12 Chapter 12: Pitching Your Idea

Chapter 12 Introduction

The popular reality TV show about entrepreneurs making pitches, Shark Tank, is sometimes erroneously described as a show about pitching. This is false. Shark Tank is a show about people, usually inventors, with interesting back stories who are now looking for help getting their product to its next step. The show offers them the opportunity to pitch their idea to a panel of investors who, if they like the idea, make a financial offer in return to help get the product to market. Every pitch is preceded with what reality TV producers deem to be the more interesting narrative—the entrepreneur’s story. Viewers learn what inspires entrepreneurs, how hard they have worked on their prototypes and pitches, and what they have riding on those few minutes in the room with the “sharks.” Only after the entrepreneur’s story is set up do we get to the punch line, so to speak—the five-minute memorized pitch—which, if the entrepreneurs’ ideas seem viable, is followed by further talk about valuation and mentoring.

Shark Tank does not offer a master class in pitching, but it does highlight an important aspect about the practice: Stories matter – to both investors and customers. That’s why it’s important to make sure you develop a compelling pitch to share your story and present your idea to the world.

Telling Your Story

As an entrepreneur, you need to be able to effortlessly discuss your product and its problem-solution narrative, its value proposition, its market niche, and the competition, but in your pitches, you also need to be able to tell your story. Prepare to tell your entrepreneurial story by applying the most universal story format: the fairy tale. Here is a template you can use:

Once upon a time, we had a problem. Then, we thought of the most ingenious solution. We worked really hard and built several versions of the solution until we found The One. This, the innovation you see before you, is The One. We arrived at it through great personal cost, but here it is, and you can own part of it, not just the innovation on the table beside us, but the idea. You can own a sizeable portion of this business and its potential future growth. All you have to do is trust us, and you can be part of the magic. We will deliver this innovation to millions and make their lives better. We’ll grow together and make the world a better place at the same time. Join us. Invest, and live happily ever after.

Of course, the fairy tale format is not a formula for giving a practical, professional pitch, but it can help you put the pieces of your own entrepreneurial journey on paper so you can weave key details into your pitch as it develops.

Once a company grows, its story grows. But the original stories of the founders still play a part. This bigger story is called a corporate narrative. A corporate narrative is not a fairy tale but relays how a successful company grew from something small, perhaps starting in a garage in California, into a powerful firm or corporation serving millions of people. Companies craft narratives, often with several embellishments, for marketing purposes, but they also serve to remind leaders and employees about the vision and dreams the company’s founders once had.

An example of a startup that still inspires many today is the Hewlett-Packard Corporation (HP). Its origins lie in the efforts of Bill Hewlett and David Packard, two Stanford University classmates in the 1930s. Much like members of a garage band, they started their company in a real garage, and the firm has outgrown its humble beginnings many times over.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Stories

The primary advantage of using stories in pitch development is that they are relatable. Stories are how we make sense of our lives, so it’s natural for stories to help others make sense of our new ventures. Stories are useful for transferring concepts with imagery told from a particular point of view.

When making a pitch, it is best not only to convey the value proposition of your product, but also to convey the value in the way that a loyal, enthusiastic consumer of the product (a brand advocate) would see it. Your goals become their goals. For example, Nike’s Air Jordan brand has one of the most powerful advocate communities in the world. They are motivated by stories of being, in some small way, like one of the greatest athletes of all time. Inspired, they not only buy Nike shoes and clothes, they camp out and wait to be a part of the latest release – like people waiting for the next installment of their favorite film on opening night. Using narrative structures to get your pitch points across can inspire potential investors to see and share your vision and goals.

The downside to narrative-based customer development and marketing is that it can lead to a culture of manufactured need. A new form of consumerism, built on what marketers call the “fear of missing out,” is another way of characterizing the euphoria people feel when they are enraptured by a brand. Fear of missing out (FOMO) refers to the sense that we need to keep up with our peers and the personas they represent in social settings, particularly on social media. They can say they were there and that they had the best stuff first. Critics would say that building such a strong identity to a brand, or even material goods, clouds people’s sense of what is really important in life.

Even as you develop skills in pitching products by crafting inspiring narratives, be aware of the ethical implications of your work. You need to learn how to successfully make pitches to grow a brand and a company or nonprofit, but this is not a license to ignore the impacts of your work. Instead, consider this a call to action to balance your entrepreneurial, consumerist pitches and efforts with prosocial ones as well. Across a career, this kind of balance may be achievable, and, for both mass consumer products and purposeful social entrepreneurship efforts, good storytelling will help you achieve your objectives.

There is another type of narrative that can be pernicious – that of the wildly successful entrepreneur who has it all, or that of the entrepreneur as a superhero. Entrepreneurs often do accomplish things that other people only dream about, but many of the most famous ones have anomalous careers marked also by favorable conditions, luck, and hard work. The narrative that matters other than that of your entrepreneurial effort is your own personal one. The same way a successful startup is expected to iterate and overcome failures, so too are you encouraged and expected to persevere after setbacks when it’s reasonable to do so.

