and generally for a period of time after leaving the venture – often one year, but it may be longer depending on the know-how or intellectual property of the exiting individual.

Taking Steps to Launch

The next action is outlining the operational steps in the venture creation process. A good approach is to create a chart that identifies how you should proceed. The goal in creating this chart is to recognize what actions need to be taken first. For example, if you need a convection oven for your business, what is the timeline between ordering and receiving the oven? If you need ten employees to manually prepare and package your product, how long will it take to interview and hire each person? According to Glassdoor, the hiring process took 23 days in 2014 and appears to be lengthening in time as organizations become more aware of the importance of hiring the right person.[2] What about training? Will your employees need training on your product or processes before starting the venture? These necessary outcomes need to be identified and then tracked backwards from the desired start date to include the preparatory actions that support the success of the business. You’ve probably heard the phrase that timing is everything. Not only do entrepreneurs need to be concerned about finding the right time to start the venture, they also need the right timing to orchestrate the start-up of the venture.

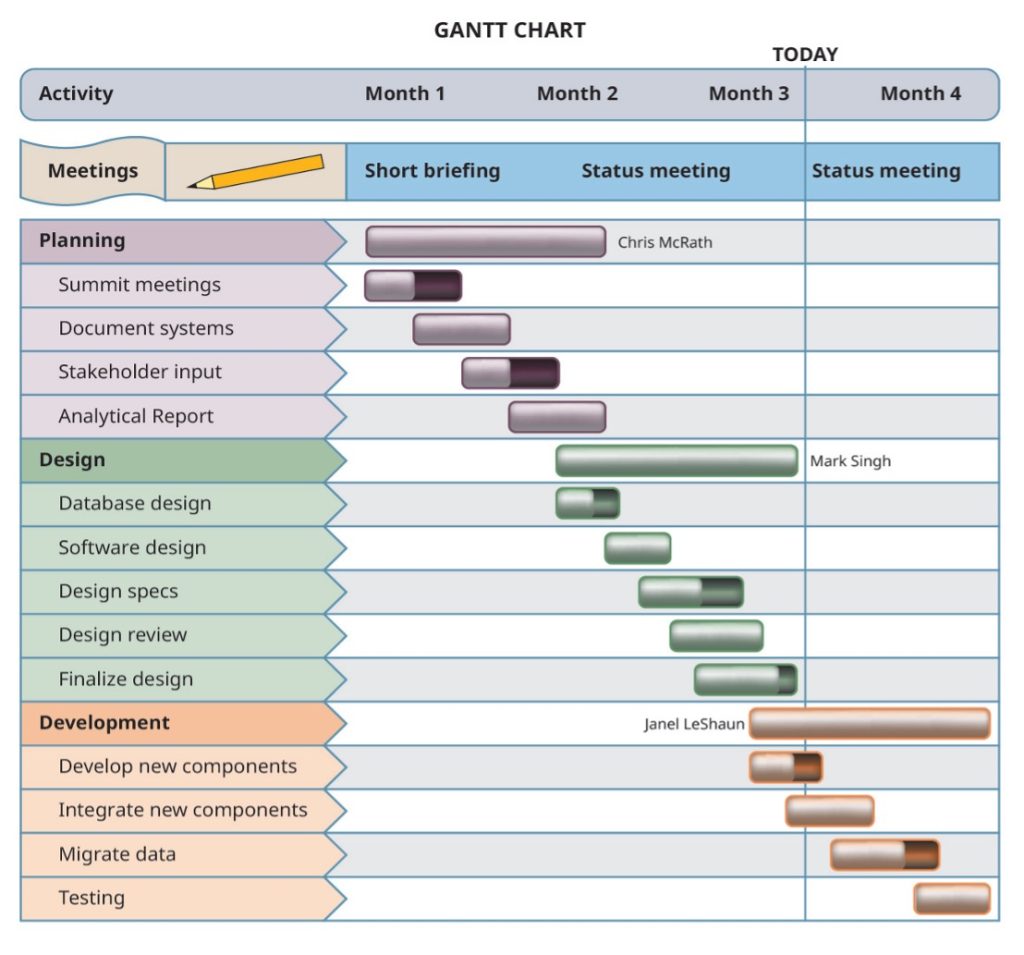

You might want to reach out to other sources to find examples of how other entrepreneurs worked through their operational start-up steps. One example is a Gantt chart, which is a method of tracking a list of tasks or activities aligned with time intervals. You can use this tool to help identify and schedule the operational steps that need to be completed to launch the venture. One approach to creating a Gantt chart is for each team member to independently create a list of operational activities or tasks required to start the venture that fall under their area of involvement. Then the team can create a master list of activities to discuss: This helps clarify who is contributing to or owning each task. Next, have all team members create their own Gantt chart based on their task list: That is, the time required for each task should be spelled out, including steps that must happen sequentially (when one task cannot be started until another step is complete). Once again, bring your team together to create one master Gantt chart (see Figure 13.1 below for an example). This helps to ensure that dependencies from one member to another are accounted for in the planning. These contingencies and dependencies need to be identified and accommodated for in a master schedule. After completing the chart, agree on assignments of responsibility to follow through on the activities, based on the timelines from the Gantt chart.

Figure 13.1 Sample Gantt Chart

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license

Launch Considerations

Sage advice in launching the new venture is to quickly recognize when you don’t have the answer or information to make the best decisions. In the early stage of launching the venture, the level of uncertainty is high, as is the need for agility and spontaneity. Even identifying the actual moment when the venture becomes a new venture can be difficult to determine. Should the venture be recognized as a new venture after receiving the necessary licenses or tax identification number, or when the first sale occurs, or when funds are first invested, or by some other method?

It is also important to keep in mind the end goal of the venture. For example, many highly successful ventures never earn a dollar in sales. Depending on the entrepreneurial team’s vision and the business model selected, the venture could be highly valuable from a harvest, or sale of the venture, perspective. Because of this pattern, entrepreneurs are often advised to “begin with the end in mind” when launching a new venture. If the goal is to sell the venture to another company, we may want to identify that company before launching the venture. Of course, at this point, this is only a desire or hope, as you cannot require or expect another company to have an interest in your new venture. But you can design the new venture to align with this end goal by making decisions that support this end goal. Consider the example of YouTube, a startup with zero dollars in sales but with a harvest price of $1.65 billion in stock from Google. The startup team, former PayPal colleagues, understood that the technology was being developed for video searching and recognized that creating a platform to house video-sharing would be desired by companies such as Google at some point in the future. Consider the tight timeline between 2005 when YouTube began supporting video sharing, and the harvest of YouTube to Google in 2006, 21 months later. This example clearly points to the importance of beginning with the end in mind.

Launching your venture is a unique experience for every team and for every venture. These novel situations and uncertainties create both challenges and new learning opportunities. Accepting that a multitude of possibilities exists and recognizing the importance of researching and discussing actions are valuable to the success of the team. Conducting research to explore decisions will improve your venture’s success. Although these decisions might seem difficult, the next section addresses how to approach difficult decisions.