Also, be realistic about your own entrepreneurial story. Entrepreneurs who focus too much on their own narrative might miss important market challenges or deep-seated problems with their design or key features. Issues may arise and be ignored, to the peril of the endeavor, if entrepreneurs believe their own stories are a matter of destiny. Ignoring hurdles, failures, and shortcomings within yourself, your value proposition, or your organization can seriously hinder your ability to grow your venture. Your role as a communicator is not to spin a fairy tale yarn and try to live in it. Rather, your role in telling your entrepreneurial story is to demonstrate your capability to overcome challenges and show your capacity for growth as it relates to perseverance, thoughtful inquiry, and providing value and solutions to others.

Developing Pitches for Various Audiences and Goals[1]

Let’s look more closely at how to develop pitches. A pitch is a formal but brief presentation that is delivered (usually) to potential investors in a startup. As such, a pitch is designed to be clear, concise, and compelling around key areas, typically the key problem or unmet need, the market opportunity, the innovative solution, the management plan, the financial needs, and any risks.

You will often need to craft different types of pitches for different audiences. Key audiences include potential investors, social connectors, potential partners, key employee recruits, and the broader community, particularly if one needs to request permits or regulatory concessions. One misconception about pitching is that it is always done to investors who are ready to fork over a few hundred thousand dollars to the team that presents the best idea of the day. While this is, more or less, the premise of Shark Tank, it is not how pitching works for most entrepreneurs.[2] Entrepreneurs may pitch to friends and family as they develop an idea, and, at another time, they may pitch to well-connected entrepreneurs and investors who have little interest in the market sector in question but who can make the right introductions or helpful connections. Entrepreneurs might make pitches in what is known as a pitch competition, hoping for a shot at funding and mentoring. Pitches come in many forms, but underlying them is that to pitch is to ask for something. Table 12.1 provides an overview of different audiences you might pitch to, outlining how the approach and presentation may vary for each.

Table 12.1 Summary of Pitch Scenarios

| Audience | Pitch Length | Pitch Approach | Key Content | Notes |

| Friends and family | Fifteen minutes | Usually verbal with a simple companion one-page handout explaining the concept, value proposition, and funds needed to get the enterprise off the ground | Should cover basic elements of the business model and concept, unmet need, and solution (including if it seems patentable), market and sales potential, and high-level risks | This common pitch can be emotional as founders are appealing to people they know well and are counting on their personal reputation and credibility vs. detailed data to sell the idea |

| Elevator pitch competitions | Two to five minutes | Usually a verbal pitch or single slide summarizing need, solution, market, opportunity | Should cover high-level innovation, value proposition, and a “call to action” to close the audience | Very common at accelerator or incubator events, university entrepreneurship events, etc. Prizes range from free services to $1,000–2,000 |

| Judges for pitch competition | Five to fifteen minutes depending on venue/rules | Varies from basic verbal to deck of one to eight slides, ending with a “call to action”; might require capital needs | Presentation that may include slides and/or video as specified in competition rules | These are very common and help the entrepreneur refine the pitch |

| Early Investors | Ten to twenty minutes, depending on venue/rules | Standup presentation with slides and video or demo of product/service | Presentation that may include slides and/or video; more formal than pitch competitions with a specific “ask” for capital needs and use | Very common with angel investors; often the deck is required to be sent before the event |

| Employees | Ten to twenty minutes | Standup presentation with slides and video or demo of product/service | Major outcome is to inform and inspire; this can be a recurring event and should be informal | Very common in startups; usually monthly until company is profitable |

| Trade groups/associations | Ten to twenty minutes | Standup presentation with slides and video or demo of product/service; may be tailored to the specific group | Major outcome is to inform and connect to other key groups (investors, customers, etc.) | Very common at trade conferences; some have their own pitch competitions |

| Grant-making agencies (such as NIH, NSF) | Ten to twenty minutes if in person but usually embedded in grant application | Usually written but can lead to face-to-face meeting, depending on agency rules | Outcome is to get “scored” to gain grant funding; if not awarded, company can reapply in the next grant cycle | Grants are often technical and usually awarded for research and cannot be used for any commercial activities |

Pitch Audiences

Regardless of to whom you are pitching, you usually need to include references to your problem-solution statement, value proposition, and key features – and how you prioritize that information will change for different audiences. As shown in Table 12.1, once those core sections are covered, your different presentations should be tailored for different ultimate “asks.” The ask in a pitch is the specific amount of money, type of assistance you request, or outcome you are seeking.

Investors

You were introduced to the different types of investors in Chapter 10 (Financing a Startup). How entrepreneurs structure their pitches can vary depending on which type of investors they are targeting. Individual investors want to know about team, product, value proposition, and potential return on investment. Again, angel investors are individuals who use their own money to invest in companies they’re interested in, whereas venture capitalists are investors who pool money from others and use that money to invest in companies.

Pitching to many potential investors without success can be time consuming and disheartening – but regardless it offers an opportunity to receive valuable feedback. If an investor offers suggestions after listening to your pitch, they must at the very least be considered. You will probably not get all the answers you need concerning how to make your venture an immediate success after giving a few pitches to individual investors and pitch competition judges, but if they take the time to offer a constructive critique, consider the pitch development and performance feedback a valuable experience.

Additional Resources

David S. Rose is the author of Angel Investing. Watch David Rose’s TED Talk where he offers advice about how to pitch venture capitalists.

Friends and Family

Imagine asking friends and family for money to keep your startup going after you have maxed out your credit cards and secured a small business loan only to build a prototype and realize you do not have enough funds to get it to market. A common entrepreneurial journey starts with this sort of self-funded effort. Between 50-70% of startup companies in the U.S. self-fund their initial capital needs, from savings, credit cards, or friends and family.[3],[4]

In one sense, you may be perceived as being more trustworthy with this group, with so much riding on the endeavor. Still, you would frame your pitch differently when going to friends and family than you would if preparing for an investor. You would probably make the tone less formal. You would focus on the value proposition and the immediate outcomes of the loan or investment. You would point out tangible deliverables or milestones that this money would help you attain, and you would need to draw a roadmap from this contribution to likely (not just hoped for) revenues if you were to give yourself the best shot at raising money. Asking friends and family for, say, $10,000 might be more stressful to an individual than to ask an investor for ten times that amount. Your friends and family may want to invest in you, but they will also want to make their decision with a tangible narrative in mind. You want to build this narrative so that they can say: “I gave my family member X, so that they can finish building Y, to earn revenues of Z and continue forward with their innovation.”

Potential Employees

Entrepreneurs also pitch to potential employees by focusing on why they are needed to help the team create something innovative and valuable. Once a product is under development, you must pitch to vendors. Prepare to explain the value proposition and key features in detail and explain how the vendor shares in revenues, such as options about accepting equity in part or in lieu of cash payments for services.

Entrepreneurs might also pitch to each other in hopes of building teams. Since most entrepreneurs are familiar with the structure of the pitch, you may be able to streamline proposals and simply state the value proposition and the ask. You will want to mention your team. The level of detail you share about who will work with you and what their contributions will be depends on the level of interest of the potential collaborator or investor. Future employees will likely want to know who they will be working with. Family and friends may not need to know the employment history of team members, but they, like other investors, will expect to know that there is a team capable of continuing to develop the product.

Other Audiences

Other types of audiences include quasi-governmental bodies, individual investors, incubators, trade groups, and competition judges. The motives and interests of these different audiences differ significantly. For example, governments usually care most about creating or retaining jobs in their communities. Advanced competitions and larger investment firms will want to see concrete numbers demonstrating product viability, market relevance, and previous growth. In other words, they will expect to see more details, and they will usually communicate ahead of time their specific interests. That being said, you must network and investigate which elements of your pitch to prioritize based on individual investor or investment firm preferences.

Pitch Goals

Planning a pitch means researching the region, potential investors, and current competitors working in the same or similar marketplaces. A good pitch explains not only what makes the product or service good but what makes a market good. Research markets in addition to the individual investors you would like to target. Angel investors are hard to find, but markets can be thoroughly dissected. Marc Andreessen, cofounder of Andreessen Horowitz, one of the most successful Silicon Valley venture capital firms in existence, once wrote, “In a great market – a market with lots of real potential customers – the market pulls product out of the startup.”[5] This is presented as an answer to a question Andreessen posed to himself: “What correlates the most to success—team, product, or market?” He set up this question as a rhetorical tool to teach entrepreneurs that without a market, you do not have a product no matter how hard you work or how genius your team is.

Investors specialize: Find investors in the right geographic location and find investors who know the market sector. Your goal should be to find mentors who can explain markets to you in significant, accurate ways. If you find a fertile marketplace, you can practice customer development, and learn and iterate your way to success.