Planning Ahead for Challenges[3]

Now that you are prepared to launch your business venture, let’s look at your business plan and the assumptions you made while preparing it. Did you keep a list of assumptions? Did you update assumptions as new data and information suggested “retiring” some initial ideas? Did you identify key milestone and timelines? Did you fully assess risks and have mitigation plans to address them? These are essential questions to consider before launch. As the business venture comes into existence, you should review your assumptions and identified milestones. Ask the following questions:

- Are your assumptions still realistic?

- Is your business venture on track for the associated milestones?

- Do you need to consider any changes that have occurred in the industry you plan to enter? Has the competition changed? Are there new regulations?

Tracking changes and comparing them to your earlier assumptions provides an opportunity to reconsider necessary changes to your plan. After you begin your venture, you should continue to review your assumptions and milestones. If you are not meeting your projections, what has changed? What decisions should you adjust to situate your venture into a stronger position for success? If your venture is doing better than expected, analyze why the venture is exceeding your forecasted projections.

It is important to return to your plan and consider what you will do if your assumptions are incorrect, so if your milestones aren’t met, you can avoid the problem of escalation of commitment. The concept of escalation of commitment describes when an entrepreneur feels so committed to the plan of action that they end up losing their perspective on the reality of what is happening to the venture. They ignore the danger signs and think that if they just work harder, or pour more money into the venture, they can force the venture to become successful. Once an entrepreneur becomes this committed to the venture and is working passionately to keep the enterprise afloat, they can lose the focus and objectivity to make rational decisions. They can begin to react to the situation, stubbornly persist, or begin to ignore the danger signs that should alert them that reevaluation of the situation is necessary. As such, escalation of commitment prevents the recognition that a pivot (or exit) is necessary.

To avoid failure to pivot or to exit a venture, an entrepreneur can identify fail-safe points to trigger consideration of what actions are needed to bring the venture back to a healthy position and whether this action is reasonable and feasible. Identifying these trigger points and creating contingency plans before opening the venture can prevent the entrepreneur from becoming trapped by the dangers of becoming overly committed and throwing resources into an impossible situation.

Anticipating Growth Challenges

Before starting the venture, the start-up team should ask these two questions:

- What happens if we are wildly successful?

- What happens if we are horribly unsuccessful?

The purpose of these questions is to consider how resources and debts will be resolved before the venture begins to use or acquire resources. If your relative or friend contributed by letting you use her living room for your planning meetings and bought pizza to keep the team energized, does she have a stake in your venture? If your venture is wildly successful, she might believe that she should receive financial remuneration for her contributions. The point is, people often change when there is a lot of money on the table or when the venture is on the edge of disaster. Planning for both extremes provides a framework for the entrepreneurial team to consider their own expectations and the expectations of other people involved in the project before these types of situations happen.

This discussion should also address the agreed-upon method for making difficult personnel decisions. Is there a severance package? If so, who is entitled to the severance package? Does the exit of employees, and even people on the start-up team, exclude them from future expectations if the venture is successful? If the funding source includes contractual liabilities, how is the release of a start-up team member resolved? If new team members or employees are added, will these people be considered employees who earn wages, or are some positions identified as receiving equity positions with financial gains through the harvesting of the venture? Addressing these questions before starting the venture can preserve relationships by clearly stating and agreeing to these sensitive decisions that can carry long-term consequences. In considering these questions and awareness of how the venture’s need will change in the future, you might want to revise your founder’s agreement for clarity and alignment with any new information or concerns that arise.

Business Structures: An Overview of Key Considerations[4]

One of the most important initial decisions that an entrepreneur must make, from a legal perspective, is the legal organization of a business, called the business structure or entity selection. The structure of a new business creates the legal, tax, and operational environment in which the business will function. To select an entity, entrepreneurs need to have a clear understanding of the type of business they seek to establish, the purpose of the business, the location of the business, and how the business plans on operating.

The choices of business structure are varied, with several basic entities, each with several variations. Many ventures, regardless of humble beginnings, may have the potential to evolve into significantly larger business ventures. This is what makes the initial decision so important. Founders should think through every step of business development, beyond the inception or formation, and consider possible paths of the business. How an entrepreneur organizes the business, or which business structure they choose, will have a significant impact on both the entrepreneur and the business.

For-Profit vs. Not-for-Profit Businesses

Owners form businesses for one of two purposes: to make a profit or to further a social cause without taking a profit. In either case, there are multiple options in terms of how a business is structured. Each structure carries its own tax consequences determined by the owners’ financial requirements and how the owners want to distribute profits. The structure, in turn, determines the appropriate income tax return form to file.

Characteristics of Not-for-Profit Organizations

A not-for-profit organization (NFPO) is usually dedicated to serving the public interest, furthering a particular social cause, or advocating for a common shared interest. They must follow specific regulations regarding eligibility, government lobbying, and tax-deductible contributions. In financial terms, a not-for-profit organization uses its surplus revenues to achieve its ultimate objective, rather than distributing its income to the organization’s shareholders, partners, or members. Common examples of NFPOs include educational organizations such as schools, colleges, and universities; public charities such as the United Way; religious organizations such as places of worship; foundations; trade organizations; and issue-advocacy groups. Other organizations considered NFPOs include nongovernmental organizations, civil society organizations, foundations that provide funding for various activities, and private voluntary organizations.[5]

Because they are typically created for the common good, NFPOs are usually tax-exempt as categorized by the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This means that they do not pay income tax on the money that they receive. These types of organizations are created under state law, but also subject to federal and local laws.

To operate as a not-for-profit business, most states require that the entrepreneur create a corporation that has the specific purpose of acting in the public interest. This type of corporation does not have owners but has directors charged with running the organization for the public good, subject to bylaws. Some states only require a minimum of one director, whereas other states may require three or more directors. This is an important consideration for an entrepreneur, because the nonprofit corporation will need the approval of all the directors, and not just one person for its creation. Careful vetting of directors is the best policy of any entrepreneur, since directors have a duty to the corporation.

Because state laws vary, a not-for-profit corporation created for the common good in one state needs permission from another state to operate in that state. The permission is typically an approval from the other state’s secretary of state memorialized in the form of official documents or permits. When operating in different states, the entrepreneur needs to make sure that the business follows all laws, rules, and regulations for each state.