Key Elements of the Pitch

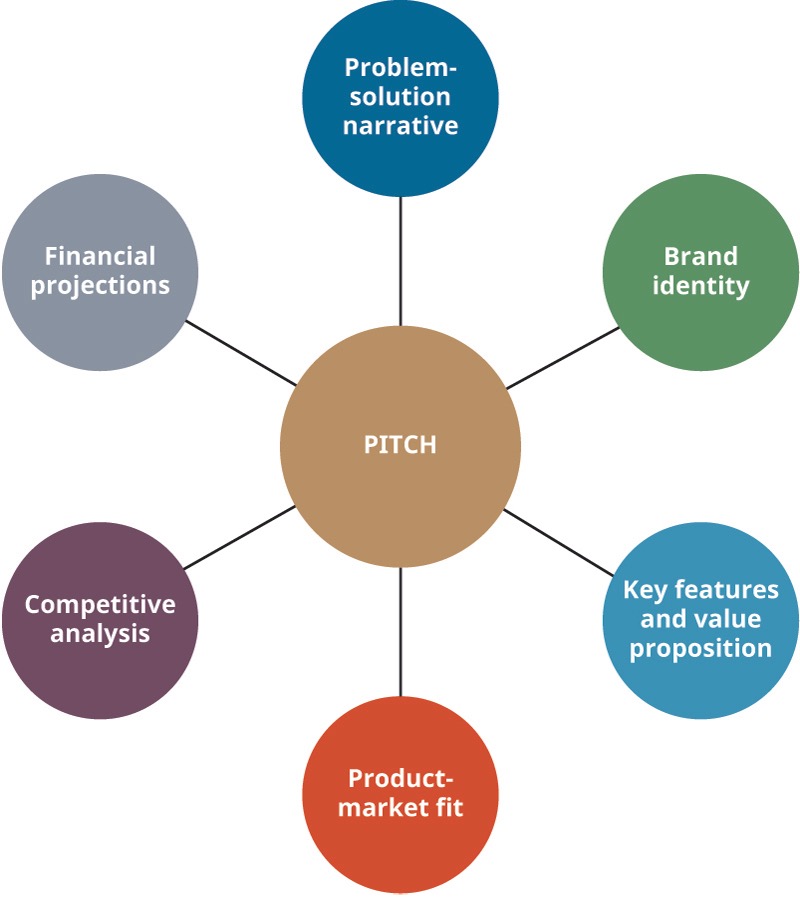

A pitch is usually presented through what is called a pitch deck, alternately called a slide deck. This is a slide presentation that you create using a program such as PowerPoint, Prezi, Keynote, or Google Slides that gives a quick overview of your product and what you’re asking for. As such, a pitch is designed to be clear, concise, and compelling. Below are six key elements of an entrepreneurial pitch to include (see Figure 12.1).[6]

Figure 12.1 Basic Elements of a Pitch

Attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license

- Element 1: Brand identity image and tagline. Your presentation slide deck should begin with a memorable brand image. It can be a logo representing your product in a stylized way, or it could be a screen grab of your product wireframe (a computer rendering if it is a product, and a schematic or flow chart if it is a software/service business model.

- Element 2: Problem-solution narrative. Some entrepreneurial ideas solve common problems. Some solve problems that users didn’t know they had. Communicate the problem-solution narrative succinctly. Incorporate visuals and a “hook” (skit, emotional testimonial, deep question, etc.) to connect directly with the audience. An effective technique when addressing a generally common problem is to ask the question while raising your hand to prompt the audience: “How many of you have experienced this issue/problem/challenge recently?”

- Element 3: Key features and your value proposition. Your pitch can introduce potential investors, collaborators, employees, and others to your key features, your value proposition, and your user interface at the same time. Consider using a mockup of your product or images of a prototype to show your design capabilities while at the same time pointing out key features building to a value proposition. Or if you are a service or nonprofit venture, explain what you plan to provide to individuals or the community.

- Element 4: Product-market fit description. Define the market niche clearly and explain how your innovation serves the market purpose precisely. Not every problem is one people would pay to fix. Explain why there’s a market to overcome this problem, how sizeable it is, and why your value proposition is the best.

- Element 5: Competitive analysis. Demonstrate that your product is unique by defining its competition and illustrating how it will stand out in the marketplace. Investors will pay close attention to any missed or omitted competitors. They will want to see that you can establish barriers to entry, lest some immediate copycat eat up market share. The Entrepreneurial Marketing and Sales chapter covers these concepts as well.

- Element 6: Financial projections. Creating and delivering your value proposition sits at the center of two dynamics: input and output cycles. On the one hand, you must pay for inputs and overhead; but to build a viable business, revenues from outputs, must (eventually) catch up to and surpass expenses. You must show what the overall market is worth (i.e., how big is this pie?) as well as how big your slice (and your investor slice) will be. In many cases, you will want to end with a brief description of your team, demonstrating why you are up for bringing this innovation to the world.

As mapped out here, this could be the basic framework for your pitch deck for a short competition. Some elements can be communicated in a single slide. Some will take more than one. You should flesh out your essential pitch decks with further specifics or with data requested by competition organizers for longer contests. It is suggested that you keep your core deck to no more than ten slides, and that you also practice a two-minute version that covers all six of these concepts quickly, in case you meet an angel investor on the street.

If you have followed this discussion, you have established a vision for your innovation and the company you want to build around it. You have established a mission and identified a clear purpose for it. You should have a keen sense of your entrepreneurial story, but if you cannot express these things in a way that makes other people see the value, your innovation may not survive. You don’t build pitch decks solely for the purpose of asking for money or support. That may be the primary objective, but when you work on your pitch, you build the narrative case again and again for why your idea has value and why other people should buy into your vision.

The Pitch Deck

Pitch decks are the primary means by which entrepreneurs share their vision with the rest of the world. Usually, ten to twenty slides can explain your company, its goals, and key information to persuade an audience to take action (e.g., to invest, to join, etc.). Pitch presentations should be visual and engaging. They should be easy to edit and rearrange, and should engage viewers with art, panache, and reasonable appeals. In general, they communicate the inspiration behind the innovation, its future capabilities, and the strengths of the team. Incorporate visuals to help you tell and clarify your story (i.e., show instead of tell whenever possible), making sure that visuals match your narrative.

As an entrepreneur, you will be judged on your ability to develop and deliver a pitch. It can be taken as shorthand for your ability to research a marketplace, guide a team, and manage a product. Sharing your vision using slideshow software is not easy. Audiences are not easily impressed by status quo pitch presentations, so making an effort to craft a visually appealing can go a long way. At the same time, discerning audiences will be able to quickly notice when a pitch is all flash and no substance. In other words, developing a great-looking pitch deck is important, but it must be built using substantive content.

Additional Resources

Explore a variety of foundational pitch decks, and learn what worked and didn’t with each.

Let’s use an early slide deck from Airbnb as an example. This relatively straightforward deck from 2008–2009 is a popular example because of its simplicity and its powerful value proposition, although some experts note that the design could be better.[7] Nevertheless, this was a successful pitch deck.

This deck was presented after the company grew from its initial seed funding stage into a viable operation with high hopes for future revenue growth. That is, they were already established and making money when this deck was in use. It was presented after the initial investment stage, when the company had done a good deal of customer development. The track record is always in question when small firms go asking for big money, so note how Airbnb describes its previous success and potential for future growth. When funded, “AirBed&Breakfast” would change its name and grow it into a global brand.

- Slide 1: Brand identity for “AirBed&Breakfast” is established, with typeface, use of color, and a clear tagline: “Book rooms with locals, rather than hotels.”

- Slide 2: The problem statement is straightforward: Travelers need an affordable alternative to hotels.

- Slide 3: The solution statement focuses on the nature of the product, that is, that it’s a web platform, and on key features and how they create value, both financial and cultural capital. Note that key features and the value proposition are already addressed through three simple slides.

- Slide 4: To establish product-market fit, you first must have a market. The Airbnb pitch deck notes that at the time there were 630,000 users on couchsurfing.com and 17,000 temporary housing listings on Craigslist in San Francisco and New York combined in one week. Thus, there existed a large potential traveler pool and a large pool of people with rooms for lease, but these groups needed a unified platform.

- Slide 5: The fifth slide details the size of the market and Airbnb’s share, showing potential for growth.

- Slide 6: Completing the case for product-market fit, this slide shows the attractive user interface and provides a mini-narrative for how the product works.

- Slide 7: This slide shows four years’ of revenue totals as simple math: 10 million trips × $20 average fee = about $200 million in revenue. This is evidence of product-market fit and whets the investor’s appetite for potential future earnings.

- Slide 8: This slide shows how Airbnb has already beaten its competition to own the market for certain events and create partnerships.

- Slide 9: Here, investors get the full picture of the competition.

- Slide 10: The financial expectations are relatively well established by this point and were explained verbally. What this shows are the barriers to competition expected to help preserve Airbnb’s position, future earnings, and growth expectations.

Consider what was involved in creating this Airbnb slide deck. The deck is not particularly complicated. AirBed&Breakfast, as it was called at the time, was a market leader in a niche that other companies had previously tried to exploit. The company’s rapid growth was not a guarantee, but for many investors this offer was too good to pass up. Still, at the seed funding stage, some investors did not see the potential in a service that helps people sleep in others’ private residences, and they opted not to invest in Airbnb.[8]

As we have seen, pitch decks and pitches are developed and delivered for various reasons, to various audiences, with varying content. For example, you may prepare pitches to pursue different long-term visions for your product. Or, if you do not secure seed funding, you might scale back your idea, adjust your vision, and rework your pitch. What remains the same is the need to convey how you will bring value to users or customers, and demonstrate the core pitch elements, adjusted for each altered outlook.

Elevator Pitches

It may seem difficult or even impossible to inspire investors via a one- or two-minute elevator speech for a project under development – but preparing for this type of pitch is essential. An elevator pitch is an abbreviated pitch, a memorized talk that can get you in the door to put your full pitch deck on display. The elevator pitch should touch on the key elements of problem-solution, value proposition, product-market fit, and team, and not much else.

Giving an elevator pitch is an art. The elevator pitch can be memorized and should be. It might be delivered informally at networking events or at dinner parties or other social engagements. You never know when you might need to give an elevator speech. You might find yourself talking to someone who’d be interested in your venture, and it might be at a golf outing, on the ski slopes, on the street, in a store, or, yes, in a giant investment firm’s lobby as a courtesy, as in The Big Short. And of course, in elevators. That’s why it should be memorized and up to date.

The classic example of a good elevator pitch is the one job candidates give to land an entry-level job at a company where they have dreamed of working. Adapted from an article in Forbes,[9] here are the key elements of a good elevator pitch for job seekers. First, the pitch must be targeted. It cannot sound as though just any job will do. You need to pitch yourself for the specific role the employer is trying to fill. It helps, second, to write your pitch down, in order to edit and perfect it. Third, it should be focused on the company where you hope to work rather than on yourself. Explain how you understand what they are hiring for and let that be the setup to a story that ends with you being the best person to fit their needs. Fourth, you should clear away the buzzwords and corporate-speak. Finally, practice performing your pitch aloud. Elevator speeches, after all, are given in person.

Additional Resources

NPR’s podcast How I Built This is a compelling collection of first-person accounts by entrepreneurs on all kinds of issues relating to their startups. This episode of “How I Built This” is about Sara Blakely and her elevator pitch for Spanx that turned into a bathroom pitch, and how she seized the moment for success.