Characteristics of For-Profit Businesses

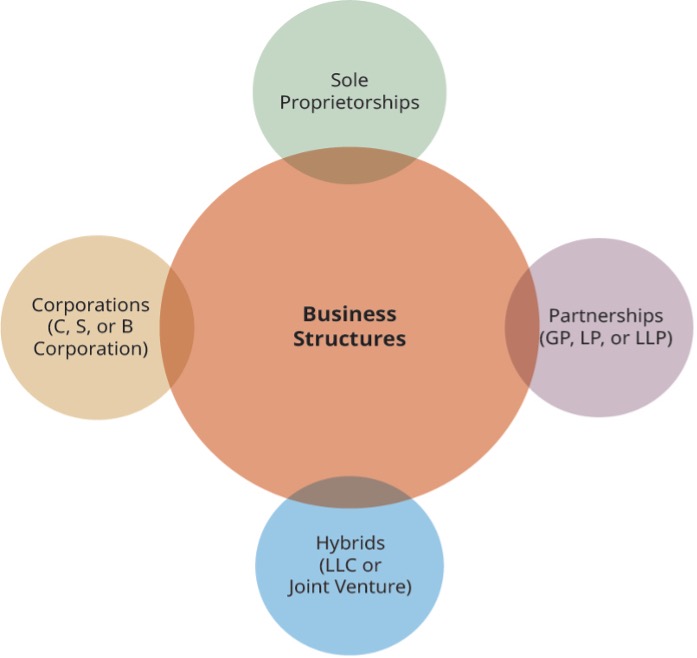

A for-profit business is designed to create profits that are distributed to the owners. For-profit businesses are commercial entities that generally earn revenue through the sales of products or services. There are multiple entity structures for for-profit business entities (see Figure 13.2 below), including sole proprietorships, corporations, and partnerships, as well as hybrid entities such as limited liability companies (LLCs) and limited liability partnerships (LLPs). Each structure carries specific set-up requirements, different obligations to fulfill (e.g., taxes, government filings), and varying ownership risks and protections. Entrepreneurs should consider these factors as well as the expected business growth when selecting a structure, while being aware that the structure can and should change as the venture grows.

There are a few particularly important considerations to keep in mind. The first is whether the entity is being created to produce a profit for its owners or shareholders, or whether it will be structured as a not-for-profit entity. A second factor is the state of incorporation, as state law defines each business’s creation, with different states permitting different types of entities and various legal protections. Other considerations include how the structure facilitates bringing in new investors, allows the owners to transfer profits out of the business, and supports a potential subsequent sale of the entity. Taxation is also a crucial aspect of business success, and the business structure or entity directly affects how it is taxed.

Figure 13.2 Basic Business Structures

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license

For example, if you want to share authority, responsibilities, and obligations with other people, your best choice may be a partnership, in which other people contribute money and help manage the business. Alternatively, if you prefer to manage the business yourself, a better choice might be a single-member LLC, assuming you can borrow money from a lender if needed. Conversely, if you believe your idea is so popular that you may grow rapidly and want the ability to raise capital by selling interests in your business through equity or debt, then a corporation may be a better choice.

Ultimately, the entrepreneur must first select the type of entity to be created (alternatives discussed further below). Then, depending on the entity chosen, they must file the appropriate paperwork with the office of the secretary of state where the entity is formed. You may also seek to obtain legal and tax advice about your structure.

Corporations

A corporation is a complex business structure created when the original incorporators (i.e., owners) file a formal document called the articles of incorporation, or other similar documentation, with a state agency, often the secretary of state’s office or the state division of corporations. Corporations operate as a separate legal entity apart from the owners. The owners are called shareholders and can be individuals, other domestic or foreign corporations, LLCs, partnerships, and other legal entities. Corporations may be for-profit or not-for-profit, as discussed previously.

Incorporating a company means that the corporation operates as an entity that has some of the same rights as an individual. For example, individuals and corporations can sue and be sued, and corporations have the rights to own property, to enter and enforce contracts, to make charitable and political donations, to borrow and lend money, and to operate a business as if the corporation were an individual. Most states require a corporation to be registered in that state in order to conduct business operations and to enter into and defend lawsuits in that state, especially if the business was incorporated in a different state. Registration is not the same as forming the initial corporation; it is simply the process of filing informational documents by entities that have already been incorporated in another state. States also tax the operations or sales a corporation makes in the state in which it has certain operations.

Corporations are the only type of entity that the law allows to sell shares of stock. No other entity (e.g., LLC, partnership) may do so. Those individuals or other entities that buy stock become shareholders and own the corporation. Some corporations have millions of shareholders, and others have as few as one. State incorporation laws vary: Some require at least three shareholders, but others allow a one-owner business to incorporate. Thus, an entrepreneur may start a company as the sole owner of the company and later incorporate and sell shares of stock or bonds to other investors in the company.

Corporations sell, or issue, stock to raise capital, or money, to operate their businesses. The holder of a share of stock (a shareholder) purchases a piece of the corporation and has a claim to a part of its assets and earnings. In other words, a shareholder is now an owner of the corporation. Thus, a share of stock (also called equity) is a type of security that signifies proportionate ownership in the issuing corporation. Stocks are bought and sold predominantly on stock exchanges, although there can also be a private sale between a seller and a buyer. These transactions must conform to a very complex set of laws and government regulations, which are meant to protect investors.

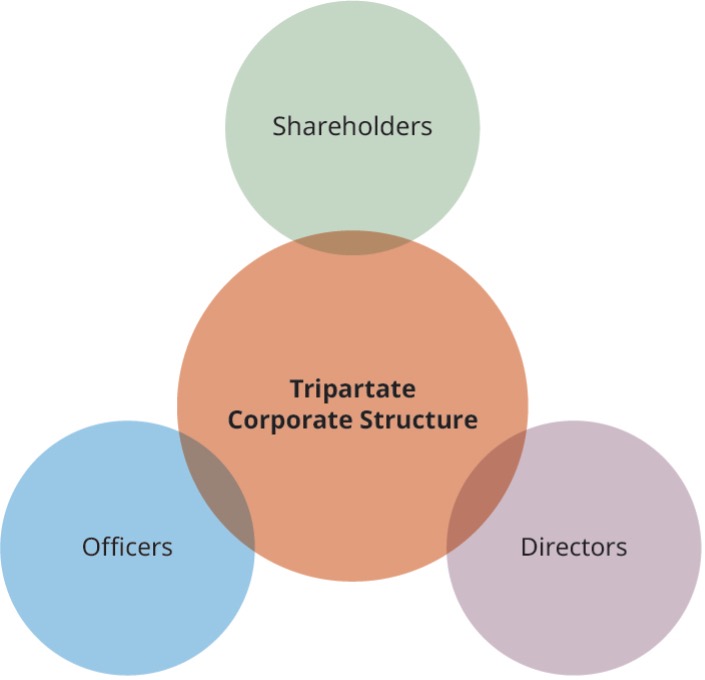

Most corporations use a three-part (tripartite) approach to ownership and management (see Figure 13.3). After the corporation is created, the shareholders typically elect a board of directors. The board, which has oversight responsibilities for the operations of the company, then appoints officers, who are responsible for the corporation’s day-to-day operations.

Figure 13.3 Tripartite Approach to Corporation Management

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license

Advantages and Disadvantages of Corporations

Use of a corporation allows the entrepreneur to shield themselves, and other owners, from personal liability for most legal and financial obligations. The benefit of limited liability is one of the primary reasons entrepreneurs incorporate. However, the administration of a corporation requires more formality than other types of entities, such as sole proprietorships and partnerships. A corporation must follow the rules for such entities. The requirements include maintaining bylaws, holding annual shareholder and director meetings, keeping minutes of shareholder and director major decisions, ensuring that officers and directors sign documents in the name of the corporation, and importantly, maintain separate bank accounts from their owners and keep detailed financial and corporate records. A failure to follow the rules could lead to the loss of limited liability, known as “piercing the corporate veil.”