A personal pitch is a relatively simple and straightforward task. If you’re asked to write an elevator pitch for your proposed venture, start with about three sentences, or a 280-character tweet. Write it first as a set of talking points so that you don’t get hung up on trying to present the exact words in the exact order. Make your elevator speech broad enough that any member of your team could deliver it and any potential investor could comprehend it in passing. Delivering an elevator speech is a linear process, meaning a person can’t be expected to read back or probe for more information the way they might with a written presentation or in a formal pitch presentation with time for follow-up questions. Be sure to bring business cards and keep your smartphone charged and ready for the exchange of contact information, a sign that you have succeeded in this first step.

Exercise: Developing and Practicing an Elevator Pitch

Part of the idea of an elevator pitch is that you never know when opportunity will strike: when might you have thirty seconds on an elevator with someone interested in supporting your business idea? That’s why thinking through the pitch – including practicing it and getting feedback – can be so valuable.

- Gather a group of 2–3 classmates or entrepreneurially minded friends.

- Have each person spend a few minutes planning a 30-second elevator pitch.

- Take turns pitching your ideas. Take notes on others’ presentations.

- Take turns providing feedback on the pitches. Feedback should focus less on the business idea and more on the presentation of the idea.

Using Feedback to Refine Your Pitch

Pitching requires you to demonstrate that you have assembled a capable, professional team that can turn an idea into an innovation. Users, partners, investors, and others will offer thoughts on how your product or organization should change. Investors consider it a warning sign if an entrepreneur cannot handle feedback.[10] Applying lessons learned from feedback is the purpose of business learning.

Entrepreneurial ventures often start out as problems with no easy solutions. Your initial idea involves your best guess at what an innovative solution will be, but that will evolve more quickly toward product-market fit if your response to feedback is to accept it with grace. Your pitch must demonstrate that you have a great product, that you have done your research, and that you are able to take feedback and apply it to your products to make them better.[11] In other words, you must show you are coachable.

Your venture’s development depends on gathering data to find out what customers like and what investors are willing to fund, so you must seek out positive feedback and build on it. That said, you must also think critically about the positive messages you receive. Are consumers or users enthusiastic in their support or merely polite? This can especially be a concern when pitching to friends and family. Can you clearly identify why you received positive feedback about certain features and not others?

Be sure to gain feedback on many product variables and work to ensure that you can isolate data points for meaningful analysis. The best feedback includes both quantitative and qualitative responses. Quantitative data relate to numerical measurements, including actual purchase and behavior as well as opinion research about a product (e.g., what consumers like and don’t like). Qualitative data, on the other hand, offer complex information that aims to answer the questions “Why?” and “How?” It is often impossible to tell why people do what they do with your product unless you ask them.

In the short term, you can use feedback to decide which features to focus on early in the venture. Many entrepreneurs are faced with the dilemma of having too many good ideas.[12] If you pursue all your good ideas at the same time, your organization can quickly run out of resources. You must focus first on the features that are most popular and relatively affordable to produce and deliver. Those high-return products, services, or features might not be what you use to define your brand in later years, but they can sustain a startup long enough to develop more elaborate products and features that require more time and investment. Over the long term, feedback helps you direct your company toward viability.

Feedback may also come from employees, market leaders, and your competition. Feedback from these sources may be more useful for guiding long-term growth projects. In this sense, feedback means more than advice or product ratings. It can mean tactical moves in the marketplace. Your competitors offer you feedback when they take actions in a marketplace in response to your actions. Be sure to attend to competitors’ actions with the same open mind and the same air of thoughtful skepticism you apply to other forms of feedback.

Once you have the chance to pitch your idea, the next step is carefully measuring quantitative and qualitative feedback about the presentation, mockup, poster, or prototype that approximates what the tangible finished product might look and feel like. Data from pitch competitions are sometimes out of your control, so it may be preferable to incorporate the learning you get from pitch feedback into this customer development process.

Public Speaking and Presentations[13]

Public speaking – giving an oral presentation before another group of people – is a special form of interaction that is common in both higher education and entrepreneurship. You will likely be asked to give a presentation in one of your classes at some point, and your future career may also involve public speaking. Thus, it’s important to develop skills for this form of communication.

Public speaking is like participating in class – you have the opportunity to share your thoughts, ideas, and questions with others in the group. In other ways, however, public speaking is very different. For starters, you must stand in front of your audience to speak – and for most people, that changes the psychology of the situation. You also have additional time to prepare your presentation, allowing you to plan it carefully – and, for many, giving more time to worry about it and experience even more anxiety!

Overcoming Anxiety

Glossophobia, or the fear of public speaking, affects many individuals. Though a few people seem to be natural public speakers, most of us feel some stage fright or anxiety about having to speak to a group, at least at first. This is completely normal. We feel like everyone is staring at us and seeing our every flaw, and we’re sure we’ll forget what we want to say or mess up. Take comfort from knowing that almost everyone else dreads giving presentations the same way you do! But you can learn to overcome your anxiety and prepare in a way that not only safely gets you through the experience but also leads to a successful presentation. Here are some proven strategies for overcoming anxiety when speaking in public:

- Understand the anxiety.Since stage fright is normal, don’t try to deny that you’re feeling anxious. A little anxiety can help motivate you to prepare and do your best. Accept this aspect of the process and work to overcome it. Anxiety is usually worst just before you begin and but eases up once you’ve begun.