C Corporations, S Corporations, and Benefit Corporations

The categorization of corporations as either C corporations or S corporations is largely a tax distinction. An S corporation is a “pass-through” entity, where shareholders report and claim the business’s profits as their own and pay personal income taxes on it. Alternatively, the government taxes a C corporation at the corporate level, and then levies taxes again on the owners’ personal income tax returns if corporate income is distributed to the shareholders as dividends.

Conversely, the distinction between Benefit corporations and C or S corporations is not one based on taxes at all, but rather on purpose and approach. A Benefit corporation is a business that embraces a commitment to social and environmental performance, public transparency, and accountability to balance profit with social purpose. They may be taxed as C corporations or S corporations. Although benefit corporations are a newer form of for-profit corporation, 40+ states have already proposed or passed legislation acknowledging this type of legal entity. The benefit corporation’s objective is directed toward maximization of benefits for all stakeholders, meaning that it does not only maximize stockholder profits. Maximization of stakeholder benefits is directed through the corporate charter of a benefit corporation. The state of incorporation directs how benefit corporations are created, but generally, this model expands the “perspective of traditional corporate law by incorporating concepts of purpose, accountability, and transparency with respect to all corporate stakeholders, not just stockholders.”[6] This means that the use of this type of business structure needs to be carefully considered by the entrepreneur , because the responsibility of the business will include consideration of the stakeholders outlined in the corporate charter, not just the profit maximization for the shareholders.

A benefit corporation may or may not also be a B corporation (also known as B Corps). While B corporations and benefit corporations share some common goals, B corporations are not a specific legal entity. Instead, becoming a B corporation requires going through a certification process that involves complying with various standards and undergoing a regular audit of this compliance (similar to Fair Trade or Organic certification).[7] As of 2019, there are approximately 3,000 certified B corporations in sixty-five countries, covering 150 different industries.[8] The B corporation certification acts as a seal of approval for businesses voluntarily trying to be socially and environmentally responsible (see Figure 13.4 below).

Figure 13.4 B Corps Certification Logo

Credit: modification of “Runa B Corp Label” by “Lelepanne”/Wikimedia Commons, CC0

Overview of Corporate Taxation

All for-profit corporations are subject to income tax at the federal level, and usually at the state level as well. Regardless of tax elections, both C- and S corporations are subject to taxation. Tax planning is a major issue for most corporations and may explain some key decisions, such as where they are located. That could involve decisions about which state the corporate headquarters are in, or even in which nation the headquarters are located. This is because tax laws may vary significantly by both state and nation. Many states add a state-level income tax, ranging from 2-12% – while some states (e.g., Texas) do not have a corporate income tax, in an effort to attract corporations to the state.[9]

Taxation of C Corporations

C corporations pay corporate income taxes on profits made. Individual shareholders are also subject to personal income taxes on any dividends they receive. Most attorneys and accountants refer to this concept as the double taxation disadvantage. However, the historical tax disadvantage has been recently reduced because of the decrease in the income tax rate paid by C corporations by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.[10] This decrease, in turn, reduces the double tax disadvantage. Further, the ability to retain and reinvest profits in the company at a lower corporate tax rate is an advantage.

A C corporation does come with a degree of added formality, or as some may refer to it, red tape. According to most states’ corporation laws, as well as federal tax and securities laws, the corporation must have company bylaws and must file annual reports, financial disclosure reports, and financial statements. They must hold at least one meeting each year for shareholders and directors where minutes are taken and maintained to display transparency. A C corporation must also keep voting records of the company’s directors and a list of the owners’ names and ownership percentages.

Despite the tax implications, the C corporation structure is the only one that makes sense for most large U.S. businesses, because it allows for the wide-scale sale of a large amount of stock to the general investing public without limits. A C corporation can have an unlimited number of shareholders that are individuals or other business entities and are either U.S. citizens or foreign nationals.

Taxation of S Corporations

As previously discussed, the S corporation is a corporate entity in which the firm’s profit is passed through its stockholders (shareholders), usually in proportion to their investment. This is known as pass-through taxation. Essentially, this amounts to tax management by the corporate owners. The IRS taxes the corporate profits at the personal income tax rates of the individual shareholders.

S corporations (S stands for “small”), also called subchapter S corporations, must comply with several important restrictions with which entrepreneurs must comply. S corporations have a limit on shareholders. Unlike with C corporations, the Internal Revenue Code limits the number of S corporation shareholders to 100 or fewer, and owners can only be individuals, (or estates and certain types of tax-exempt entities). Additionally, the individual shareholders must also be US citizens or legal permanent residents. Furthermore, S corporations may only have one class of stock, whereas C corporations may have multiple classes. For example, in a C corporation, there might be voting shares, nonvoting shares, common shares (the type most people buy), and preferred shares (which are repaid first in the event of bankruptcy).

Partnerships

A partnership is a business entity formed by two or more individuals (partners), each of whom contributes something (e.g., capital, equipment, skills). The partners then share profits and losses. A partnership can contract in its own name, take title to assets, and sue or be sued. Partnerships can take many forms – such as general partnerships (GPs), limited partnerships (LPs), limited liability partnerships (LLPs), and, in some states, limited liability limited partnerships (LLLPs). Each of these will be discussed further below.

All states require the registration of any limited liability entity. State law, which governs the formation and operation of all partnerships, can vary from one state to another. This section contains some generalizations that may vary according to jurisdiction. Federal law has very limited applicability to partnerships, primarily in the area of federal income taxation.

A partnership generally operates under the terms of a written partnership agreement, but there is no requirement that the agreement be in writing. In many instances, the only requirement is that two or more parties come together to operate a business for profit. Entrepreneurs need to be careful because a general partnership can be informally created by the actions of two or more people or entities pursuing a business for profit while sharing management duties. State courts may deem these actions the creation of an informal or even formal partnership.

For this reason, if two entities or people come together to purse a joint business operation or strategy, the parties should document the pursuit of the business venture in a written agreement. Many state laws require that some forms of a partnership use a formal written partnership agreement or articles of partnership. Regardless, the entrepreneur needs to have a clear understanding of the exact business relationship before embarking on a new venture, and a partnership agreement can and should outline those details. A partnership agreement addresses many important topics, including the monetary investment of each partner, their management duties and other obligations, how profits or losses are to be shared, and all the other rights and duties of the partners.

The general partnership (GP) is a very common business structure in the U.S. It is created when two or more individuals or entities come together to create, own, and manage a business for profit. A GP is not technically required to have a written agreement, or to file or register with the state government – however, GPs should have their business structures described in writing, so that entities working together understand the business and the business relationship. In GPs, the liability of the owners is considered “joint and several,” meaning that not only is the partnership entity liable, so too is each general partner.

The liability of partners may be limited by the creation of an LP. A limited partnership (LP) requires at least one general partner and one or more limited partners. A limited partner’s liability is typically capped at their investment, unless they take on the duties of a general partner. The general partner is personally liable for all the operations of the LP. LPs have been around for many years and allow investors to provide funding for a business, while limiting their investment and personal risk. LPs are commonly used in businesses that require investment capital but do not require management participation by LP investors. Examples include buying commercial real estate, making and funding movies or Broadway plays, and drilling oil and gas wells.

Some states have relatively recently started to allow variations on the LP structure and offer businesses the option of forming a related type of partnership entity. In limited liability partnerships (LLPs), partners are licensed professionals, with limited liability for financial obligations related to contracts or torts, but full liability for their own personal malpractice. The primary difference between LLCs and LLPs is that LLPs must have at least one managing partner who bears liability for the partnership’s actions. An LLP’s legal liability is the same as that of an owner in a simple partnership. Entities that are formed with a founding partner (or partners) often structure as an LLP – examples include law firms, accounting firms, and medical practices. In this situation, junior partners typically make decisions around their personal practice but don’t have a legal voice in the direction of the firm. Managing partners may own a larger share of the partnership than junior partners.

The final type of partnership is a limited liability limited partnership (LLLP), which allows the general partner in an LP to limit their liability. In other words, an LLLP has limited liability protection for everyone, including the general partner who manages the business.

Advantages and Disadvantages of General Partnerships

When a GP is created, one partner is liable for the other partner’s debts made on behalf of the partnership, and each partner has unlimited liability for the partnership’s debt. This creates a problem when one partner disagrees with the source or use of funds by another partner in terms of capital outlay or expenses. Each partner in a GP can manage the partnership. If something negative happens, such as an accident (called a tort) that injures people and produces liability (e.g., a chemical spill, auto accident, or contractual breach), each of the partners is personally liable, with all their personal assets at risk. Also, the partners are liable for the taxes on the partnership, as a GP is a pass-through entity, where the partners are taxed directly, but not at the partnership level.

The popularity of GPs has been on the decline, and the use of LPs, LLPs, and LLLPs has expanded. Due to the different risks associated with them, GPs are often not the best choice of business entity. Other types of entities offer the protection of limited liability and are thus better choices in most circumstances. However, GPs may be a useful structure in certain situations, because they are relatively easy and inexpensive to form. as. As long as the business does not have a high likelihood of liability-producing accidents or situations, a GP can work. Consider, for example, partners offering graphic design or photography services.

Taxation of Partnerships

All partnerships are considered pass-through entities – so the partnership’s profits are not taxed at the entity level, as with a C corporation. Rather, profits are passed through to the partners, who claim the income on their own tax returns. Partners pay income taxes on their share of distributed partnership profits. Thus, there is no such thing as a partnership tax rate.

Limited Liability Companies

In 1977, Wyoming was the first state to allow the limited liability company (LLC) format. In contrast, corporations have been around since the early nineteenth century. However, LLCs now significantly outnumber corporations, with some estimates indicating that four times as many LLCs are formed as corporations[11]. An LLC is a hybrid of a corporation and a partnership that limits the owner’s liability. The big advantage that LLCs have over GPs is in the protection of owners from personal liability. Thus, an LLC is similar to a corporation in that it offers owners limited liability.

The owners of an LLC are called members. The owner (if a single-member LLC) or owners often run the company themselves. These are called member-managed LLCs. The daily operations of the LLC can also be delegated to a professional manager, which is called a manager-managed LLC. If the original organizer of the LLC chooses, they can organize an LLC in which the owners (members) will have little or no management responsibility because it has been delegated to a professional manager. These options when drafting an LLC’s operating agreement allow an LLC to operate in different ways, so that an entrepreneur can develop a business structure best suited to the needs of the business.

Advantages and Disadvantages of LLCs

The advantage that LLCs have in comparison to corporations, especially for entrepreneurs, is that they are easier to form and less cumbersome to operate because there are fewer regulations and laws governing LLC operations. Although LLCs tend to be easier to create, they still require a filing of articles of formation with the state and the creation of an operating agreement. LLC owners can be individuals or other business entities. The entrepreneur can use the flexibility of an LLC to create a business structure suitable to the operational and tax needs of the business. That said, when evaluating the use of an LLC as the structure for your business, it is important to know that there are some constraints on the use of an LLC. Each state may permit varying types of LLCs, with different types of formation agreements and operating agreements. In most states, a nonprofit business cannot be an LLC. Additionally, most states do not permit banks or insurance companies to operate as LLCs.

As long as members (owners) do not use the LLC as an alter ego and/or commingle personal funds with LLC funds, the LLC provides the corporate shield of limited liability to the investors. If the LLC is operated to protect a sole proprietor, this might become an issue if the sole proprietor commingles funds. Commingling funds or assets gives rise to the sole proprietor or other members of a multi-owner LLC being liable for all the debts of the LLC. Generally, the ownership of an LLC is represented by percentages or units. The term shares is not used in operating agreements, because LLCs cannot sell shares of stock like a corporation can; thus, owners are not technically shareholders.

Taxation of LLCs

Entrepreneurs have options regarding the taxation of LLCs. The default taxation for a multi-owner LLC is as a partnership, meaning profits pass through and get taxed on the owner’s federal tax return. However, they can elect to be taxed as a corporation instead. Similarly, single-member LLCs can be taxed as a sole proprietorship or a corporation. The fact that an LLC can select its method of taxation as either a C corporation, S corporation, or partnership allows the entrepreneur flexibility in creating the business structure of their choosing.

However, tax laws change. For example, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 may make formation as an S corporation more attractive to some entrepreneurs than formation as an LLC, at least as far as taxation is concerned. You should seek advice from a tax accountant to ensure that you are able to make decisions based on the most current regulations.

Sole Proprietorships

A sole proprietorship is a business entity that is owned and managed by one individual and has very little formal structure and no mandatory filing/registration with the state. This type of business is very popular because it is easy and inexpensive to form. The owner, called a sole proprietor, is synonymous with the business and is therefore personally liable for all debts of the business. Sole proprietors do not pay separate income tax on the company, instead reporting all losses and profits on their individual tax returns.

According to the Tax Foundation, there are more than 23 million sole proprietorships in the US, far more than any other type of business entity.[12] This statistic means that the sole proprietorship is by far the most common business structure, even though the business is not legally separate from its owner. The primary reason that many entrepreneurs choose the sole proprietorship format is that they do not have to make a choice, get professional advice, or spend any money. An entrepreneur who just starts doing business is automatically a sole proprietorship unless they elect to become a different type of entity and file that paperwork. An entrepreneur who becomes a sole proprietor does not necessarily have to go to an attorney or an accountant, or file any documents, making a sole proprietorship quick, easy, and cheap to form and operate.