- Understand that your audience actually wants you to succeed.They’re not looking for faults or hoping you’ll fail. Your audience is on your side and is not your enemy. They likely won’t even see your anxiety.

- Reduce anxiety by preparing and practicing. The more fully you prepare and the more often you practice, the more your anxiety will go away.

- Focus on what you’re saying, not how you’re saying it.Keep in mind that you have ideas to share, and that’s what interests your audience. Don’t obsess about speaking – instead, focus on the content of your presentation. Think, for example, of how easily you share your ideas with a friend or family member, as you naturally speak your mind. The same can work with public speaking, if you focus on the ideas themselves.

- Develop self-confidence.As you prepare, you may want to make notes that you can refer to if needed during the presentation. That said, the more you practice, the more confident you’ll become, and the less likely you’ll be to forget what you want to say.

Developing a Strong Presentation Style[14]

As discussed above, it’s important to have a pitch deck that not only contains substantive content but also is visually appealing. However, giving a great pitch is only partly about your pitch deck – your delivery is also critical!

Since presentation are delivered to the audience “live,” you should review and revise it as a verbal and visual presentation, not as a piece of writing. As part of the “writing” process, give yourself time to practice delivering your presentation out loud with the visuals. This might mean practicing in front of a mirror or asking someone else to listen to your presentation and give you feedback (or both!). Even if you have a solid plan for the presentation, unexpected things will happen when you actually say the words – timing will feel different, you will find transitions that need to be smoothed out, slides will need to be moved. More importantly, you will be better able to reach your audience if you are able to look up from your notes and really talk to them – and this will take practice.

When it comes time to practice delivery, think about what has made a presentation and a presenter more or less effective in your past experiences in the audience. What presenters impressed you? Or bored you? What types of presentation visuals keep your attention? Or are more useful?

One of the keys to an effective presentation is to keep your audience focused on what matters – the information – and to avoid distracting them or losing their attention with things like overly complicated visuals, monotone delivery, or disinterested body language. As a presenter, you must also bring your own energy and show the audience that you are interested in the topic – nothing is more boring than a bored presenter, and if your audience is bored, you will not be successful in delivering your message.

Verbal communication should be clear and easy to listen to; non-verbal communication (or body language) should be natural and not distracting to your audience. Table 12.2 below outlines qualities of both verbal and non-verbal communication that impact presentation style. Use it as a sort of “rubric” as you assess and practice your own presentation skills.

Table 12.2 Aspects of Verbal and Non-Verbal Communication

| Verbal Communication | |

| Volume | Project your voice appropriately for the room. Make sure everyone can hear easily, but avoid yelling or straining your voice. If using a microphone, test it (if possible), check in with your audience, and be willing to adjust. |

| Pace | Don’t rush! Many people speak too quickly when they are nervous. Remind yourself to speak clearly and deliberately, with reasonable pauses between phrases and ideas, and enunciate carefully (especially words or concepts that are new to your audience). |

| Dynamics and tone | Speak with a natural rise and fall in your voice. Monotone speaking is difficult to listen to, but it is easy to do if you’re nervous or reading from a script. Remember that you are speaking to your audience, not at them, and try to use a conversational tone of voice. |

| Filler words | Limit the number of “filler” words in your speech (e.g., ”uh,” “um,” “like,” “you know,” “so,” etc.). These words can creep in and take up space. You may not be able to eliminate them entirely, but with awareness, preparation, and practice, you can keep them from being excessively distracting. |

| Non-verbal Communication | |

| Location | Position yourself where your audience can see you, but do not block their view of the visuals. |

| Eye contact | Look at your audience. This will make them feel as though you’re talking to them. Even if you have notes that you want to reference, you should practice your pitch enough that you do not have to rely heavily on reading from them. |

| Posture | Stand comfortably. Depending on the setting, you might move around during the presentation, but avoid too much swaying or rocking back and forth while standing – stay grounded. |

| Gestures | Use natural, conversational gestures. Avoid nervous fidgeting (e.g., pulling at clothing, playing with a pen, touching face or hair, etc.). |

As you plan and practice a presentation, be aware of time constraints. If you are given a time limit, respect that time limit and plan the right amount of content. As mentioned above, timing must be practiced. Without timing yourself, it’s difficult to know how long a presentation will actually take to deliver.

Finally, remember that presentations are “live”, so you need to stay alert and flexible to deal with the unexpected:

- Check in with your audience.Ask questions to make sure everything is working (“Can everyone hear me?” or “Can you see the screen if I stand here?”) and be willing to adapt to fix any issues.

- Don’t get so locked into a script that you can’t improvise.You might need to respond to a question, take more time to explain a concept if you see that you’re losing your audience, or move through a planned section more quickly for the sake of time. Have a plan and be able to underscore the main purpose and message of your presentation clearly, even if you end up deviating from the plan.