Another development related to the decision to be a sole proprietor is the rapid growth of the gig economy. Some individuals prefer to work on their own rather than become a full-time employee. Being a gig worker falls somewhere between being a business owner and being an employee, so many gig workers, ranging from drivers for a ride-sharing company to instructional designers, operate as de facto contractors who are sole proprietors. However, there remains a debate about whether these gig workers should be deemed sole proprietors. Recently, California passed a new law that extends wage and benefit protections to many thousands of workers who were previously self-employed sole proprietors working in the gig economy. The new law is based on the presumption that when workers are misclassified as independent contractors rather than as employees, they lose basic benefits such as a minimum wage, paid sick days, and health insurance.

The sole proprietorship is the simplest method to operate a business (often under the owner’s name), and the owner is typically taxed directly by the IRS by attaching a Schedule C (Profit or Loss) form to the owner’s individual tax return. To document one’s income, instead of having a Form W-2 from one’s employer, many self-employed individuals receive one or more 1099-MISC (Miscellaneous Income) forms from clients, which typically show that the taxpayer is operating a sole proprietorship. Sole proprietors are allowed to deduct their business expenses related to their income and, as both employer and employee, are required to pay the full amount of employment taxes for Social Security and Medicare.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Sole Proprietorships

The sole proprietorship is the easiest business to start. However, there is almost no differentiation from the individual starting the business. A sole proprietor is the investor, owner, and manager of the business enterprise. They are personally liable for everything – including all taxes and any unpaid debts of the business venture. The sole proprietor also has no business to sell and can sell only assets related to the business.

Taxation of Sole Proprietorships

A sole proprietorship is not taxed as an entity. All profits pass through to the owner, who pays individual income taxes on all profits earned. It does not matter whether the owner takes money out of the business or leaves it in the business; all profits are taxed to the individual owner. This requires significant planning and may be a potential disadvantage, depending on how the individual owner’s personal tax rate compares to the corporate rate.

Considering the Impact of Capital Acquisition and Business Domicile

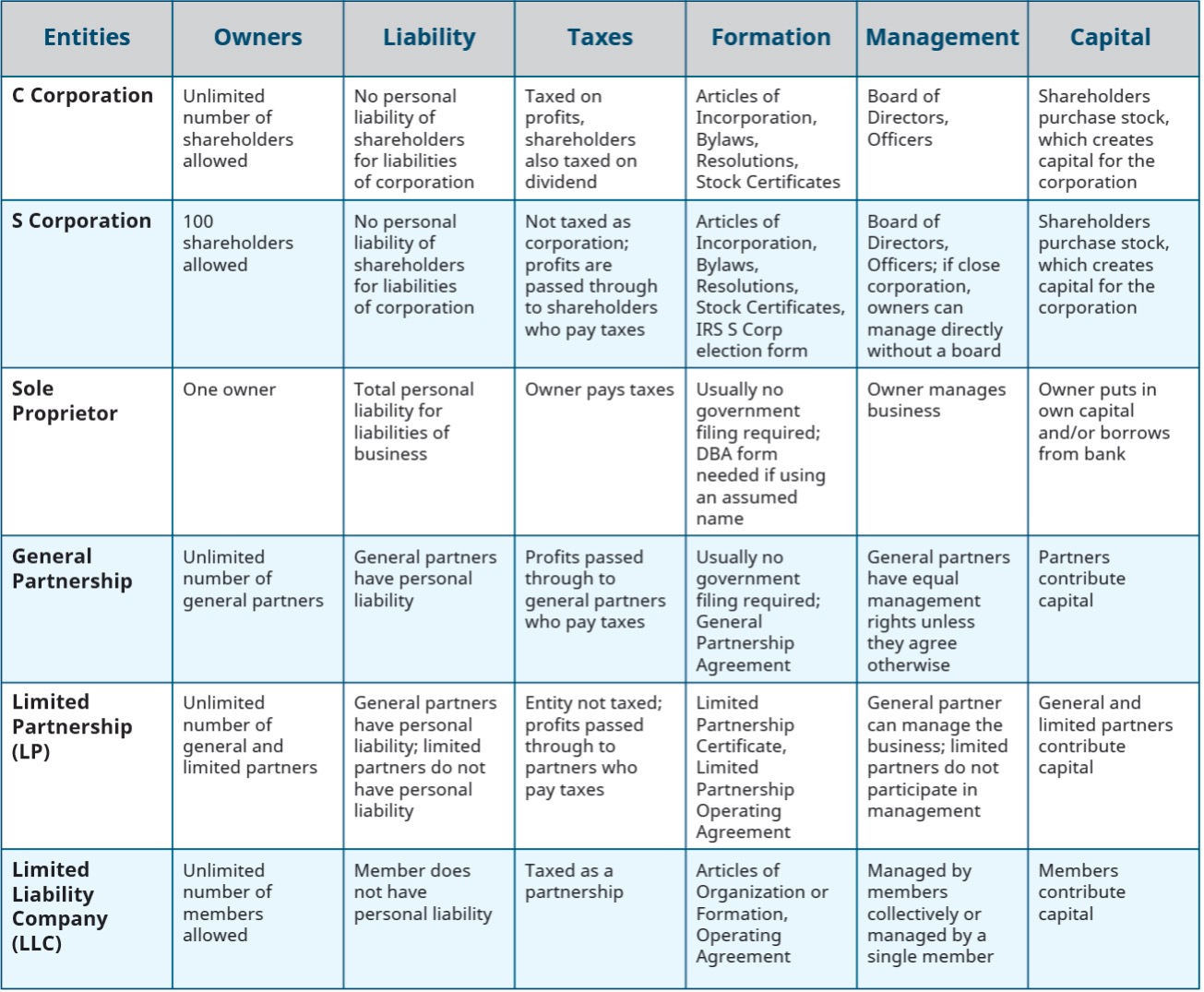

Figure 13.5 below summarizes the business structure characteristics discussed above. In addition to ownership structure and taxation, there are several other factors that entrepreneurs might consider when selecting an entity. For example, when choosing a business structure, a founder may be interested in how to raise capital to use in the business. Another issue to consider includes where to form a new business, since formation is largely a state issue, and there are fifty different states from which to choose. This has the potential to affect multiple aspects of one’s business, including income and sales tax issues, government regulation, and litigation location.

Figure 13.5 Characteristics of Different Business Structures

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license

Capital Acquisition Considerations

Once an entrepreneur has created a business plan, the next requirement is to capitalize the business venture. If the entrepreneur wants to start out small, a sole proprietorship is all that is needed, although even for small businesses, this structure carries a high degree of risk. Basically, the entrepreneur can simply start working on the business venture. If the entrepreneur’s business venture is larger, raising capital becomes a major issue. This can be done though bank loans or investors.

Entrepreneurs may eventually need capital to grow their business, which typically comes in the form of cash. Entrepreneurs must consider the business structure they select for raising cash in the future if they plan to grow their business. Banks, family members, friends, or others can lend cash to an entrepreneur, but these loans may not give the lenders ownership rights in the company. The lenders may take a lien on the assets of the business venture but do not necessarily have the right to run the business. Management is typically left to the owners when borrowing funds, but when a company receives investment funds, the investor also receives an equity share in the business and may be involved in management.

Owners and investors may want to have the right to operate the business or may want the investment structured in such a fashion so that the investors only participate in the profits or losses of the business, but do not operate the business. Depending upon the type of the business and the expectations of the entrepreneur and possible owners, this needs to be considered before creating a company. An entrepreneur raising capital needs to consider what participation is desired from investors and the timing of the needed capital. The issues that investors tend to look at include transferability or sale of their ownership interest, ability to raise additional capital, and protection of the investors’ assets outside of the investment. Remember, investors become owners, whereas lenders are not owners. If the entrepreneur does not seek investment from outsiders, these considerations are not as important.

Agreements describing how the owners share in profits and losses, and how the owners share in making decisions about the business venture can and do change. Many owners and entrepreneurs desire that their company become a publicly held corporation. This is a company with its ownership shares traded on a public exchange. The ease of buying and selling shares on a public exchange typically increases the value of the company. Therefore, many investors desire that shares ultimately become publicly traded. A company may start as a sole proprietorship, become an LLC, and then be converted into a corporation with its ownership shares traded on a public stock exchange. In the circumstance where the company is growing, the business structure will change over time.

Another issue is the ability to raise capital through banks or by using the SBA to guarantee a loan through a participating bank. The first step in getting an SBA loan is determining that the “business is officially registered and operates legally.”[13] This means that the borrowing business is a company that is registered in a state to do business. An entrepreneur can borrow up to $4.5 million (the SBA limit[14]) to fund operations. However, the first step is to create a proper business entity to which the bank can loan the money or in which an investor can invest. The typical entities to which banks lend money and investors invest money are partnerships, LLCs, or corporations. To create these entities, an entrepreneur needs to file the appropriate paperwork within a given state.

Business Domicile Considerations

There are multiple reasons why an entrepreneur may consider geographic location when forming and operating a business. Of course, one practical consideration is where the entrepreneur lives, at least in terms of operating a small local or regional business. However, there are other important considerations, such as differing formation/incorporation laws, widely varying levels of regulation, different types of permitting, and other relevant factors. As a rule, a corporation is considered a citizen of both its state of incorporation and the state of its principal place of business.

The state where a person lives is not necessarily the state in which they must form and/or operate the business (i.e., its domicile). Forming a business in the entrepreneur’s home state is generally the easiest way to create the entity. However, some entrepreneurs choose to create their business entity in other states for privacy reasons or for tax savings. For example, some states (e.g., Wyoming, South Dakota) have no corporate income or gross receipts tax at all, whereas others (e.g., California, New York) do. Also, some investors might prefer out-of-state incorporation. That said, the entrepreneur must remember that the corporation will be subject to taxes, filing requirements, and other fees imposed by each state of operation and the state of incorporation.

Some states (e.g., Delaware, Nevada, Wyoming) are particularly popular due to the ease of regulations regarding ownership structure and business-friendly laws. Initial fees are cheap, there are little or no renewal fees, and the states emphasize asset protection. While these states offer good reasons to incorporate, they are not best choice for every business. If a business incorporates in one state but does business primarily in another, it will likely have to pay the second state’s fees and/or taxes as well. Entrepreneurs must consider cost and ease of operations when determining the state in which to create their business entity.

Additional Resources

The Balance, a small business resource website, lists all state government offices in which to file the appropriate paperwork (https://www.thebalancesmb.com/secretary-of-state-websites-1201005).

Seeking Help or Support[15]

You’ve learned about some of the challenges in starting the venture and the types of decisions that the entrepreneurial team must make, as well as the importance of recognizing when you don’t know something or that you have encountered a problem. Facing these issues is easier when you recognize that asking for help should be part of the process. Given the wide range of variables involved in starting a new venture, it’s just not possible for one entrepreneur to have all the answers. Asking for help is an intelligent decision: It’s an action that recognizes the complexity of starting and managing a venture.

Fortunately, there are many types of assistance available in the field of entrepreneurship. One primary source of assistance is the entrepreneurial team’s personal network. These people – which includes spouses/partners, family members, business associates, colleagues, and friends – can provide ideas and knowledge from a variety of perspectives and backgrounds. Connecting and reaching out for help requires both the ability to build relationships and the ability to recognize that seeking help reflects maturity and wisdom. As you tap into your network and seek advice, consider each person from a long-term relationship-building perspective. Consider how you might return the favor at a future time, if asked to help, or provide your expertise back to the people you access for help.

As you work with your network, keep track of the person’s name, your conversation, and any commitments made during the meeting. A commitment might be a follow-up message on how you used the advice or response to the request, or an action that you will perform for someone else. Creating a formal network or contact system helps in developing this network into a long-term relationship-based perspective.

When seeking advice, be respectful of the other person’s time. This means identifying exactly what type of help you want to request from the person. Are you requesting an introduction to someone else within that person’s network, or advice about solving a problem, or access to physical resources? Setting up an appointment demonstrates respect, as does preparing for the meeting and explaining how you will use the advice. Remember to thank the person and follow up with feedback on what happened from using the advice. The types of assistance that can be provided through networking include:

- advice or information

- access to other people’s networks

- access to financial resources

- business services such as legal, accounting, or administrative support

- physical resources such as land, buildings, or equipment.

Other free sources of support are instructors of your business courses, other business owners, organizations such as the SCORE (originally called the Service Corps of Retired Executives) and resources within the Small Business Administration (SBA). SCORE – an organization with a network of volunteers across the U.S. and a resource partner with the SBA – offers mentor consultants, workshops, and other assistance to support the success of small businesses. The SBA is a federally funded organization charged with assisting small businesses from startup through their continued existence. The SBA can help with reviewing and improving your business plan, providing assistance in finding funding through loans or grants, and acting as a consultant throughout the venture’s existence. The SBA also provides help in complying with both state and federal regulations. Depending on your business model, you might need licenses or permits, and your local SBA office will be well informed on these topics and can help you acquire the necessary support.

Additionally, there are local, regional, national, and even international groups available to help you navigate the entrepreneurial journey. Most states provide start-up help to small businesses, which can be found by searching the internet for your state’s sponsored help in starting a business. In addition, there are often local meet-up groups and community-supported assistance to help you start your business. You might also find a virtual support group that provides advice from a diverse group of potential business owners.

Pursuing legal assistance can save anguish, time, and money for the entrepreneurial team. In selecting an attorney, look for one with experience in entrepreneurial ventures like yours. Resources to help you find an attorney include checking with your network for a recommendation or contacting the local branch of the American Bar Association. Most states have an online directory of local member attorneys that you can use to search for a lawyer who fits your venture’s needs. Once you have identified an attorney, research the best method for payment of these services. Some possibilities include a monthly retainer fee, payment for specific services, or payment on an hourly basis for work performed.