- Expect technical difficulties.Presentation equipment fails all the time – the slide advancer won’t work, your laptop won’t connect to the podium, a video won’t play, etc. Obviously, you should do everything you can to avoid this by checking and planning, but if it does, stay calm, try to fix it, and be willing to adjust your plans. You might need to manually advance slides or speak louder to compensate for a faulty microphone. Also, have multiple ways to access your presentation visuals (e.g., opening Google Slides from another machine or having a flash drive).

Developing Strong Group Presentations

Group presentations come with unique challenges. You might be a confident presenter individually, but as a member of a group, you are dealing with different presentation styles and levels of comfort. Here are some techniques and things to consider to help groups work through the planning and practicing process together:

- Transitions and hand-off points.Be conscious of and plan for smooth transitions between group members as one person takes over the presentation from another. Awkward or abrupt transitions can become distracting for an audience, so help them shift their attention from one speaker to the next. You can acknowledge the person who is speaking next (“I’ll hand it over to Sam who will tell you about the results”) or the person who’s stepping in can acknowledge the previous speaker (“So, I will build on what you just heard and explain our findings in more detail”). Don’t spend too much time on transitions – that can also become distracting. Work to make them smooth and natural.

- Table reads. (Table reads are what actors do with scripts as part of the rehearsal process. When your groups presentation is outlined and written, sit around a table together and talk through the presentation – actually say what you will say during the presentation, but in a more casual way. This will help you check the real timing (keep an eye on the clock) and work through transitions and hand-off points.

- Body language.Remember that you are still part of the presentation even when you’re not speaking. Consider non-verbal communication cues – pay attention to your fellow group members, don’t block the visuals, and look alert and interested.

Engaging your audience

As a last point, you should also consider how you are going to connect with your audience, to get them interested in and excited about your presentation. Here are some strategies that you may want to use in your pitch to better engage your audience.

- Telling a personal story that relates to your topic.

- Comment on a recent event or news.

- Show an interesting visual image.

- Ask a question (rhetorical or show of hands).

- Tell a funny (but related) anecdote or joke.

- Use a unique or interesting prop that is related to the topic.

- Get the audience to do something (a poll, an exercise, a game, etc.).

Chapter 12 References

[1] Portions of the material in this section are based on original work by Mark Poepsel and produced with support from the Rebus Community. The original is freely available under the terms of the CC BY 4.0 license at https://press.rebus.community/media-innovation-and-entrepreneurship/.

[2] Bill Rader. “The Truth about Pitching (and Why Many Entrepreneurs Fail Here).” Inc. November 22, 2017. https://www.inc.com/bill-rader/what-theranoss-downfall-can-teach-entrepreneurs-about-pitching.html

[3] Laura Entis. “Where Startup Funding Really Comes From (Infographic).” Entrepreneur. November 20, 2013. https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/230011

[4] Meredith Wood. “Raising Capital for Startups: 8 Statistics That Will Surprise You.” Fundera. October 23, 2019. https://www.fundera.com/resources/startup-funding-statistics

[5] Marc Andreessen. “Part 4: The Only Thing That Matters.” The PMARCA Guide to Startups. June 25, 2007. https://pmarchive.com/guide_to_startups_part4.html

[6] Mark Poepsel. “Pitching Ideas.” Media Innovation and Entrepreneurship. (Montreal: Rebus Community, Fall 2018). https://press.rebus.community/media-innovation-and-entrepreneurship/chapter/pitching-ideas/. This material is based on original work by Mark Poepsel, and produced with support from the Rebus Community. The original is freely available under the terms of the CC BY 4.0 license.

[7] “Airbnb Pitch Deck.” Slidebean. 2009. https://slidebean.com/blog/startups/airbnb-pitch-deck

[8] Alice Truong. “The Investors Who Passed on Airbnb’s Seed Funding Had Their Reasons.” Quartz. July 13, 2015. https://qz.com/452384/the-investors-who-passed-on-airbnbs-seed-funding-had-their-reasons/

[9] Nancy Collamer. “The Perfect Elevator Pitch to Land a Job.” Forbes. February 4, 2013. https://www.forbes.com/sites/nextavenue/2013/02/04/the-perfect-elevator-pitch-to-land-a-job/#7843035b1b1d

[10] John Rampton. “25 Reasons I Will Not Invest in Your Startup.” Entrepreneur. September 15, 2014. https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/236999.

[11] Michelle Ferrier and Elizabeth Mays. Media Innovation and Entrepreneurship. (Montreal: Rebus Community, Fall 2018). This material is based on original work by Mark Poepsel, and produced with support from the Rebus Community. The original is freely available under the terms of the CC BY 4.0 license at https://press.rebus.community/media-innovation-and-entrepreneurship/.

[12] Mayo Oshin. “5 Things to Do When You Have Too Many Ideas and Never Finish Anything.” n.d. https://mayooshin.com/5-things-to-do-too-many-ideas/

[13] Julie Warkentin. 2023. “Chapter 17: Presentation Skills.” In Writing for Academic and Professional Contexts: An Introduction. CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/comm/chapter/7-4-public-speaking-and-class-presentations-university-success-2nd-edition/.

[14] This section is derived from “Chapter 10. Designing and Delivering Presentations” in Fundamentals of Engineering Technical Communications. CC-BY-NC 4.0, available at https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/feptechcomm/chapter/10-presentations/