Other paid services include accounting, tax reporting, and human resource management areas. Opening and managing a business takes time, and assigning a professional accountant the responsibility of preparing monthly financial statements and tax reports can provide you with expert support as well as provide you with time necessary to position your venture into a successful growing business, as does outsourcing personnel tasks such as processing payroll. These supporting companies can be either virtual companies, or a local business, depending on your needs. Especially for payroll and other human resource activities, virtual companies specialize in meeting the administrative needs in a fast and efficient manner. Oftentimes outsourcing administrative areas is a more accurate and cost-effective than completing these tasks within the venture. Although these services cost money, these activities performed require knowledge of laws and regulations that many business owners are not equipped to be experts in, nor can they reasonably stay on top of frequent changes in these matters. This can result in legal problems, as federal and state laws and regulations must be followed.

Some entrepreneurs may seek to work with a local incubator. An incubator typically provides a physical location to work as well as the opportunity for interactions with other new startup owners and teams. The opportunity to be in a shared space with other inspired entrepreneurs can create excitement, sharing of ideas, and opportunities to talk through challenges. Potentially, there could be synergies between your venture and another venture realized through these discussions. Oftentimes, incubators are sponsored by a municipality or government source. These incubators may be unique to the particular community’s interests and available resources.

As you build your support group, you might want to consider creating an advisory group, which is a formal group of people who provide you with advice. In building your advisory group, select people who demonstrate an interest in your venture and your startup team. You want resources who have expertise related to your industry, your target market, and/or your business model. You also want a diverse group of people who can provide insights that reflect different backgrounds and knowledge. This diversity of experience and knowledge provides you with the greatest breadth of advice.

Taking the time to evaluate and deeply think about the decision at hand, the advice you have received, and possible solutions is an important part of decision making. Just as important are pausing and taking time to select a decision that is not reactive and that you feel comfortable with, keeping in mind that your decision might not align with the advice your received. As the lead entrepreneur whose goal is the success of the venture, you are ultimately responsible for the decision. If the advice provided doesn’t feel right, make the decision that does feel right, and make sure you communicate that decision with your team.

Exercise: Checklist of Startup Operations Needs[16]

There are various resources available to entrepreneurs starting a new business, such as a step-by-step guide for entrepreneurs, a list of eight steps for entrepreneurs, and the SBA’s list of steps. In addition, Table 13.1 below offers a checklist of operational needs to consider when launching a venture. Review each list and consider critical next steps for your venture.

Table 13.1 Startup Operations Checklist

| □ | Determine the legal organization of your business (e.g., sole proprietorship, partnership, corporation). |

| □ | Decide on a name for your company. The company name becomes its official legal name for federal and state purposes. A corporate name can be anything that is currently not in use by another company. |

| □ | Write and approve articles of incorporation, bylaws, or management agreements. |

| □ | File organizational papers with the secretary of state (SOS) or its corresponding office in the state in which the company is founded. The SOS returns the registration or charter documents to the company. |

| □ | Make cash payments to the company to start a bank account. |

| □ | Obtain a federal employers identification number (FEIN) from the IRS. This is the company’s federal tax number for income and payroll taxes and filings. |

| □ | Obtain a state employer’s identification number from your state’s employment commission. This is the company’s state tax number for filing unemployment and sales tax reports and payments. |

| □ | Secure your phone number, website, email, domain name. Order business cards. |

| □ | Open a bank checking account with the appropriate corporate name, authorized signers on the signature card, and all other documents that your bank requires to open a business account. Order debit cards or credit cards as necessary. Deposit your startup funds. Set up and test your business deposit processes. |

| □ | Both you and your officers and partners sign agreements regarding the business. |

| □ | Buy or lease your office space. Your local or city government will grant you a certificate of occupancy to occupy the building. You may need additional inspections before final approval: building, fire, health, and plumbing. |

| □ | Open utilities, water, electric, gas, garbage, and phone accounts. |

| □ | Post required notices in a prominent place according to regulations, such as near the timeclock, break rooms, front cash register, or other public location. |

| □ | Apply for and post as required your license for business, either by federal, state, county, or municipal government. |

| □ | Apply for and post as required your license and permits for employees or specific types of products or services. |

| □ | Obtain insurance – such as building insurance, liability for business, and worker’s insurance. Some states allow businesses to exempt themselves from workers’ compensation with proper notice to employees. |

| □ | Order and install furniture, office equipment, shelving, and so on. |

| □ | Order inventory and make product list with pricing, price sheets, or menu boards. |

| □ | Recruit and hire your employees. Training and certification may be required for specific functions such as bartenders, cooks, drivers, forklift operators, or first aid personnel. Be sure employees’ training in specific job functions is completed before opening. The first day of operations is typically a low-key event to ensure that everything is working as planned and that your staff know their roles and responsibilities. This gives you time to correct any weaknesses or shortcomings before the public is aware that your business is open. |

Chapter 13 References

[1] This section is derivative of Entrepreneurship by Michael Laverty & Chris Littel, CC licensed by OpenStax, Section 15.1 (Launching Your Venture).

[2] Glassdoor Team. “How Long Should the Interview Process Take?” June 18, 2015. https://www.glassdoor.com/blog/long-interview-process/

[3] This section is derivative of Entrepreneurship by Michael Laverty & Chris Littel, CC licensed by OpenStax, Section 15.2 (Making Difficult Business Decisions in Response to Challenges).

[4] This section is derivative of Entrepreneurship by Michael Laverty & Chris Littel, CC licensed by OpenStax, Chapter 13 (Business Structure Options: Legal, Tax, and Risk Issues).

[5] International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL). “What Is the Difference between ‘Non-Profit’ and ‘Not-for-Profit’?” 2013. http://www.icnl.org/contact/faq/index.html#difference

[6] Morris, Nichols, Arsht, and Tunnel. The Public Benefit Corporation Guidebook. n.d. http://news.mnat.com/rv/ff00272e4c8b3699806e25d24c48a286df5bf926

[7] Certified B Corporations. n.d. https://bcorporation.net/

[8] Certified B Corporations. n.d. https://bcorporation.net/

[9] Tax Foundation. “State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2019.” 2019. https://taxfoundation.org/state-corporate-rates-brackets-2019/

[10] US Internal Revenue Code of 1986. 131 Stat. 2054.

[11] Scott A. Hodge. “The U.S. Has More Individually Owned Businesses Than Corporations.” Tax Foundation. January 13, 2014. https://taxfoundation.org/us-has-more-individually-owned-businesses-corporations/

[12] Scott A. Hodge. “The U.S. Has More Individually Owned Businesses Than Corporations.” Tax Foundation. January 13, 2014. https://taxfoundation.org/us-has-more-individually-owned-businesses-corporations/

[13] U.S. Small Business Administration. “Funding Programs.” n.d. https://www.sba.gov/funding-programs/loans

[14] U.S. Small Business Administration. “Loan Fact Sheet: The SBA Loan Guarantee Program: How It Works.” October 2011. https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/SDOLoanFactSheet_Oct_2011.pdf

[15] This section is derivative of Entrepreneurship by Michael Laverty & Chris Littel, CC licensed by OpenStax, Section 15.3 (Seeking Help or Support).

[16] This section is derivative of Entrepreneurship by Michael Laverty & Chris Littel, CC licensed by OpenStax, Section 12.3 (Designing a Startup Operational Plan).